Executing Louis XVI

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Executing Louis XVI, King of France

'Portrait of Louis XVI of France', by Antoine-François Callet (1791)

image source

Rightly or wrongly, the decision was made to execute Louis Capet, which was carried out on the 21st of January 1793, in front of a crowd which had once hated the King, but had since grown to pity him and his fate. The decision as to whether or not to put Louis XVI, King of France, on trial for crimes against his country was a matter of great and passionate debate for the members of the Convention. From the time of his arrest in August of 1792 until his trial before the Convention in December that year, the advantages and disadvantages were both debated heavily. On the one hand, he was a King and therefore only answerable to the God who had placed him in such a divine position; on the other hand he was also a citizen of France, and should be tried as one. Once it had been decided that he could, indeed, stand trial as a citizen, he was accused of treason against his country, and by January of 1793 he had almost overwhelmingly been found guilty. The next debatable question was regarding what to do with him next. Would it be better to keep him a prisoner, pardon him, execute him or exile him; what would satisfy the revolutionaries, prevent civil war, and allow for the continuation of the adoption of the republican system. The advantages and disadvantages of each possibility had to be considered most carefully, amongst the volatile and passionate ideals of a country divided between the republican revolutionaries and the royalists.

Robespierre (artist unknown)

image source

‘“Louis must die because the patrie must live,” declared Robespierre in December 1792, establishing the death of the king as the condition for the birth of the Republic.’1 The Jacobins saw the execution as a necessary purging of the old ways, and as a means of cleansing all their social problems. Louis became not only a man who had committed treason, but a symbolic figurehead for a system that was no longer respected in France. ‘He was alternately characterised as monarch, citizen, rebel, alien, tyrant, traitor, and supernatural monster.’2 The Jacobins viewed the king as a divine monarch who had become a monster, and called for justice as the only means to resolving the issue. According to Robespierre, “the salvation of the people, the right to punish the tyrant, and the right to depose him are one and the same.”3 Louis XVI, as a culmination of centuries of monarchical rule in France, was the figurehead who would be used to show the country, both literally and symbolically, that the old institution was dead, and a new one was ready to be ‘birthed’. Kersaint, of the Girondins, tried reasoning. “Citizens, do not believe that your troubles will cease the day you succeed in beheading the king.”4 The Girondins tried to show that Louis was merely a scapegoat, and that the Jacobins were actually planning to takeover the running of the country themselves, and that their ideas on punishment were unnecessarily harsh. Indeed, after the execution of the king there was a swift change in the way justice was meted out to the citizens of France, going from being ‘humane, generous, and merciful’5 to barbarity, cruelty and mercilessness. ‘The dominant principle of the ancien regime was Grace … only God or the monarch had the power to decide who would not be saved … the opposite of Grace was Justice, the fundamental principle of the Revolution …’6 The death of the king began a reign of terror in which thousands of ‘enemies of the revolution’7 lost their lives over the following year, as the revolutionaries sought to purge themselves of those who had opposed them, or represented the ancien regime, during what would be later termed ‘the Terror’.

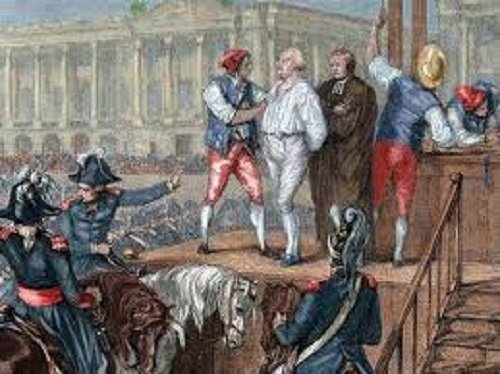

Joseph Garat (1749-1833) Proclaims the Arrest of King Louis XVI (1754-93), illustration by H. de la Charlerie,

"imagines how that moment may have appeared when the King of France was no-longer treated like the sovereign of his country"

image source

According to both Michelet, and Lamartine, “by killing the defenceless monarch, the Jacobins had awakened and unleashed tremendous sympathy that purified the monarchy in the public imagination, laying the psychological and moral groundwork for the Restoration.”8 Public sympathies had swung back from the revolution to the monarchy, slowing considerably the momentum of the changes taking place regarding the formation of a solid republican-led country. Michelet believed that executing the king was a ‘terrible miscalculation’ because ‘as a viable head of state and as a representative of monarchical ideology, the king had already ceased to exist’9 and that should have been as far as things needed to go. Lamartine felt that “the Revolution’s recourse to violence and expediency was its doom; the blood of the king cost the Jacobins the republic” and going so far as to comment that the act ‘poisoned’, for many years afterwards, the ‘idea of a republic’.10 In part, though, it made the country ‘grow up’. In the words of Habermas, the French ‘occupants of positions of authority’ broke ‘with mythological thought’ and allowed the ‘emergence of a rationalised world view’. “In short, the speeches made at the trial of Louis XVI, or rather the debate over whether he could be tried, marks the creation of a new principle of social integration, one no longer based on the myth of the divine right of the king, but on putatively universal rights of the human subject.”11 It was believed that the King had ‘two bodies’; one was the physical human body and the other was the divine body, which passed from King to King upon death, and was a direct emissary from God. Therefore the King was only answerable to God, not the people. As Saint-Just warned the Convention in 1792, “this man [the king] must reign or die. He will prove to you that all his acts were acts of state, to sustain an entrusted power; for in treating with him so, you cannot make him answer for his hidden malice; he will lose you in the vicious circle created of your own accusations.”12 Pro-royalists tried to utilise the symbolism of the king being like Christ, and that executing Louis would be directly defying the absolute authority of God, thus putting all French citizens at risk of divine retribution. Some historians went so far as to liken the sacrifice of the king for his people to that of Christ when he died so that his people could be saved.

