POETRY OF ARCHAIC GREECE 1 - Hesiod

Greece’s earliest surviving literacy is poetic; it was the 8th century BC that saw the advent of writing in a form we’d recognise today. An epic was a form of poem common in ancient Greece, and a singer of an epic was a professional oral poet known as an “aoidos”. Aoidoi recited their works from a collection of traditional material, with a common recurring theme of retelling the exploits oh Greek heroes from the past, a past we now know to be the late Mycenaean period of Greece. It doesn’t seem to have been a common trend to make epics based on an earlier or later time period however. The traditions of epic oral recitals seems to have flourished, either entirely or mostly, in Ionia, where the oral poets relied entirely on their own memories to recite these epics, which could often take hours to do, and he also needed to compose as he sung. Common themes and repetitions made in epics were descriptions of objects and scenes like battles, debates, feasts and a sunrise. From talking of these sorts of things, the oralist would have picked up a wide range of vocabulary, making his singing and recitals ever more intriguing.

COMPOSING POETRY

The composition of poems and the handing down of this oral tradition did not require writing. Composition in the epic tradition was a matter of retelling these stories through set phrases, “formulae”, and scenes. Formulae combined an epithet with a noun, introducing characters and/or situations which please the metrical demands of all or part of a hexameter. Set scenes covered the more standard events seen in epic poems, like arming for war, deaths, feasts and sacrifices, and these scenes were often several lines in length. In The Odyssey, Odysseus typically begun his speeches using the phrase “In answer to him [or her], cunning Odysseus replied”, and, a total of 20 times, a new day is introduced by Homer with the phrase “when early-born rosy-fingered dawn appeared”.

EPICS AND THEIR FORMULA

The earliest Greek texts handed down to us come from two Greek oralists from around 700 BC: Homer, who composed “The “Iliad” and “The Odyssey”, and Hesiod, who composed “Theogony” and “Works and Days”. While these epics don’t give us a historical overview of the time period they talk about, they do presuppose ideas onto the listeners of the epics.

Epic formulae tended only to contain one or two epithets to combine with a noun each in a specific metric position; if that given noun were to appear in a part of the line, it was likely to be combined with the epithet. This could tell us that originality to an oral poet would have been a lot harder. But unique lines in Homeric and Hesiodic works far outnumbered repeated lines. Homer’s poems were made largely of big speeches by the main characters, but not all the speakers spoke indistinguishably, and each had their own styles of speaking to distinguish them when the epics were recited orally.

SETS AND MATERIALS

All sets and pieces found in the setting of the epic poems are almost all explicit to the Bronze Age of the Mycenaeans; the world told of in the epics would have been much different and quite unrecognisable to 8th century (and onwards) Greeks. Such items and pieces include the Iliad’s silver-riveted sword, boars’ tusk helmet and the “shield like a tower”, and all these items, and more like them, all seem to fit within the Mycenaean world, or older. These objects commonly carried an entire section of the story narrative with them, and often were preserved due to an episode’s reuse. But, the presence of Bronze Age items does not make the material world the poems depict purely of the Bronze Age.

--

HESIOD'S WORLD

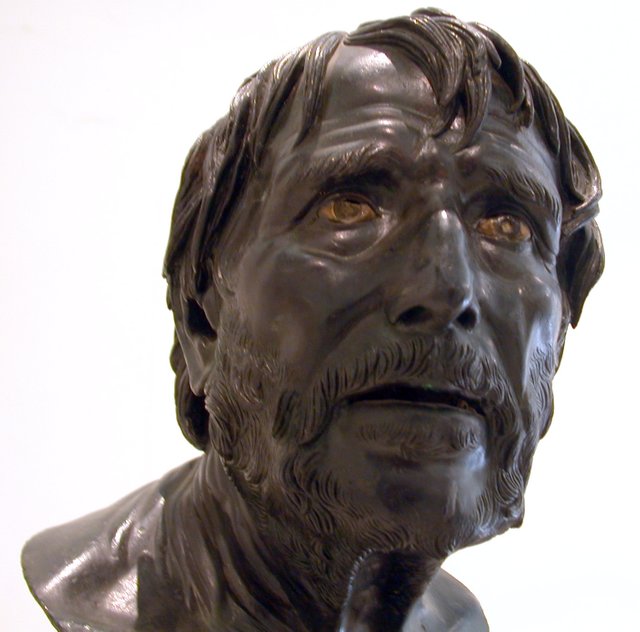

(ABOVE: "Pseudo-Seneca," a bronze bust originally believed to be the Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger, however now thought to be a fictitious bust of Hesiod instead)

