A Visit To History

Talking about historical sites, I know this is not much of a wow buh I was opportune today to visit Mary Slessor's International Foundation site and Memorial Cairn and and here's what I got to learn about this compassionate history maker. After which I took a couple of photos with her statue

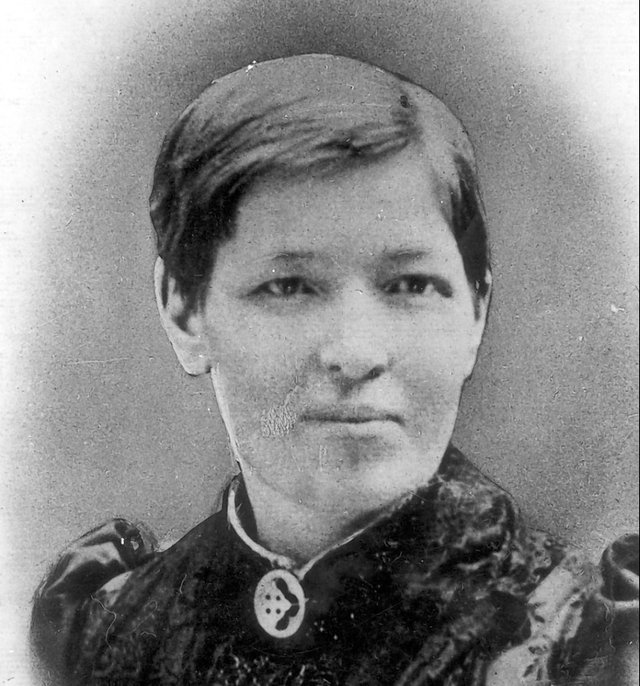

Mary Slessor was born at Aberdeen, Scotland, December 2, 1848. Her father was a shoemaker, but his earnings were usually spent in the taverns. Small domestic possessions were pawned or sold to provide the necessary food and clothing. Mary was the second of seven children. She found her comfort, joy, and strength in God's Word. Bible reading and missionary stories, especially from Africa, captured the interest of both mother and children. They attended Sunday school faithfully and were always present when a missionary was speaking in the church.

LEAVING THE LOOM

At eleven years of age Mary began to work in the spinning and weaving mills, toiling from six to six. When, in the year 1873, the news came from Africa that "Livingstone is dead," Mary was about twenty-five years old. She asked her mother if she might go to Africa as a missionary.

In 1875 she sent her application to the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland, offering herself as a missionary for Calabar. She was accepted on the condition that she take a few brief studies at a normal school in Edinburgh. On the fifth of August, 1876, she sailed for Calabar, Africa.

The first duty of Mary Slessor was to study and learn the trade language called Efik. From her very first contact with the natives her heart was deeply touched because of the cruel treatment they received from their chief. They were whipped, sold, and killed.

Although Mary was not highly trained academically, she had the capacity of an ardent student and a ready learner. She realized that the principal reason for her coming to Africa was to lead people to Christ and train them to continue the work after she was gone. The boys and girls had to be taught to read and write. The abused and mistreated people had to be defended. And Mary had to win the confidence of both the heathen chief and the foreign authority. She knew that she had to live a Christian life as well as preach the truth concerning God and redemption through Christ before the natives would accept her teaching and her Saviour.

SAVING THE LITTLE ONES

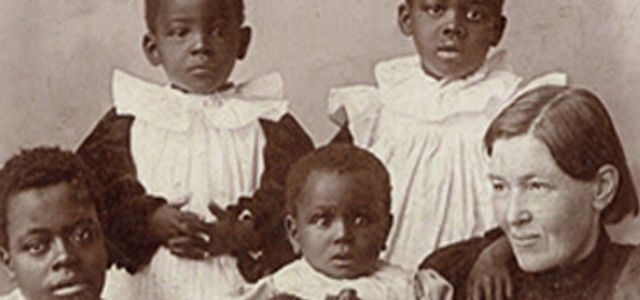

Witchcraft and heathen customs among the people were most difficult to overcome. For instance, the birth of twins meant a triple death—unless Mary Slessor arrived in time to prevent the murder. The mother of the twins was considered to be possessed of an evil spirit and she, together with the twins, would be killed. Mary would plead for the mother and often take the twins to her own humble home. It was her joy to influence the old chief to declare unlawful the murder of twins.

Mary Slessor's great desire in her missionary work was to go to "the regions beyond" to preach and live the gospel of Christ where messengers of the Cross had not been, and to render a service for Christ which up to that time had not been attempted. On her long trips through the jungles and in canoes on the rivers among the cannibals, she was often found barefoot, carrying in her arms twin babies whom she "had rescued from being murdered.

Because of her excellent judgment, her love for the people, and the confidence the High Commissioner of the government had in her opinion, she was asked to sit in their courts. In the district Ibibio she was requested to be in charge of the affairs of the courts, a position she held until November, 1909, when her health did not permit her to continue.

She supervised the construction of humble schoolhouses and churches. On her three brief furlough trips home she not only recuperated physically but was also able to represent effectively the need of the mission field, the claims of Christ, and her need of prayer. She would often repeat, "It is not Mary Slessor, but God and our united prayers that have brought the blessings to Calabar. Christ shall have all the honor and glory for the multitudes saved."

EVERYBODY'S MOTHER

Critically ill with a fever in the early part of January, 1915, she became unconscious. A doctor from the Slessor hospital came to minister to the physical needs of Mary Slessor, but the day for her departure was drawing near. In her dying hour, surrounded by the native Christian girls and women, she was praying in Efik, the language of the people she had served. In the early morning of January 13, 1915, she went to be with the Lord. The natives cried bitterly, "Our mother is dead. Everybody's mother has left us." The coffin was draped with the British flag and brought to Duke Town for burial.