The Fleeting Freedom of the Enslaved: Old New Orleans and the Early Origins of Black American Music

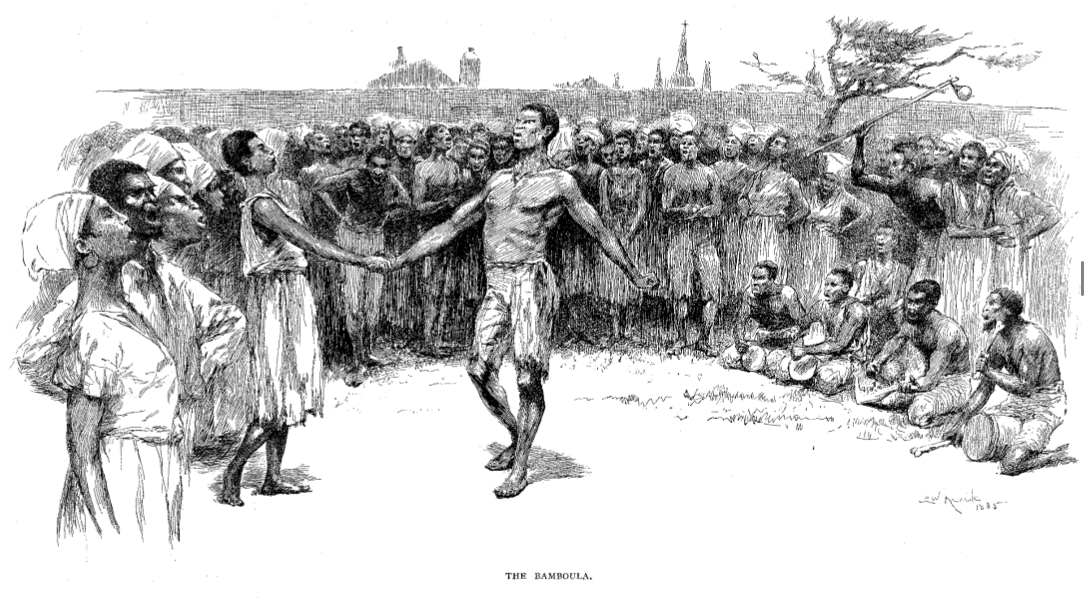

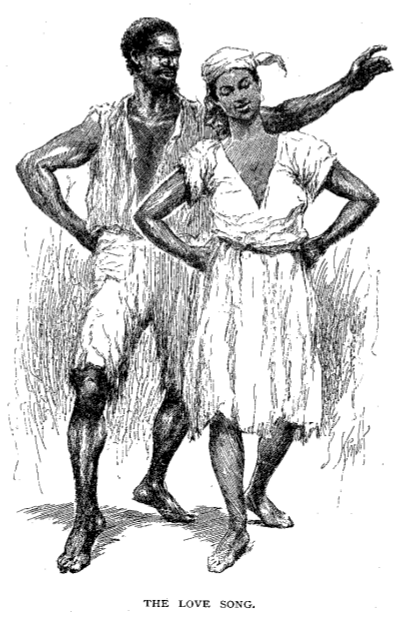

"The Dance in Place Congo”, The Century Magazine, XXXI (February 1886)

The Fleeting Freedom of the Enslaved: Old New Orleans and the Early Origins of Black American Music

Up at the other end of Orleans street, hid only by the old padre’s garden and the cathedral, glistens the ancient Place d ́Armes. In the early days it stood for all that was best; the place for political rallying, the retail quarter of all fine goods and wares, and at sunset and by moonlight the promenade of good society (...).

The Place Congo, at the opposite end of the street, was at the opposite end of everything. One was on the highest ground; the other on the lowest. The one was the rendezvous of the rich man, the master, the military officer – of all that went to

make up the ruling class; the other of the butcher and baker, the raftsman, the sailor, the quadroon, the painted girl, and the negro slave. No meaner name could be given to the spot. The negro was the most despised of human creatures and the Congo the plebeian among negroes. The white man’s plaza had the army and navy on its right and left, the court-house, the council-hall and the church at its back, and the world before it. The black’s man was outside the rear gate, the poisonous wilderness on three sides and the proud man’s contumely on its front.GEORGE WASHINGTON CABLE (1844-1926), The Dance in Place Congo”, The Century Magazine, XXXI (February 1886), 518.