Hesiod’s name literally means “he who emits voice”. Two poems of his, among others, survive with us today, and are of great importance: the “Theogony” and the “Works and Days”. Both these poems were originally Hymns: to the Muses in “Theogony” and to Zeus in “Works and Days”; it’s likely right to simply assume that religious festivals were the natural setting for the retelling of these two poems.

THE WORLD OF "THEOGONY"

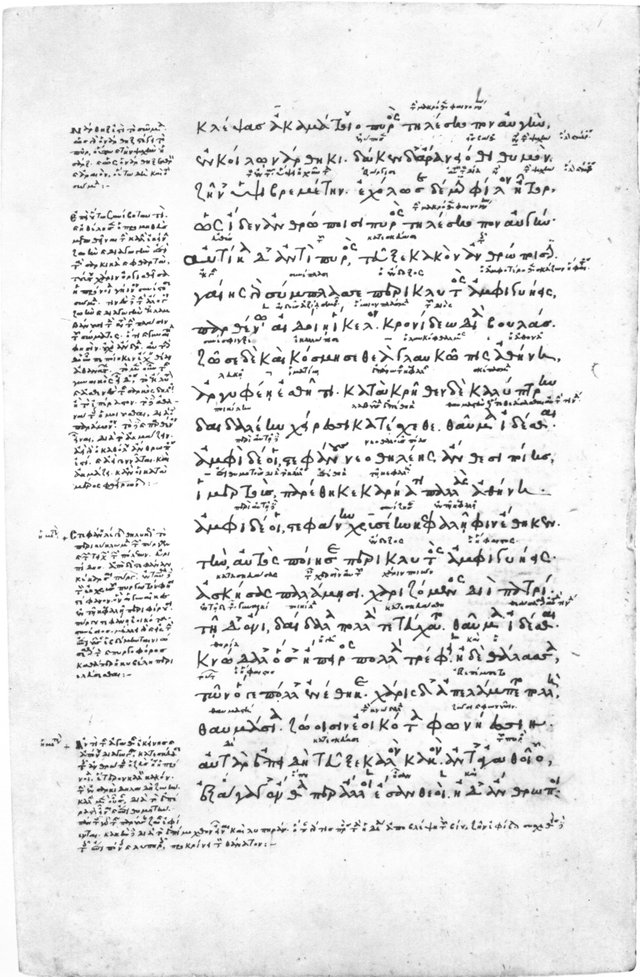

(ABOVE: A 14th century copy of "Theogony" in Greek, with explanatory comments (scholia) written in the margins)

The Theogony retells of the world’s creation, as well as the creation of the gods and their vying for power, and the fight between gods and the Titans. It starts off by the poet introducing the Muses as the ones responsible for singing of the gods, and relating his own encounters with them as he shepherded flocks atop Mount Helikon, and part of the intro briefly celebrates the Muses themselves. While the Theogony retells stories through myth and legend, historians can still draw from key sources of interests:

- Historians can attempt to better understand the world as an orderly creation, and as a place in which they can make sense.

- The Theogony sets moral and immoral, and just and unjust, patterns out.

- It lays out a tradition of thinking about the gods, quite a separation from the Iliad and Odyssey.

(ABOVE: "The Dance of the Muses at Mount Helicon" by Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1807)

(ABOVE: "Hesiod and the Muse" by Gustave Moreau, 1891, now at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

Theogony’s cosmogony prioritises Earth, what lay underneath it (Tartaros) and desire (Eros). These were the first things to have come into existence after chaos, the time before the universe’s existence. Heaven and the Earth’s water were created soon after, and the union of Earth and Heaven lead to the creation of giants, gods and monsters, and it’s these creatures that would struggle for dominance in order to discipline the wilds of the world, so that gods and humanity can live side by side, unequally yet stably.

