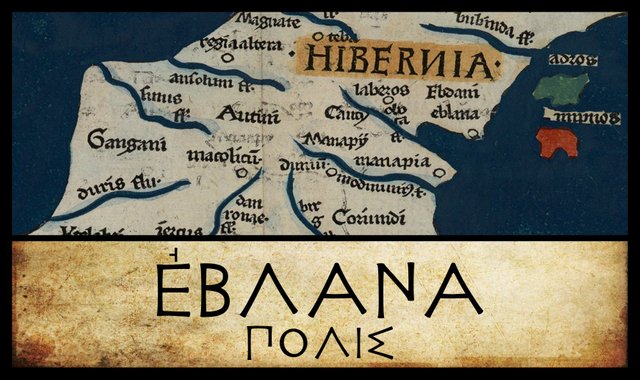

Εβλανα Πολις

The next landmark on our tour of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography of Ireland is Εβλανα Πολις, or Eblana City. Much ink has been spilt in the attempt to identify this toponym, which appears to have left little or no trace in our native records. This coastal settlement was obviously named for the local tribe, the Εβλανιοι [Eblanioi], whose identity is also a matter of speculation. This situation is further complicated by the fact that there are discrepancies between the different manuscripts in both the spelling of the tribal name and the position of the settlement.

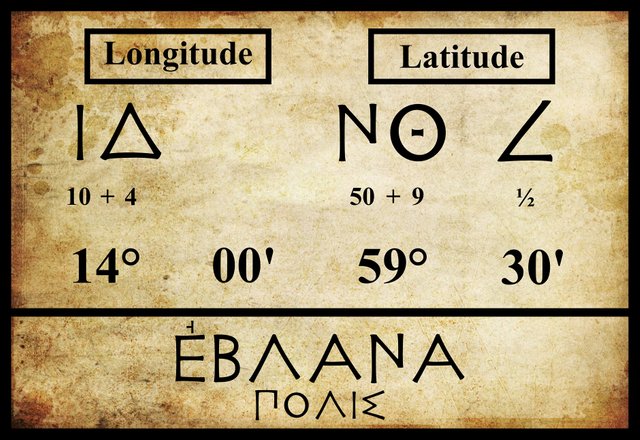

In the previous article in this series, we saw that the three modern editions I have been following—Müller, Wilberg and Nobbe—and the early manuscript source—Vaticanus Graecus 191—are at odds when it comes to the placement of the mouth of the River Oboka. All four agree on the latitude (59° 00'), but Vat Gr 191 places this feature in longitude 13° 20' while the three modern editions place it in longitude 13° 10'. This is not a particularly serious discrepancy: it amounts to about 8 km on the ground, and it does not clash with the location of any other landmark.

A similar discrepancy between the modern editions on the one hand and the Byzantine manuscript tradition on the other also occurs in the case of Eblana. Here, however, the discrepancy is in the latitude and it does clash with another landmark:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 14° 00' | 59° 30' |

| Wilberg | 14° 00' | 59° 30' |

| Nobbe | 14° 00' | 59° 30' |

| Vaticanus Graecus 191 | 14° 00' | 59° 00' |

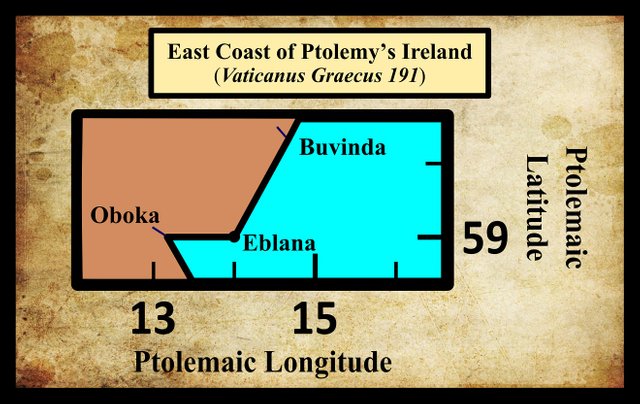

As you can see, all four place Eblana in longitude 14° 00', but there is a difference of half a degree—about 46 km—in the latitude. What’s more, Vat Gr 191 places Eblana in the same latitude as the mouth of the Oboka, but 40'—about 31 km—further to the east.