Louis XVI Saying Farewell to his Family - by Mather Brown, cir. 1793

image source

Although the monarchy had been abolished in 1791, and a new constitution put in place, keeping the King alive, or even having him assassinated, would not have truly allowed for the discontinuation of the traditional monarchical rulership of France. In order to become an effective republic, the ‘divine right of kings’ had to come into question, and the myth expelled from the minds of the people. It certainly wasn’t a clean transition though. “So clearly did the people perceive the death of the king as an attack upon the Christian underpinnings of French society and as a sign of the destruction of their meaningfully-ordered universe that, following the decapitation of Louis XVI, many drowned themselves, cut their own throats, or went mad.”13 These acts, and those of the politically-ambitious Napoleon Bonaparte – who declared himself Emperor before eventually being exiled, forced the return of a titular King, leading only a constitutional monarchy though, with Louis XVIII later taking the throne during the Bourbon Restoration. Louis XVI was the last French king ever to be executed. An underlying problem with the decision to execute the king was that there was always some question as to the intent of his machinations surrounding the counter-revolution movement, and whether he was truly prepared to accept being a constitutional monarch. There was very little solid evidence to either prove or disprove his intentions, some of which only came to light long after Louis’s death, and was still difficult to draw definite conclusions over. Most of what was taken into consideration was circumstantial, or implied, or taken out of context, where a written phrase in a letter could be taken more than one way, or a secret meeting could be seen as sinister rather than innocent by those who were more than willing to see conspiracies going on. It certainly made having an accurate and fair trial almost impossible, and to put more pressure on the Convention there were fearful rumours being heard by the deputies while they were voting on the fate of Louis Capet, that if the death penalty was not the winning vote then the sans-culottes would ‘storm the Temple and massacre its prisoners, not to mention the Convention itself.’14 So not only did the deputies have to decide the fate of someone who had previously held office by ‘divine right’, they had the added pressure of having to consider the consequences to many other people at risk, including themselves. They also found out to their cost, after the execution of Louis, that there would be international consequences from their decision. ‘The blood of the Most Christian King offered defiance to all who questioned the French Revolution’s achievements, or its direction.’15 Political negotiations began between countries who saw themselves adversely affected by France’s decision to not only execute their king, but to bring in a republican system, and then have the temerity to start waging war against their neighbours. As these countries still operated under some form of monarchy state, they all felt that the decision of the French people to disengage from their monarchy could have adverse consequences to their own political systems. So, ‘within months of Louis XVI’s execution, most of the states of Europe were openly committed to fighting France.’16 Thus, within a year of France’s victorious international campaign, all the achievements had been reversed; although this did not stop it from later regrouping and trying again with new ambitions and other campaigns.

the execution (artist unknown)

image source

In life, Louis XVI, King of France, led a country which was crying out for change. But Louis had proved himself to be a weak leader, slow to make decisions, and often being far too cautious to take control in a way which would have proved useful to his citizens. Anger, frustration, and fear had brought on the Revolution which led to the eventual imprisonment, trial and execution of Louis Capet, citizen and alleged traitor of France. In death he became an object of pity and a symbol of sacrifice, compared in the spilling of his blood for his people, to that of Christ. To the Jacobins his death was to be a clear message to the people that the ancien regime was also dead, and that of the new utopian republic was born. They brought in a new, harsher system of justice, which saw a reign of terror for the citizens as thousands were murdered in a great purging of pro-royalists. But in doing so they did the republican system more harm than good; they had concentrated their efforts on justice with little regard to reforming a workable constitution. They’d also made instant enemies of surrounding countries, so had both internal and external struggles to deal with. The execution of Louis had not brought the instant change in fortune for France that had been touted and expected, although it did force the country to ‘grow up’, drop the mythological divine right of monarchical rulership, and force the people into taking responsibility themselves, for themselves. It was a harsh lesson, and one that did not go smoothly - many paid dearly for it with their lives – but eventually France settled down into the republican system that it had so violently desired.

French First Republic, 1792-1804 (flag)

motto: Liberté, égalité, fraternité, ou la mort!

(Liberty, equality, brotherhood, or the death!)

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

Endnotes:

1 Dunn, Susan. The Deaths of Louis XVI: Regicide and the French Political Imagination. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 15.