PROMETHEUS

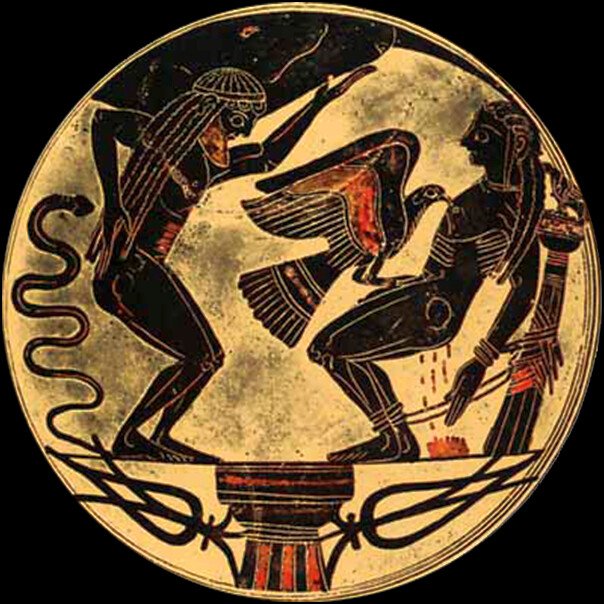

(ABOVE: Spartan pottery showing Prometheus and Atlas taking their punishments, c.550 BC)

Theogony’s most famous way of telling of human and god relations is through Prometheus and the creation of women. Prometheus, whose name means “Forethought”, was one of four children of the Titan Iapetos, the older brother of Kronos and son of Earth and Heaven. His three siblings were Atlas, who was used to hold up the heavens forever with his strength, Menoitios, a violent man who celebrated his strength and who made Zeus use his lightning against, and the witless Epimetheus (meaning “Afterthought”). The wily Prometheus was punished by Zeus after he divided an ox up unequally during the time when humanity’s world and the divine world were now apart. Prometheus’ division of the ox can give us an insight into why Greeks sacrificed ox the way they did: Prometheus’ division gave the gods the bones wrapped in fats, and man received the ox’s flesh. Likewise, in Greek sacrifices, the fat and bones are burnt on the altar as the offering to the gods. Zeus reacts to this by taking fire away from mankind, which Prometheus steals from under him anyway and gives to man. Zeus not only punishes Prometheus for this, but also gets Hephaistos, the god of crafts, to create a woman - Pandora - and loads her with plenty of charm and trouble. Her creation was done to make sure that man labours to support women, so they themselves could have the support they needed in old age. This view sees the relations between humans and the gods as regular and reasoned instead of just arbitrary and random. Fire and meat were seen as gifts from the gods, one which put men in the position which best satisfied the gods and which would ensure that man would pay by their labour for these things in order to support the very family structure that set people apart from beasts.

GODS VERSUS TITANS

(ABOVE: "The Fall of the Titans" by Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, 1596-98)

The sense of the gods world being one directed foremost by justice comes most evidently from the account of the fight between gods and Titans; Titans were portrayed as having been the ones who declared a constant war on Zeus. Titans were confined to Tartaros, the dwelling of Night, Sleep, Death, Hades, the waters of Styx, is shown off in Theogony as what ultimately led to Zeus’s rule over the world, alongside other deities who would have other roles to play, and to which Zeus also married Themis, getting Peace, Justice and Good Order in the process. The power of Zeus is what makes sure that good prevails instead of evil, and that the rulers of men derive their wisdom from them.