Among the extant manuscripts, Vat Gr 191 is of the greatest importance for the text of the Geography, because it is the only copy that is uninfluenced by the Byzantine revision (Berggren & Jones 44). Being the earliest surviving source for Ptolemy’s description of Ireland, it is generally considered more reliable than the later manuscripts used by Müller, Wilberg and Nobbe. In this case, however, I believe Vat Gr 191 is at fault. It is hard to see how there could have been a settlement more than 30 km east of the mouth of a river that discharges into the Irish sea:

It may be significant that several manuscript sources of Ptolemy’s Geography call this place Εβλανα, omitting the word πολις [city]. These manuscripts include Vaticanus Graecus 191.

Dublin

Until recently, there was a broad consensus amongst the scholars that Eblana was Dublin. Even today, this claim is routinely repeated. In fact, Eblana is often used as a Classical name for Dublin, in much the same way as America is sometimes called Columbia, or Scotland Caledonia. There are a number of points in favour of this identification:

There is an undoubted similarity in sound and spelling between Eblana and Dublin. Both names contain the grouping -bl-n.

Both are coastal settlements south of the River Boyne.

It is widely accepted that there was a town (Áth Cliath) in the vicinity of Dublin centuries before the Norsemen founded Dublin proper in the 9th century.

Writing in 1745, the antiquarian Walter Harris defended this identity of Eblana and Dublin on linguistic grounds:

Baxter has a Conjecture, not indeed unsatisfactory, that the Word Eblana in Ptolemey has been maimed, and that it ought to be written Deblana, which is a foreign Termination of two British Words, Duv Lhun, i.e. black Water, or black Channel; and corresponds with the Nature of the Bed of this River, which is boggy and black. It is certain antient Geographers have often truncated the initial Letters of Names; as for Pepiacum and Pepidii in Wales, Ptolemey writes Epiacum and Epidii, and Dulcinium, now called Dolcigno in Dalmatia, was called Ulcinium, and Olcinium. (Ware & Harris 39-40).

Here Harris is drawing on the work of the Welsh scholar William Baxter, who made this conjecture in his Latin gazetteer Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum. Modern scholarship, however, does not support Baxter. Ptolemy’s Epiacum and Epidii are now placed in northern England and southwestern Scotland respectively rather than Wales, and they are not thought to have lost any initial consonants (see Roman Era Names and Roman Era Names). As for the Dalmatian city of Ulcinj, it seems to have acquired an initial consonant when it became the Italian Dulcigno. Pliny, however, does record that it was originally named Colchinium before becoming Olcinium (Pliny et al 260). So perhaps there is something to Baxter’s conjecture after all.

The identification of Ptolemy’s Eblana with Dublin has fallen out of favour in recent years, but we have probably not heard the last of it.

Drumanagh

Recently a new identity for Eblana has been found. In the 1950s Roman potsherds were unearthed at Drumanagh, a small peninsula about 20 km north of Dublin (Bateson 70). Exploratory excavations revealed the presence of a promontory fort believed to be of Roman origin, but the site has never been systematically excavated, nor have the recovered artifacts been properly documented. The lack of accurate information, however, has not discouraged widespread speculation. Some historians have theorized that the site may have been a military bridgehead for a planned invasion of Ireland by Agricola, the Roman governor of Britain between 77 and 85 CE. Significantly, however, no Roman weapons were among the artifacts recovered from Drumanagh (Byrne, Daffy 95-99).

Another theory is that the site was a trading emporium with extensive links with Roman Britain. It is not surprising that some researchers wondered whether such a place might not have been Ptolemy’s Eblana:

Εβλανα πολις (Eblana 2,2,8) was a coastal place where people gathered, most likely the promontory fort and harbour at Drumanagh, near Loughshinny, where archaeologists have found traces of a possible Roman trading post. There is no easy explanation of the name Εβλανα. The closest parallel is Ebla, near modern Aleppo in Syria, an important trading post and centre of learning in the Bronze Age. Then various Gaulish names contained a Germanic element *iblio- ‘sparrow-hawk’. And -ebla was a suffix that helped to form the future of a few OI verbs. Or maybe PIE *pelə- ‘to fill’, precursor of OI lán ‘full’, led to a word like Latin populus ‘people’, but Celtic speakers could not pronounce the letter P, and turned it into B, as in Welsh ebol ‘foal’. Most appropriate for a trading place is a precursor of OE gebland ‘mixture’ (literally ‘blended’), with a ge- prefix that readily lost its initial G. Roman Era Names)