The Foundation of Nouveau Orléans

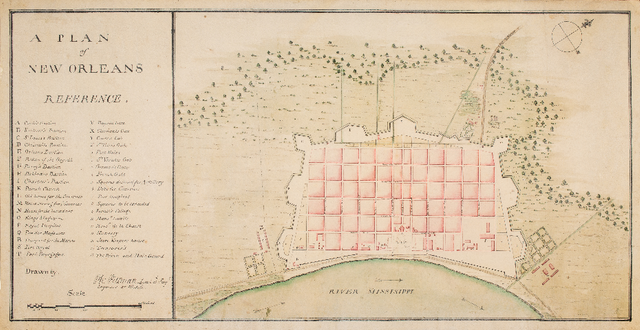

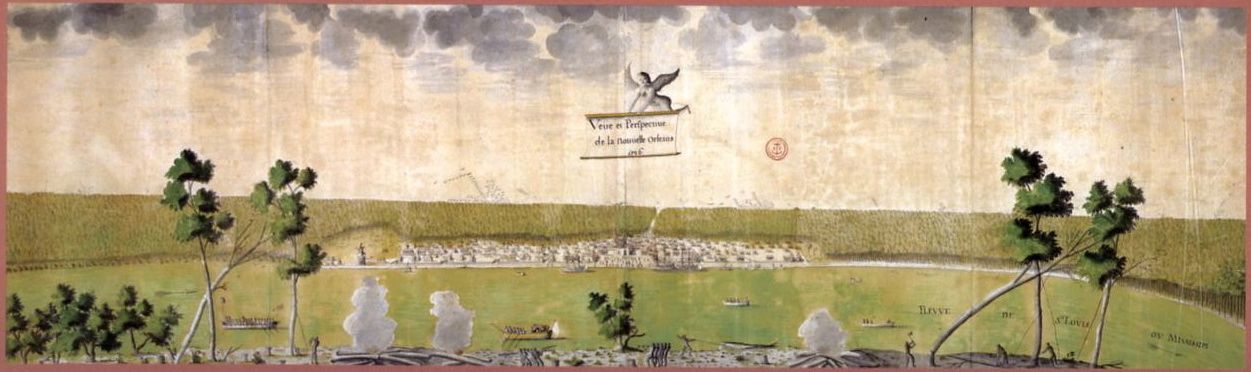

In 1718, the French Mississippi Company decided to establish a new capital for the colony of Louisiana. Built from scratch, New Orleans was meant to revitalize the fledgling and sparsely populated colony and to solidify the French presence in North America. It also represented a political maneuver to confront the threat posed by the British and Spanish empires. More interestingly for our purposes, New Orleans was established as a sort Enlightenment-inspired social experiment, an attempt to design and produce both a rational urban space and an improved, refined society.

The architects and engineers that planned New Orleans had in mind an urban aesthetic that emphasized order and rationality, congruent with the French Enlightenment’s ideals and moral aspirations. They tried to build a ”perfect city”, characterized by regularity, symmetry and clear geometric form. The orderly structure of the urban grid would be matched by a harmonic and hierarchical social organization. 9 In the words of the geographer Peirce Lewis, “the plan represented perfected, purified Europe, ready to be stamped into the soil of the New World wherever the Europeans willed it.”

Philip Pittman, “A Plan of New Orleans.” Watercolor, pen and ink, [1765]. Thomas Gage Papers. Map Division, Maps 8-L-13

The urban project of New Orleans began as an instance of what Lefebvre calls dominated space: an abstract, politically hegemonic, mental design that, through technological means, produced a social space with certain attributes and functions deliberately chosen to satisfy the needs and inclinations of the privileged. However, the reality on the ground did not fit easily with this plan. The domination of space is only one moment in the configuration of space, followed by appropriation. If domination is a kind of objectification of space with a singular purpose, appropriation is conflictive, politically contested, plural. Different social groups try appropriate space for different purposes. Moreover, the natural environment poses limits to the full domination by abstract space; appropriation represents a way around these limits, through accommodation and creativity, in order to facilitate everyday life. In New Orleans, the result of this process of appropriation of space was a urban landscape and a society very different from the one envisioned in the imperial plans conceived in Versailles.