COSMOLOGY AND COMPARISONS WITH EASTERN EPICS

Theogony is similar to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey when concerned with divine justice. All three poems have the gods bantering with humans, constantly trick them and decide which man’s morality would be most up for question. A noteworthy instance of that last point is when Poseidon destroys the Phaiakian ship which was carrying Odysseus home from Troy. But Theogony explores a different part of Greek myth: Theogony delves into cosmogony (that is the study of the origins of cosmic-related entities, including the universe itself) and the struggles for dominance in heaven, which has little relevance in Homer’s works and actually resembles the epic works seen at the time in the Near East. Some Eastern epics have actually survived today, near completely too. One that survives today is the beginning of a Hittite epic we don’t know the name of, which looks into the struggle for lordship in heaven, another eastern epic survives on the creations and battles between gods known as the “Enuma Elis” and one more epic from the area delves into the creation of man by the gods to make them Earth’s labourers and the dissatisfaction that the gods had towards the sounds men made, which lead to the gods attempting to drown humanity and ultimately being redeemed by a wise man who built a certain ark to survive this flood, known as “The Atrahasis”. Themes, therefore, can be seem between eastern epics and Hesiod’s work. The parallels of the gods fight for supremacy in heaven in both western and eastern epics both involve the castration of the top god, which leads to other gods being born, one of which is in the belly of the castrator; In Theogony, Kronos castrates Ouranos, Aphrodite is born from Ouranos and Kronos swallows and later regurgitates his own children. Differences do still exist of course though: Theogony’s succession struggle happens between a single family, and in the Hittites “Kingship in Heaven”, two families are struggling for dominance in Heaven.

THE WORLD OF "WORKS AND DAYS"

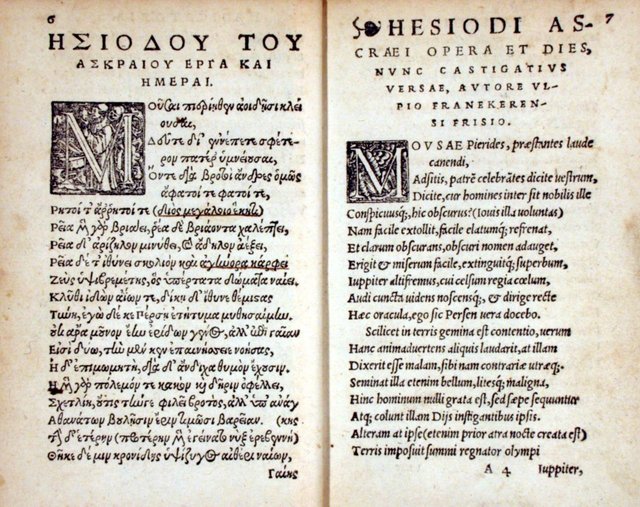

(ABOVE: A printing of "Works and Days" from 1539)

In the Theogony’s introduction, Hesiod introduced himself as he related to how the Muses inspired him. In contrast, the Works and Days poet is present throughout, and while the poem, as a hymn, is directed at Zeus himself, it is, in essence, addressed to Perses, Hesiod’s brother. The two had once had a quarrel over inheritance rights. The direction towards Perses and himself does make Works and Days sound very self-referencing, something very untraditional for an epic of the day, and major parts of the play are of the poets own personal experiences.

Works and Days is made of 3 main sections:

- The poem starts with a celebration to the power of Zeus so as to humble men, which leads the men present to reflect on good and bad strife amongst them, as well as on the injustices of Perses. This is followed by a selection of stories, all of which go someway to explaining why men had to labour in life, and that them failing to do so would have been considered short-sighted as well as predatory on other men.

- A Greek farming year calendar, which also had inscriptions on the occurrence of seasons to help sailors, set out the right way of working, so as to make each harvesting season much more bountiful.

- This section gives miscellaneous advice, some of which is linked to the calendar in the previous section.

Commonly referred to as ‘didactic’ (something that is meant to teach someone something of, mostly, moral value), the teachings of this poem are entirely moral, not practical. In spite of the poems orders of when farmers should plough and sow their farms, as well as the long description of how exactly to construct a plough, it is not farming that can be learnt from Hesiod’s work. A world in which justice rules all can be sensed in Works and Days at a more everyday level, something seen throughout the Theogony too.