2 ibid., p. 16.

3 ibid., p. 19.

4 ibid., p. 21.

5 ibid. Michelet and Lamartine: Regicide, Passion, and Compassion. History and Theory. 28:3, 1989, p. 281. Retrieved 13 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505180

6 ibid. The Deaths of Louis XVI: Regicide and the French Political Imagination. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 77.

7 Reign of Terror, retrieved 25 May 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reign_of_Terror

8 Dunn, Susan. Michelet and Lamartine: Regicide, Passion, and Compassion. History and Theory. 28:3, 1989, p. 275. Retrieved 13 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505180

9 ibid., p. 279. Retrieved 13 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505180

10 ibid., p. 290. Retrieved 13 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505180

11 How, Alan R. Habermas, History and Social Evolution: Moral Learning and the Trial of Louis XVI. Sociology 35:1, p. 10, 2001. Retrieved 12 May 2010, from: http://club.fom.ru/books/how.pdf

12 ibid., p. 13, 2001. Retrieved 12 May 2010, from: <http://club.fom.ru/books/how.pdf >

13 Dunn, Susan. Camus and Louis XVI: An Elegy for the Martyred King. The French Review 62:6, 1989, p. 1034. Retrieved 16 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/394839

14 Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002, p. 196.

15 ibid., p. 196.

16 ibid., p. 202.

References:

Baecque, Antoine de. From Royal Dignity to Republican Austerity: The Ritual for the Reception of Louis XVI in the French National Assembly (1789-1792). The Journal of Modern History. 66:4, 1994, pp. 671-696. Retrieved 17 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2125154

Campbell, Peter R., Thomas E. Kaiser, Marisa Linton, eds. Conspiracy in the French Revolution. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2007.

Crook, Malcolm. Elections in the French Revolution: An apprenticeship in democracy, 1789-1799. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996.

DiPadova, Theodore A. The Girondins and the Question of Revolutionary Government. French Historical Studies. 9:3, 1976, pp. 432-450. Retrieved 19 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/286230

Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002.

Dunn, Susan. Camus and Louis XVI: An Elegy for the Martyred King. The French Review 62:6, 1989, pp. 1032-1040. Retrieved 16 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/394839

Dunn, Susan. The Deaths of Louis XVI: Regicide and the French Political Imagination. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Dunn, Susan. Michelet and Lamartine: Regicide, Passion, and Compassion. History and Theory. 28:3, 1989, pp. 275-295. Retrieved 13 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505180

Dwyer, Philip G, Peter McPhee. The French Revolution and Napoleon: a Sourcebook. Oxon: Routledge, 2002.

Freeman, Andrew, ed. The Compromising of Louis XVI: The Armoire de Fer and the French Revolution. Exeter: University of Exeter, 1989.

Goldstein, Marc Allan, ed.; trans. Social and Political Thought of the French Revolution 1788-1797: An Anthology of Original Texts. New York: Peter Laing Publishing, 1997.

How, Alan R. Habermas, History and Social Evolution: Moral Learning and the Trial of Louis XVI. Sociology 35:1, pp. 177-194, 2001. Retrieved 12 May 2010, from: http://club.fom.ru/books/how.pdf

Hunt, Lynn. The World We Have Gained: The Future of the French Revolution. The American Historical Review. 108:1, 2003, pp. 1-19. Retrieved 12 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3090696

Jones, Colin. The Longman Companion to the French Revolution. Essex: Addison Wesley Longman Ltd., 1998.

Jordan, David P. The King’s Trial: The French Revolution vs. Louis XVI. London: University of California Press, 1979.

Kennedy, Michael L. The ‘Last Stand’ of the Jacobin Clubs. French Historical Studies. 16:2, 1989, pp. 309-344. Retrieved 17 May 2010, from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/286614

Livesey, James. Making Democracy in the French Revolution. London: Harvard UP, 2001.

Price, Munro. 8Louis XVI and Gustavus III: Secret Diplomacy and Counter-Revolution, 1791-1792*. The Historical Journal. 42:2, 1999, pp. 435-466. Retrieved 14 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3020995

Reign of Terror, retrieved 25 May 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reign_of_Terror

Sydenham, Michael J. The Montagnards and Their Opponents: Some Considerations on a Recent Reassessment of the Conflicts in the French National Convention, 1792-93. The Journal of Modern History. 43:2, 1971, pp. 287-293. Retrieved 9 May 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1876547

(extra tags: #geopolis #france #culture #minnowsupport #royalty)

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

Why join discord room? Here are 10 reasons why.<

Enjoying the bump? Please consider supporting your fellow Kiwis with a delegation. How? Read here.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

Congratulations @ravenruis! You have completed the following achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Keep on writing and stay curious!

Interesting essay. I think the view of the execution is greatly effected by the years and years of revolution that followed. Had the first republic stood the test of time, the execution of Louis XVI would have been viewed very differently by history. Nice essay @ravenruis

@ravenruis Thank you for not using bidbots on this post and also using the #nobidbot tag!