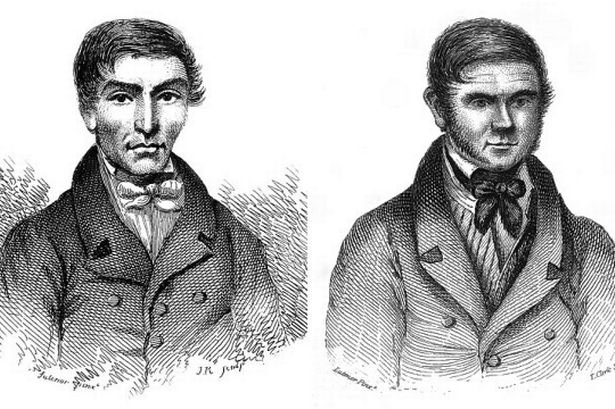

Burke & Hare, The Body Snatchers.

In Regency Edinburgh, Burke and Hare took the crime of body-snatching to its ultimate extreme — and in doing so, guaranteed their lasting infamy.

Body snatchers, also known as resurrectionists, were seedy individuals who looked to supply the growing demand for cadavers by digging up the deceased to sell on to eager medical students for study. Burke and Hare, instead of exhuming corpses, chose to murder their victims to make money

Both men came from humble origins. Burke was an Ulsterman, the son of a labourer, born in 1792 in Urney, County Tyrone. He struggled to make a living — working at various times as a servant, baker, weaver and cobbler — and maintain his family. Eventually, after a spell in the Donegal Militia, he left them behind and, around 1818, moved to Scotland, where he promised to send money home and lift them out of poverty.

Instead, he found both a mistress, Helen McDougal, and a job as a navvy on the Union Canal, and soon forgot about his Irish wife and children. He also met another Irish navvy — Armagh-native William Hare, a former farm labourer and servant who was known for his incredibly bad temper. Hare and his wife, Margaret, ran a boarding house in Edinburgh — and Burke and McDougal needed cheap accommodation. The two couples were soon living together with the men becoming close friends both at work and home.

Burke and McDougal were not the only ones paying for lodging with the Hares. Another was Donald Bark, a former soldier, who died of natural causes one night in December 1827, having failed to pay his rent. Hare now needed money and to get rid of this unwanted, unclaimed body. He had heard that the medical doctors and students in Edinburgh always needed bodies to dissect, and an idea soon formed. He and Burke took Bark’s body in a sack to anatomist Dr Robert Knox on Surgeon’s Square, where one of his assistants eagerly paid £7 10s for the corpse. The two men split the money, Hare taking £4 5s and Hare a pound less. This was a lucrative business, for Bark had only owed £4 in rent. But how could they make a regular living out of selling dead bodies?

The answer was soon presented to them. Abigail Simpson was a poor woman from a village just outside Edinburgh. She had come into the city one day in December to get her weekly pension of 1s 6d. She had duly spent part of it on drink and had the misfortune to bump into Hare while clearly drunk. She was also old, weak and lonely, and welcomed the chance to start a conversation with the amenable Hare.

He persuaded her to come to his house to have a dram of whisky, which turned into several. Abigail began crooning old songs and became so drunk that she was invited to stay for the night. The following morning, ill and vomiting from the drink, Burke and Hare decided to take action. Burke lay on the woman’s body to stop her moving while Hare put his hands over her nose and mouth, soon stifling her. Her body was stripped, placed in a box and duly sold to Dr Knox.

Burke and Hare had now moved from selling bodies to killing them first. They were full-blown murderers and had the taste for it. Another unfortunate tenant, an old man known to posterity as Joseph, had become ill, although inconveniently for the Irishmen, he lingered on. They therefore helped him on his way, smothering him with a pillow — their favoured method of killing as it left few violent marks for anatomists to spot and they would be more likely to believe that their medical subjects had died a natural death.

A further body — this one of a 40-year- old Cheshire man, a match-seller who had been lodging at Hare’s house when Abigail Simpson was killed, but had been prostrate with severe jaundice — was soon after sold to Dr Knox for £10. There is some doubt over the order in which these unfortunate people were killed; much of what we know is taken from Burke’s own confession, but his confusion over dates suggest that there were so many victims in the end that he couldn’t remember exactly who had been killed and when.

The bodies started to pile up. They included a woman named Mary Paterson, who was persuaded to drink heavily until she lost consciousness and whose body was presented to Dr Knox so quickly that he began to harbour doubts about how Burke and Hare were obtaining these corpses, although he still paid them. In fact, Mary was especially lucrative for them — it was said that her long hair was cut off to sell on to a hairdresser, for use on his unwitting customers.

Burke stated that Mary’s body had been bought from her friends; one of Knox’s assistants responded that it was “rather a new thing for me to hear of the relatives selling the bodies of their friends.” Burke told him that if he didn’t stop ‘catechising’ him, he would stop bringing bodies. But, of course, he continued.