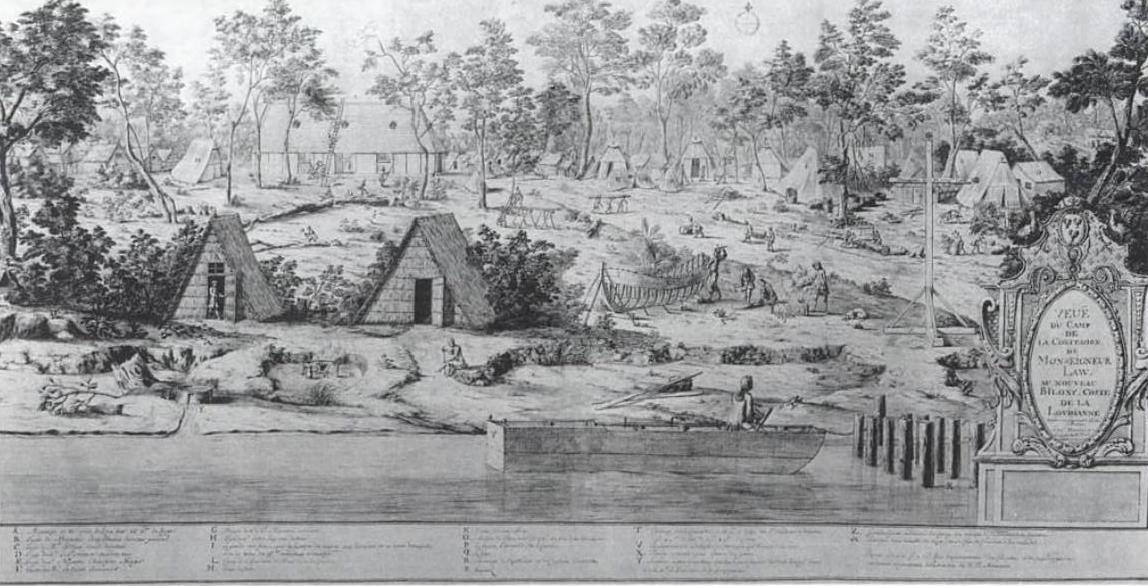

Image of John Law Camp. Source: Africans in Colonial Louisiana By Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, American Council of Learned Societies.

The city soon encountered severe difficulties. “Within ten years of its founding, New Orleans began to appear in literary descriptions as a dark, primitive and abandoned place, governed by immoral pleasures rather than by rationality and law.” During the first two decades the Louisiana colonists faced the chronic threat of famine and starvation. The natural environment of the Lower Mississippi posed daunting challenges for economic development. The domestication of the marshes and wetlands of the region required a great deal of technological expertise and investment. However, the bursting of the so-called Mississippi bubble of the had very detrimental effects for the colony of Louisiana, discouraging potential investors. The stock of the Mississippi company, which had sky-rocketed to ten thousand livres in January 1719, decreased precipitously to 500 livres less than a year later.

The Company was reorganized in 1721, but the support of the Crown for the colony wavered. Overshadowed by the growing plantation economies of Saint Domingue and Martinique, Louisiana was aban- doned by the French metropolitan authorities to its own devices. The survival of New Orleans and its hinterland as a viable social and economic system was only achieved through a complex process of adaptation and creolization. Relying on native knowledge and on the incorporation of African and Indian agricultural techniques, a métis system of rural subsistence came into place, allowing the colony to endure its growing pains.

Maunsel White, Map 1814–1815 New Orleans, 1815. From Library of Congress Map Collections.

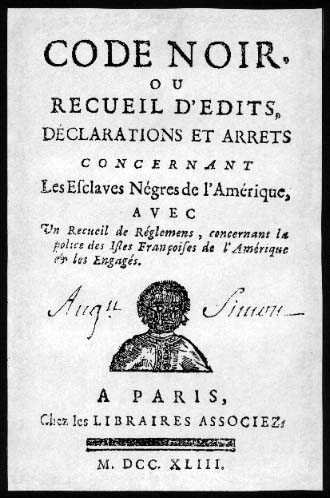

In order to produce export crops like tobacco and sugar, Louisiana planters brought around three thousand slaves during the first 50 years of the colony. The development of a plantation economy was slow and difficult, and the expected profits failed to arrive. The expansion of the slave workforce posed acute financial problems to the owners. In order to assuage this difficulty, individual parcels for cultivation were assigned to the slaves, and they were granted a permission to work part time on their lot. The owners, for once, followed the Code Noir, which established that slaves were exempted from work on Sundays.

Code Noir ou Recueil d'Edits, Déclarations et Arrêts concernant Les Esclaves Nègres de l'Amérique, Avec Un recueil de Réglements, concernant la police des Isles Françoises de l'Amérique et les Engagés, A paris, Chez les Libraires Associez, édité en 1743.

These measure allowed the slaves to achieve a certain degree of self-sufficiency. Now they were able to grow their own food and hunt and fish in the surrounding marshes. They could also earn wages and sell some of the surplus they produce. This practice, which resulted from a forced accommodation to the environmental and economic challenges that New Orleans faced in its early years, had important social and cultural repercussions. The roots of the Congo Square and the cultural expres- sions that were associated with it are tied to the emergence of a thriving slave commercial economy.