There is one major problem with this identification: if the settlement was established during the Roman occupation of Britain (43-410 CE), then it could not possibly have been in existence in 325 BCE, when Ptolemy’s principal source for his Irish geography visited Ireland—according to T F O’Rahilly (39-42). It is quite common for modern commentators and speculators to simply ignore O’Rahilly, who demonstrated beyond dispute that Ptolemy’s Geography describes an Ireland that was about four centuries out of date in Ptolemy’s time. But it is not enough to ignore O’Rahilly : one must also refute him, and this has never been done.

It is possible, however, that the Romans took over an already existent settlement or trading post and fortified it, so the Eblana-Drumanagh identification cannot be dismissed out of hand. In Irish mythology, a character called Forgall Monach is said to have had a stronghold in this region, and the name Drumanagh comes from the Irish Druim Monach, or The Ridge of Monach (O’Rahilly 32-33).

Delvin

Another weakness of the Drumanagh-Eblana identity is the dissimilarity of the names. Recently, however, the local historian Brendan Mathews has suggested that Ptolemy’s Eblana may be related to Ailbine, the old Irish name for the Delvin River. This small stream forms part of the northern boundary of County Dublin and is about 10 km northwest of Drumanagh. Near the mouth of the river is a group of passage graves—pagan Celtic tombs in the Short Chronology—some of which are in the process of being washed away by the encroaching sea.

Metathesis—the tendency to interchange consonants in a word—was rare in Old Irish (Thurneysen §181), so the alteration of Eblana to Ailbine is unlikely, but it cannot be ruled out.

Oenach Descrit Maige—Dundalk

In an earlier article on Manapia, I discussed the possible signification of Ptolemy’s term πολις [city]. There I tentatively accepted the theory that Manapia was a trading emporium in the vicinity of the modern city of Wexford—possibly even the original location of the famous Fair of Carman. Writing in 1919, Eoin MacNeill expressed a similar idea involving the identity of Eblana:

The location which Ptolemy indicates for the Eblani and their city is certainly farther north than Dublin, probably on the coast of Louth. As Ptolemy’s information was derived through traders, it is not unlikely that some of the places which he calls cities were ancient places of assembly. From the poem on the Fair or Assembly of Carman, we know that these were places of resort for traders from the Mediterranean who brought with them “gold and precious cloth” in exchange for products of the country. No doubt they timed their visits for the periodical assemblies, and from the same poem on the Fair of Carman and from other documents we also know that during the time of assembly the place of assembly bore the aspect of a city. In it at those times there was a great concourse of people of all orders; there was a royal court; a kind of parliament; many sorts of public entertainment; and a general market. Somewhere about the middle of County Louth one of these assemblies used to be held. It is called Oenach Descrit Maige “the Assembly of the South of the Plain”—probably the Plain of Muirtheimhne in the district of Dundalk. This place of assembly may have been the city of the Eblani named by Ptolemy, but the name itself has not been traced in Irish writings. (MacNeill 138)

T F O’Rahilly’s contribution to this discussion is relevant here:

Eblani or Ebdani. Ptolemy places these somewhere about the north of Co. Dublin; but they and their town, Eblana, appear to be unknown to Irish tradition. It is, however, just possible (if no more) that a trace of them may exist in Edmann, an unidentified place or district name which is mentioned occasionally in old documents ... From these references we see that Edmann was located between Mag Muirthemne (which covered the greater part of Co. Louth, and extended as far south as the River Dee) and Druimne Breg, the hilly country in the south of Co. Louth; hence it was probably situated near Dunleer ... Now Mid. Ir. Edmann might possibly stand for an earlier *Edban(n), which in turn might stand for *Ebdan, from *Ebodano- or the like. All this, however, is highly conjectural; yet it may give some ground for supposing that the variant Ebdani in Ptolemy’s text is more nearly right than Eblani. (O’Rahilly 7-8)