THE POLITICAL WORLD OF WORKS AND DAYS

Work and Day’s world is one in which settled disputes lay in the hands of the basileis, (not necessarily hereditary) rulers, an idea supported by “basileis”’s translation of “king”. Hesiod tells of his inheritance argument with his brother Perses as a settled one in Perses’ favour, via Perses bribing other basileis. Hesiod warns of wickedness and judgements made unjustly, claiming these may ruin whole communities, while envisioning no recourse from these decisions, except only through a last divine intervention: “the eye of Zeus sees all”. Hesiod claims clearly that he isn’t in objection with who in particular is in power anywhere. Instead, his concern lies solely with whether decisions made by them are made fairly. He goes as far, in fact, as to say that meetings should only concern one subject, and should not divert onto others in distraction.

Hesiod was born and grew up in the Boeotian town of Askra. He makes it clear that he didn’t wish to pursue a political career of any kind. His Work and Days instead assumes residence within a very political community, which dealt with settling their own disputes. Likewise, Hesiod guesses that people within the community live almost entirely via farming, taking their own livelihoods by themselves, and anyone who failed to do their part for the community would be a huge burden on everyone else. But the purchasing and selling of foreign goods was indeed an option; as Hesiod mentions, it was a good source of profit, but also as blinding to conceive that this would give the community members an easy way out of their own personal hungers and debts. Denial of these sorts of short cuts towards personal prosperity is key to understanding how Hesiod viewed basic fairness in the world, ruined by an uneven inheritance division, a view likely strengthened after the inheritance dispute he went through and lost with his own brother. His assumption is that wealth breeds a lust for power, so it is important for him to stress that one with a lot of wealth should be willing to give rather than receive. While rulers have the power behind them to ruin the good order of resources, it is ultimately wealth, rather than birth rite or position, which Hesiod says gives someone everyday powers over everyone else.

Hesiod’s views on societies and people prospering economically being an important part in the world of politics doesn’t indicate anything to us about his own social class. It’s not evident yet that, although Hesiod shared the idea common in peasant societies of the ‘limited good’, Hesiod thought that prosperity could be achieved at the cost of someone else, instead making note that prosperity itself gives people who have it power over those who do not. Not much can be gained through placing Hesiod in a particular class according to our own modern day standards, as many of the classes present at his time are not in ours, such as in the cases of peasants and independent culture; it’s far better for the reader/listener to note the lack of presence of any social levels below the basileis/king in Hesiod, and the ease of social mobility of which he assumes. This ease of social mobility isn’t just presumed to work by turning poverty into prosperity by work alone, but instead in the way Hesiod’s father is shown as being someone who came directly from poverty while living in Kyme (in Aeolia in north-western Asia Minor), and yet had eventually prospered to the point of being able to leave allotted lands to both of his sons.

WARFARE IN "WORKS AND DAYS"

The world of the time of Works and Days, where morality and logic are very much explored, is a world without much in the way of occurring warfare; the gains and losses that war brings about have a way of disrupting the connection between good labour and resulting prosperity. And if the autobiography of Works and Days is taken as true, the days of Hesiod himself may have been rampaged by warfare; a section of his work is dedicated to his achievement of a “poetic victory” in the funeral games at Chalcis, Euboea, for Amphidamas, and later writers, including Plutarch, have associated Amphidamas and his death with the events surrounding the Lelantine War. The world of the later 5th century BC held onto this war as tradition, for it involved different political communities joining forces on both sides of the conflict, as described by Thucydides.

War in the poem belongs solely to the days of ‘myth of the generations’. Those days, the same era of which Homeric epics were based: Mycenaean Greece) were seen as featuring far more bronze, silver and heroes among a collection of failings that followed a golden race which never had to labour like his own generations did. Within these races successions, Hesiod described and characterises his own generation as one of iron - one not totally stripped of goodness, but still being stripped of its own morality, and one that will meet a future rampant with the sacking of cities. Just how much this sequence of races scheme goes to exploit already set near-eastern literary tropes (from which similar and later examples are preserved) isn’t clear. But, one function of the ‘myth of the races’ for the poet is allowing moral failings to be explored, which go beyond those that can be displayed in Hesiod’s disputes with his brother Perses. The wider view of human nature looked into through this, akin to the dilemma present in the stories of Perseus and Pandora, sets up the full breadth to which the question of the correct relations between the gods and men outlines the conduct of life in the narrower community.