Congo Square: market and festival

From about 1750, the enslaved populationn established a weekly market in what would later become Congo Square. They spread their goods on a field outside the city’s rudimentary fortifications, at the end of Orleans Street. This open field, surrounded by wilderness, was never included in the urban planning of the city; it grew out spontaneously in the back of the town out of the commercial entrepreneurship of the slave population.

In the context of the French and Indian War between Great Britain and France (1754-1763), the French authorities decided the reinforce the defenses of New Or- leans. For the first time in its history, New Orleans was enclosed by a proper wall, with an adjacent moot. The perimeter of defense was increased and three bastions were erected. The Place des negres was now within the city walls, situated between the Bastion Orleans and a new street along the old line of fortifications called Rampart. Despite this reorganization of the physical layout of the city, the weekly market and festival continued undisturbed. The Seven Years war ended with a resounding victory for Britain, and French colonial aspirations in the New World took a decisive blow.

"Veüe et Perspective de la Nouvelle Orleans" (View & Perspective of New Orleans), 1726. Ink and watercolor by Jean-Pierre Lassus.

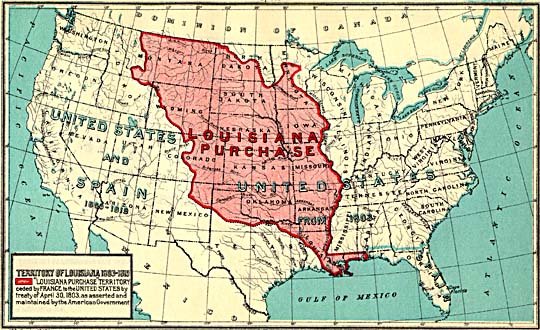

The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763, resulted in the expulsion of France from North America. Canada was incorporated into Britain’s colonial possessions, and Louisiana was ceded to Spain as compen- sation for the loss of Florida to the English. Spanish rule over New Orleans did not fundamentally change the activities carried out in Congo Square. However, from 1769 to 1803 New Orleans experienced a period of remarkable growth, economically and demographically. The city also underwent deeper integration with the commercial circuits of the Atlantic world. A bigger and more robust economy needed a larger slave workforce, and the African population of New Orleans became more ethnically diverse. Moreover, the city absorbed cultural influences from the Spanish Caribbean, especially from Cuba.

In 1803, as part of the Louisiana purchase, New Orleans became part of the United States. The biggest change in the built form of the city resulting from this event was the removal of New Orleans’s old fortifications, reinforced by the Span- ish governor in 1793. The area surrounding Congo Square, were the defensive complex stood, was parceled and subdivided. New streets were cut, but Congo Square was preserved as a public common and continued to hold the weekly mar- ket. Unlike other squares in the city, this site was not beautified: “The city fathers designated it Place Publique and left it a simple, open, grassy plain.” 19 The zone stretching back from Congo Square became the famous Faubourg Treme, possibly the most important American neighborhood during the 20th century in terms of musical creation.