According to all the editions I consulted, only minor variations in the spelling of Eblana are found in the manuscript sources, all involving Greek accents. As these accents were not in use in Ptolemy’s day, their use is largely irrelevant. But as O’Rahilly notes, there are several variant readings of Ptolemy’s Εβλανιοι [Eblanioi], the local tribe for whom Eblana is named:

| MS or Edition | Spelling |

|---|---|

| Müller | ’Εβλάνιοι |

| Wilberg | ’Εβλάνοι |

| Vat Gr 191 | ’Εβδανοί |

| Parisiensis 1401 | Βλάνοι |

| Nobbe | Βλάνιοι |

The problem with O’Rahilly’s conjecture is that the undeniable similarity between the Ptolemaic letters delta (Δ) and lambda (Λ) can just as easily be invoked to argue that Ptolemy’s lambda was misread as delta, and not the other way round. The fact that the settlement of the Eblani is called Eblana [Εβλανα] in every surviving manuscript—even those in which the tribal name has delta in place of lambda—suggests to me that Eblana is the correct form and that in Ptolemy’s autograph the tribe was called Eblanioi [Εβλανιοι]. It was Ptolemy’s lambda that was misread as delta—not the other way round.

Note that all the locations mentioned by MacNeill and O’Rahilly—Dundalk, Mag Muirthemne, Edmann, Dunleer, Druimne Breg—lie to the north of the Boyne estuary, whereas all extant manuscripts of Ptolemy’s Geography place Eblana south of the Buvinda.

Mag Muirthemne The Plain of the Darkness of the Sea? A coastal plain between the Castletown River and the River Dee. See The Metrical Dindsenchas for the traditional etymology.

Druimne Breg The Ridge of Brega. Brega was a coastal territory between the Liffey and Boyne. Traditionally, the River Boyne marked the boundary between Brega and Ulaid (Ulster), but this was largely a legal fiction. The true boundary was the ridge of hills north of the Boyne between Ardee and Slane. This was Druimne Breg. See Topographic-Map.

| Dublin | Belfast | Oenach Descrit Maige, Dundalk | Drumanagh |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - | - |

| Ware (1654) | - | - | - |

| O’Conor (1766) | - | - | - |

| Lewis (1837) | - | - | - |

| Orpen (1894) | - | - | - |

| Martin (1910) | - | - | - |

| - | - | MacNeill (1919) | - |

| - | Francis (1994) | - | - |

| - | - | - | Bursche and Warner (2000) |

| Stempel (2002) | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | Darcy & Flynn (2008) |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 57

Conclusions

If pressed on the matter, I would say that Ptolemy’s Eblana was a trading emporium on the east coast, somewhere in the vicinity of Drumanagh—if, indeed, it was not Drumanagh itself. But I am reluctant to rule out any of the viable alternatives. I will just say that Louis Francis’s assertion that Eblana could be assigned ... to Belfast is not, in my opinion, a viable alternative.

References

- J D Bateson, Roman Material from Ireland: A Reconsideration, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 73, pp 21-97, Dublin (1973)

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- Seán Daffy, Irish and Roman Relations: A Comparative Analysis of the Evidence for Exchange, Acculturation and Clientship from Southeast Ireland, Ph D Thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway (2013)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Second Edition, Volume 1, S Lewis & Co, London (1840)

- Eoin MacNeill, Phases of Irish History, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1920)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Drumanagh: Imagery ©2018 DigitalGlobe, Map Data ©Google, Fair Use

- Gormanstown Beach: Geograph, © Jonathan Billinger, Creative Commons License

- Passage Tomb at Knocknagin?: © Tom FourWinds, Megalithomania, Fair Use

- Drumanagh at Dusk: Fishing in Loughshinny, © John Cooney, Creative Commons License

good history.I appreciate your blog👌👌

great history.thank you @harlotscurse

informative. @upvote @resteem done bro

nice..informative. keep it up

A very special historical map

Thank you for the great information

You are a really successful person

Dear friend @harlotscurse you wrote well about It is very interesting the theory about the Romans and Britain, I had already read some of that, excellent post.

Excellent story friend Dublin is very beautiful I want to meet her one day thanks for sharing with us your stories are fantastic congratulations

a post of great category, highlighting the history of Ireland and its true origins, you have returned, blessings brother

excellent post,my dear friend @harlotscurse,a post of great category, highlighting the history of Ireland and its true origins, you have returned,thanks for share,

You always share amazing information