“Burke and Hare decided to take action”

Another victim was Mrs Ostler, a blonde, short woman about 40 years old, who worked as a washerwoman. She was visiting the house of Burke’s cousin, John Broggan, where the three men got her blind drunk. John’s wife went out to buy

a tea chest — and Mrs Ostler next left the house in that tea chest, as the pair carried it to Surgeon’s Square and returned with cash.

The pair would commonly call into Dr Knox’s rooms in the late afternoon or evening, telling one of his assistants that they “had a subject for the doctor.” Around 90 minutes later, Dr Knox would tell one assistant, Mr Paterson, to be “in the way with the keys, as it would not do to keep the parties waiting.”

Burke and Hare’s victims were commonly poor men and women, those who might not be missed by family and friends, and those who would welcome the chance to drink with the two men and their partners in the house in Tanner’s Close.

However, they got complacent, and it was with their last male ‘subject’ that Burke and Hare made a fatal mistake. They picked someone they thought would not be missed — a local homeless man, both physically and mentally disabled. But unfortunately for them, the man’s disabilities and unfortunate status that led to him begging and performing in the streets for money also meant that he was well known to Edinburgh’s natives.

James Wilson was just 18 years old and known to locals as ‘Daft Jamie’. Burke and Hare underestimated how much his absence would be noticed and just how strong the young man was. Their usual method was to get their subjects drunk before smothering them but Daft Jamie didn’t want to drink much. Then, when the two men tried to kill him, he struggled valiantly for his life, causing them more effort than usual to subdue him.

But subdue him they did, and duly brought his corpse to Dr Knox’s team in a large chest, being paid their usual fee. However, when the body was re-examined the next morning by Knox’s assistants, one commented, “That looks very like Daft Jamie!” The others present all agreed, and then wondered how the body had been obtained — had Jamie’s friends sold his body onto Burke and Hare?

Soon, however, a report that Jamie had gone missing reached Surgeon’s Square. The dissection of the body went ahead as planned, but questions were being raised about how a young and physically healthy man had suddenly died and been brought along to be cut up by two men who were not previously known to him.

The first body to have been sold to the anatomists by Burke and Hare had been one of Hare’s tenants. At the end, it was two more of his tenants who put an end to the men’s grim career. They had been smothering their 16th and final victim, Margaret Docherty (also known as Mary Mitchell and Margery Campbell), in their house, but despite being a middle-aged woman, she put up such a struggle against the two strong men that the noise was heard by tenants James and Ann Grey.

Ann, in fact, claimed she had heard a woman’s voice shouting “Murder!” but because she was used to the lack of peace at Hare’s house, she and her husband had simply gone elsewhere for the night for a bit of quiet sleep, rather than enquire as to what was going on.

When they returned the next morning, they noted that Mrs Hare was behaving oddly, telling them not to go near the bed in one of the rooms. When she went out, the intrigued Mr and Mrs Grey went to have a look and when they found Docherty’s body, they immediately ran to the police. In the meantime, the corpse was quickly removed and it was later found by police in Dr Knox’s dissection room. Bizarrely, Knox was never called to give evidence at the pair’s trial and he escaped prosecution altogether. There was little direct evidence to tie him to the murders, although many wondered how such a prominent medical expert did not suspect where this seemingly endless supply of fresh corpses came from.

The population of Edinburgh was outraged by this miscarriage of justice and an angry mob attacked his house and burned effigies of Knox in the streets. Although he never faced criminal charges, he was slowly forced out of the Scottish academic scene and eventually moved to London, his reputation in tatters. Despite Hare’s clear involvement in the murders, he too never faced justice. Instead, he was allowed to turn king’s evidence, making clear Burke’s role in the crimes. His wife, in turn, was judged to have known about the murders, and to have been involved, but to have acted under duress because of her husband’s temper. Burke was made the sole scapegoat for his and Hare’s many offences, and at of. They said for his face “has an agreeable, often a pleasant expression” at odds with his reputation. Regardless of this, though, he was sent to the gallows on 28 January 1829 and his lifeless remains sent to Edinburgh University. Tickets were sold for his dissection, making it a rather gory form of theatre for the city’s population.

Burke was dead and Hare as good as dead, as he had to hide out of sight of those who hated him, yet they both lived on — and still do — in the public’s imagination. Those attending trials would cry out, “Burke him! Hare him!” in regard to the accused. Other body snatchers, including John Bishop, who claimed to have obtained and sold between 500 and 1,000 bodies over a 12-year ‘career’ ending in 1831, became known as ‘the London Burkers’.

Those who, as children, had lived through the ghoulish events, as old people recited to their grandchildren the rhyme they had used when they played: “Up the close and down the stair, in the house with Burke and Hare. Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief, Knox the man who buys the beef.”

Today, the death mask of William Burke is on display in Edinburgh at the William Burke Museum, together with a book said to have been made from skin taken from his dead body after he was hanged. It seems rather appropriate an end for one of the men who made a living from other people’s bodies.

“However, they got complacent, and it was with their last male ‘subject’ that Burke and Hare made a fatal mistake”