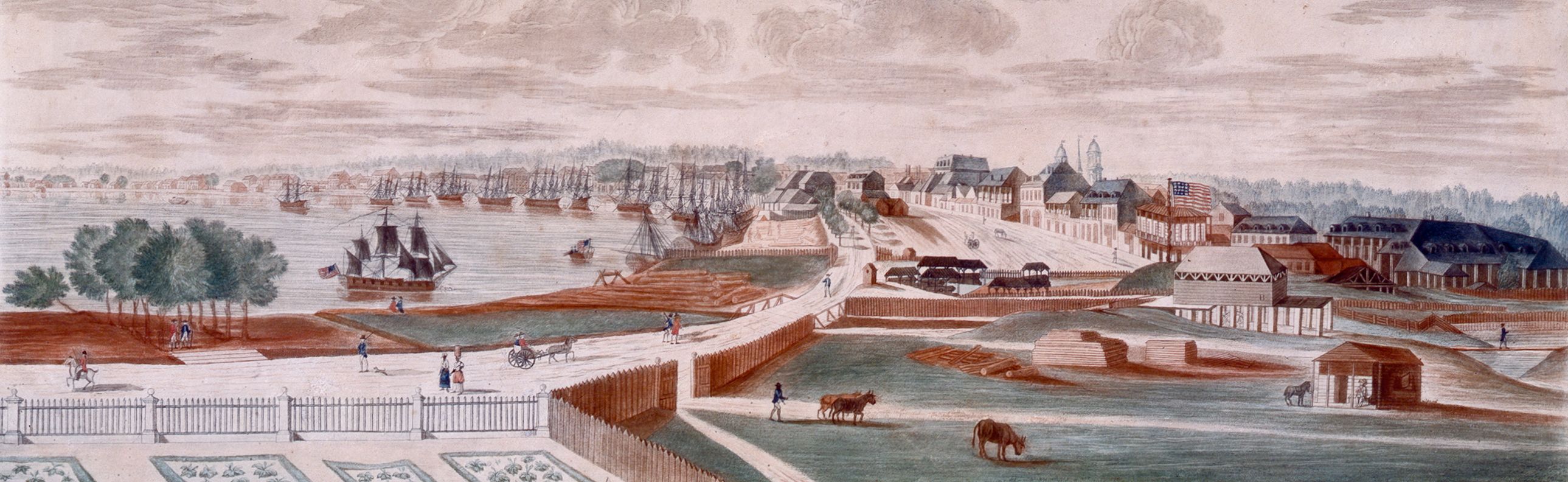

"Under My Wings Every Thing Prospers" by New Orleans artist J. L. Bouqueto de Woiseri, to celebrate his pleasure with the Louisiana Purchase and his expectation that economic prosperity would result under U.S. administration.

New Orleans had always been a culturally mixed place, able to absorb differ- ent ethnic groups and create unique blend. In the first decade of the 19th century, the Haitian Revolution displaced hundreds of planters and their slaves; many of them settled in the city. This was encouraged by the municipal government of New Orleans, in order to increase the number of French speakers. Louisiana's integration into the young American Republic provoked further transformation of New Orleans' society: “While the city, during its long colonial history, had accommodated a number of other incoming groups - the Indians, the Africans, some Germans, and a few Spanish - it had never had to deal with anything like the numbers, assertiveness, determination, or sheer foreign- ness represented by the American invasion.”

"New-Orleans (Louisiana)". View of the Mississippi River front of New Orleans in the late 1840s by Henry Lewis

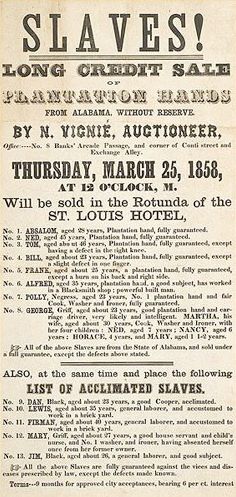

This new influx of inhabitants was composed mainly white protestant European Americans, who had little appreciation for New Orleans peculiarities and traditions. The indignation towards the perceived backwardness and licentious character of the city often focused on the dances of Congo Square. Over the years, a number of urban regulations were enacted to mute the sounds of slave music. In 1837, the city council passed a resolution that authorized “free negroes and slaves to give balls on the Circus Square from 12 o’clock until sunset under surveillance of the police.” In 1845, the conditions were made more stringent: slaves needed to have written authorization by their masters, and the dances were limited to two hours in the afternoon.

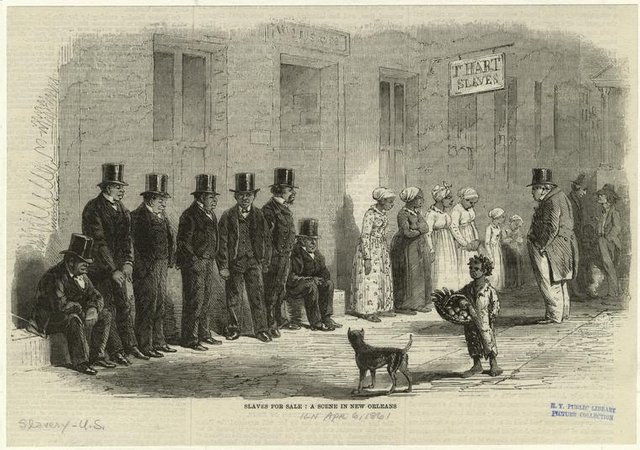

Broadside for 1858 sale of Slaves at the St. Louis Hotel in New Orleans

However, by that time the activities that brought life to Congo Square were diminishing. The old slave market established in the French Colonial period was eclipsed, first by the renovated French Market (1823) and later by the opening of a huge Treme market (1840). The musical life slowly dissi- pated out after the commercial buzz of the square disappeared. “Thus the dancing in Congo Square did not end precipitously, as some writers have supposed, but gradually, crowded out by the physical growth and the Americanization of New Orleans,” Johnson mournfully concludes.

The rhythms of the Other

You can hear ’em in the distance

and the old folks up the bayou say a prayer

that’s when the voodoo people gather

and they play their drums at night in Congo Square.SONNY LANDRETH , lyrics from the song “Congo Square.”