(ABOVE: Zeus prepares Pandora, alongside Hermes, by Josef Abel, 18th-19th century)

--

EXAMPLE TEXTS FROM HESIOD

[Hesiod's "Theogony", 176-92]

“Ouranos (Heaven) came bringing on night, and he embraced Gaia (Earth) desiring to make love, and stretched himself all upon her. But his son from his hiding place stretched out with his left hand and with his right he took the great sickle, long and jagged, and swiftly cut the genitals from his own dear father, and threw them behind him to be carried away. They did not leave his hand without having an effect: all the bloody drops that spurted out Gaia received, and when the seasons of the year had gone round she gave birth to strong spirits of vengeance and great giants, gleaming in armour, with long spears in their hands, and nymphs known throughout the boundless earth as Tree Nymphs. As soon as he had cut off the genitals with the steel he threw them down from the land to the stormy sea, and when they were carried for a long time through the waves white foam appeared from the immortal flesh, and on this a maiden was reared.”

[Kingship in Heaven, Col. 1.18-35, Ancient Near Eastern text relating to the Old Testament]

“Nine in number were the years that Anus was king in Heaven. In the ninth year, Anus gave battle to Kumarbis, and like Alalus [the former king in Heaven, just defeated by Anus] Kumarbis gave battle to Anus. When he could no longer withstand Kumarbis’ eyes, Anus struggled forth from the hands of Kumarbis. He fled, he Anus; like a bird he moved in the sky. After him rushed Kumarbis, seized Anus by the feet and dragged him down from the sky. Kumarbis bit his ‘knees’ and his manhood went down into his inside. When it lodged there, and when Kumarbis had swallowed Anus’ manhood, he rejoiced and laughed. Anus turned back to him, to Kumarbis he began to speak: “You rejoice over your inside, because you have swallowed my manhood. Rejoice not over your inside! In your inside I have planted a heavy burden. First, I have impregnated you with the noble Storm-God; second, I have impregnated you with the river Aranzahas, not to be endured; third, I have impregnated you with the noble Tasmisos. Three dreadful gods have I planted in your belly as seed. You will go and end by striking the rocks of your own mountain with your head.””

[Hesiod, Works and Days, 213-27]

“Perses, pay attention to what is just and do not foster violence. Violence is a bad thing for poor mortals; not even a good man can bear it easily, but it weighs him down and he comes to mischief. Better is the road that goes the other way, to fairness. In the end justice wins out over violence, as the fool discovers by suffering. Oath comes quickly on the heels of crooked judgements. There is a clamour when justice is dragged around, when men who take bribes lead her on and make judgements about what is right with crooked justice. She follows wailing through the city and the haunts of men, clothed in mist, bringing evil to men who drive her out and do not deal straightly with her.”

[Hesiod, Works and Days, 630-40, on sailing, trading and settling abroad]

“You yourself wait until the season for sailing is come and then drag a swift ship down to the sea. Equip it with a well-fitting cargo so as to bring home a profit. That is how my father and yours, poor Perses, used to sail on ships, because he lacked a good livelihood. And once he came even here, he left Kyme in Aiolis and completed a journey over a great stretch of sea in his black ship. He did not flee riches, wealth, and prosperity, but dreadful poverty which Zeus gives to men. He settled down near Helikon, in a wretched village, Askra, bad in winter, awful in summer, and good at no time of the year.”

SOURCES:

• Hesiod's "Theogony" and "Works and Days"

• "The Histories", Herodotus

• "Moralia", Plutarch

• "Texts, Readers and Writers" lectures, Prof. Eleanor Dickey

• "Ideas of Authority", Lynda Prescott and Fiona Richards

• "Early Greece", Oswyn Murray

• "Greece in the Making 1200 - 479 BC", Robin Osborne

YOUTUBE LINKS (I DO NOT own these videos)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

• "Miscellaneous Myths: The Theogony (Greek Creation Myth)"

• "Miscellaneous Myths: Pandora"

• "Miscellaneous Myths: Hermes"