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, a renown architect and engineer who was tasked with the renovation of New Orleans’ waterworks, wrote a journal with his impressions about the city, in which he stayed from 1818 to 1820. His account of the slave gatherings in Congo Square is one of the most detailed (and certainly the most quoted) descriptions of early 19th century African American culture in New Orleans.

Portrait of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. George B. Matthews, after C. W. Peale Oil on canvas, 29-1/2" x 24-1/2" 1931

While strolling around the city one Sunday, Latrobe heard “a most extraordinary noise, I supposed to proceed from some horse Mill, the horses trampling on a wooden floor.” What he found, however, was not a horse mill, but the weekly reunion of New Orleans slave community. And what he mistook for the sound of horses’ hooves was the polyrythmic sounds made by dozens of drums of different kinds. He describes vividly the scene: “They were formed into circular groups, in the midst of four of which, which I examined (but they were more of them) was a ring, the largest not 10 feet in diameter (...). The music consisted of two drums a and a stringed instrument. An old man sat astride of a cylindrical drum about a foot in diameter and beat it with incredible quickness with the edge of his hand and his fingers.” His reaction to the music played could not be more negative: “I have never seen anything more brutally savage, and at the same time dull and stupid than this whole exhibition.”

Not every observer was appalled and disgusted by the dance and music of Congo Square. About forty years later another traveller, James Creecy, found the music and especially the dances fascinating: “In all their movement, gyrations and attitudinizing exhibitions, the most perfect time is kept, making the beats with their feet, heads or hands, or all, as correctly as a well-regulated metronome.” However, both these travelers were onlookers, strangers in the cultural space constituted by African American sounds and ritualistic performance. They entered in a world they could hardly understand. Wether attracted of repulsed, the emotional effects caused on the observers by the particular combination of song, dances and dress that characterized the assemblies at Congo Square had little to do with the way the slaves lived and relished these few hours of freedom.

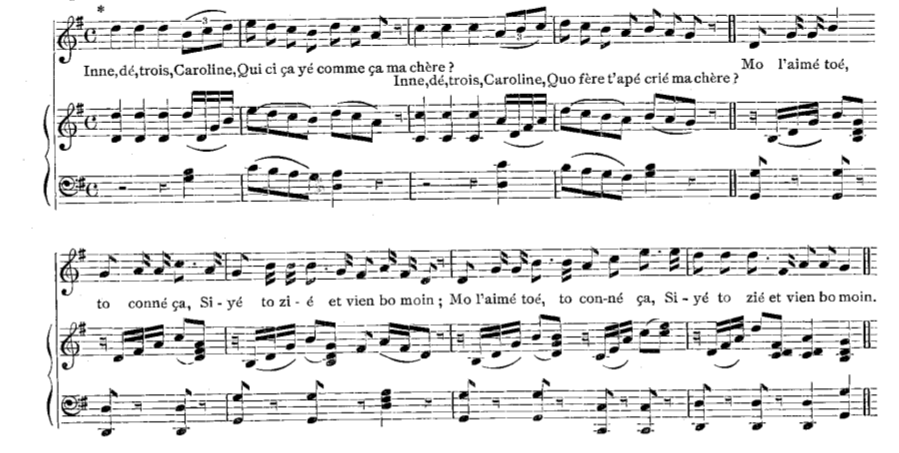

Music notation of Afro-Creole songs, in "The Dance in Place Congo”, The Century Magazine, XXXI (February 1886)

Both Latrobe and Creecy remained outsiders, distant from the meaning expressed by the voices and bodies of New Orleans’ slaves. This puts us at a double distance, as outsiders not just from Congo Square but also from its observers. If the African slaves were the Other in Latrobe’s description, does that mean that Latrobe and us, his readers, are some kind of metaphorical Same? Not at all, in my opinion. Perhaps, the gulf that separates our culture and world-views from that of an American engineer from the beginning of the 19th century is no smaller than the one separating us from the Congo Square dances.

How can we then approach the cultural realm of early Afro-American dance and music? How can we recall through writing, however imperfectly, the signif- icance and symbolic power of Congo Square? This is, at its most basic, the ques- tion that an ethnographic enquiry has to answer. According to Clifford Geertz, the study of culture is always an interpretive endeavor, a quest to find the hidden meaning of human behavior. Culture is symbolic action, a form of communication that tends to be self-enclosing, but is not impenetrable.

In The Sounds of Slavery, a study about the “aural world” of African-American slaves, Shane White and Graham White carve a way into the emotional symbolic content expressed in African American music. Using a broad range of historical sources, musical analysis and different techniques of anthropological interpretation, they paint a vivid picture of slave life in the South of the United States, managing to grasp and convincingly portray the feelings of hope, desperation, terror and occassional joy of the Southern slaves.

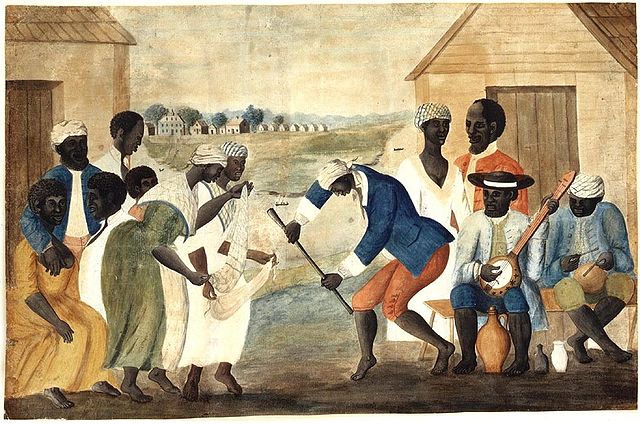

Shane and Graham White point out that the African dancing ring functioned as a symbol of “community, solidarity, affirmation and catharsis.” The brutal experience of slavery broke the ties with many African traditions, but the musical ring was often reenacted at a small scale, renewing temporarily the connections with the past. “In emotional terms, slave calls fleetingly reconstituted the West African ring, the center of communal life and locus of culture-affirming movement and sound.” Nowhere was this more visible than in New Orleans, where hundreds of unsupervised slaves were allowed to reunite every Sunday to carry out a sort of metaphorical abolition of exile.

An important part of this cathartic, reaffirming moment was related to Voodoo rituals. As is well known, Voodoo was a syncretic phenomenon that cannot be equated with the idea of a pure, uncontaminated ’Africanness.’ On the contrary, “Voodoo was created out of a flexible syncretism of a wide variety of beliefs. These do not begin in Africa or Europe and end in New Orleans, but circulate around the Voodoo Atlantic.” Africans brought in bondage to America and their descendants worked as “cultural bricoleurs.” They draw on different traditions to create a “balanced, collectively created whole.” Made up of the scattered pieces of the past, mixed with whatever was available in their everyday life, the culture of Afro-American slaves can be understood, to use Paul Gilroy’s expression, as a “changing, rather than an unchanging same.”

"The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation)" ca. 1785-1795. watercolor on paper, attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, South Carolina. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

The continuity of African American cultural expression despite change and rupture can be appreciated through a comparison of the descriptions written by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and James Creecy. When Latrobe stumbled upon Congo Square, in 1819, most of the instruments he saw were clearly of African design. Many of the slaves had been born in Africa, and some had filed teeth and facial tattoos. Around the middle of the 19th century, when Creecy visited New Orleans, most of the slaves were American-born, and they played “banjos, tomtoms, violins, jawbones, triangles and various other instruments.” European musical forms and instruments were being appropriated by the black community, a process that continued and intensified throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, eventually giving rise to Jazz and Blues.

The music and dances of Congo Square changed greatly from 1750 to 1850, when they began dwindle and shortly after disappeared. However, and despite the impossibility to know with certainty, it seems to me that throughout this century they performed a similar social func- tion: a symbolic reunion with African traditions, but also a communal, syncretic celebration of refashioning in alterity against persisting oppression by the dominant structure.

"Slaves for sale, a scene in New Orleans." 19th century engraving Via New York Public Library Digital Collection. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-409e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99#

Fleeting Freedom

As we have seen, for most of its history Congo Square was a marginalized place, socially and spatially. In the interstices of New Orleans urban structure, the slave community managed to appropriate their own space of cultural expression; to create, to use Foucault’s term, an heterotopia: a place that was, at least once a week, outside the hegemonic configuration of its surrounding.

In Des Espaces Autres, Foucault identifies a series of principles characteristic of heterotopias. The fifth principle explores the “system of opening and closing that both isolates them and make them penetrable.” Foucault describes sites that "seem to be pure and simple openings, but that in fact hide curious exclusions. Everyone can enter into the heterotopic sites, but that is only an illusion- we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded.” This conception of space applies perfectly to the Sunday dances of Congo Square. They were held in an open field accessible to any stroller, but on Sundays, the place became a (culturally) closed environment.

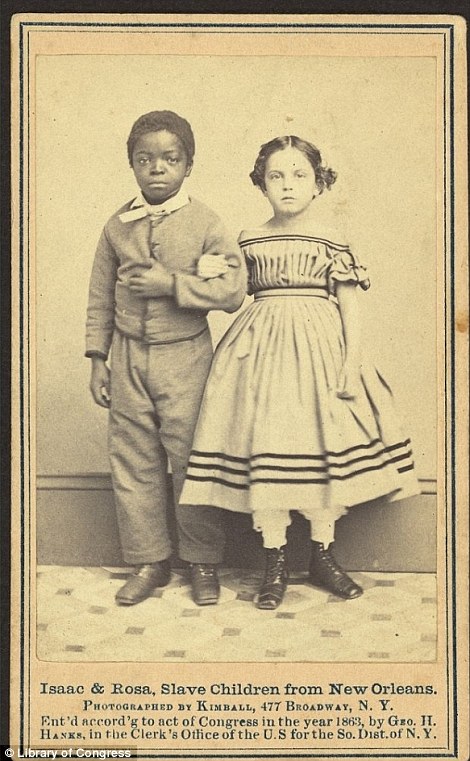

"Isaac & Rosa, slave children from New Orleans," photograph by Kimball, M. H., 1863. From the Gladstone Collection of the Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/2010647842/

The concept of heterotopia bears some resemblance with Lefebvre’s space of representation. It refers, as I pointed out in the introduction, to space imbued with emotion, meaning and imagination, with symbolic connotations grounded on material reality. In Lefebvre’s politics of space, this dimension holds a posi- tive, emancipatory role. 35 Developing an effective opposition to hegemonic class power and bringing about progressive change are fundamentally tied to the cre- ation of alternative spaces of representation, of different ways of living and experiencing space. As Lefebvre says, social space

“contains potentialities - of works and of re-appropriation - existing to begin with in the artistic sphere but responding above all to the demands of a ’body transported’ outside itself in space, a body which by putting up resistance inaugurates the project of a different space, either the space of a counter-culture, or a counter-space in the sense of an utopian alternative to actually existing ’real’ space.”

The space of Congo Square can be viewed through this lens. The festivities held by the African American population every Sunday gave rise to an ephemeral space outside and beyond the material setting and social reality of the urban land- scape. The voodoo rituals, the “complex rhythmic patterns, inflected pitches and timbral diversity” characteristic of African ring circles and the slow crescendo of the dance that finally exploded in a “final frenzy of fantastic leaps in which ec- stasy rises to madness” were deployed to achieve a sort of cyclical if short-lived victory against the body-shackling structures of domination that were that at the core of the institution of slavery.

"The Dance in Place Congo”, The Century Magazine, XXXI (February 1886)

Congo Square was re-appropriated in the sense that it periodically underwent a transformation of its imaginary; an evanescent, non-material redefinition in order “to serve the needs and possibilities of a social group,” the black slaves of New Orleans. Of course, this is only one interpretation among many possible ones, but I think that the re-appropriation of this urban space served to reshape it as a fleeting space of freedom: freedom of the body through dancing, freedom of expression through music.

References

[1] Audubon et al, Louisiana Sojourns: Travelers’ Tales and Literary Journeys (LSU Press, 1998).

[2] Cable, George Washington, “The Dance in Place Congo”, The Century Magazine, XXXI (February 1886).

[3] Dawdy, Shannon Lee, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New

Orleans (Chicago, 2008)

[4] Foucault, Michel, “Of Other Spaces”, in Cauter, Di Lieven, and De

haene, Michiel, Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil So-

ciety (New York, 2008),

[5] Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York, 2000 [1973]).

[6] Gilroy, Paul, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness

(London, 1993).

[7] Johnson, Jerah, “New Orleans’s Congo Square: An Urban Setting

for Early Afro-American Culture Formation”, Louisiana History: The

Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, 32 (1991), 117–157.

[8] Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space (Oxford, 1991 [1974]).

[9] Pile, Steve, Real Cities: Modernity, Space, and the Phantasmagorias of

City Life (London, 2005).

[10] Simonsen, Kirsten, “Bodies, Sensations, Space and Time: The Con-

tribution from Henri Lefebvre”, Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human

Geography, 87 (2005), 1-14.

[11] Sublette, Ned, The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver

to Congo Square (Chicago, 2009).

[12] White, Shane, and White, Graham, The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering

African American History Through Songs, Sermons, and Speech (Boston,

2005).

✅ @sexyhistory, let me be the first to welcome you to Steemit! Congratulations on making your first post!

I gave you a $.05 vote!

Would you be so kind as to follow me back in return?

Congratulations @sexyhistory! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!