Prehistory of God Indra: From the Farmers of Oxus Civilization to the Rigvedic Tribes

Indra, that über-masculine Hindu god of war, was first revered by goddess-worshipping farmers.

Introduction

In Hindu mythology, most gods and goddesses have incredibly baroque backstories, countless honorable titles, and highly detailed domains of power. Scholars and mystics alike spend lifetimes (honorably) learning the ins and outs of these particulars. Yet centuries before Hinduism consolidated into the complex world religion we know today (between 500 BCE and 500 CE [1]), many of its gods and goddesses existed in much more rustic and provincial forms: they were once simpler in the scope of their concerns (and in their powers) than they became as society increased in complexity.

This post briefly follows one of these god-ancestors, showcasing a few interesting influences upon God Indra's metamorphosis into His modern character. Here, we see a portrait of Indra in His earliest known forms: in the Eurasian steppes, among both nomadic warrior-pastoralists, and among goddess-worshipping farmers -- well before he transformed into the mustachioed, elephant riding, galavanting trickster of medieval and modern Hindu mythology (see 2).

The (Almost) Prehistoric Origins of God Indra

All information presented below is summarized from Anthony (2007 [3]) unless otherwise noted.

The earliest written record of His name, Indara, appears in the Mittani culture of Northern Syria (1500-1350 BCE). These people spoke Hurrian languages, yet the name Indara is not Hurrian: it is Old Indic, belonging to the languages of those who composed the Rig Veda (Sanskrit is one dialect of Old Indic).

The Mittani upper-classes used lots of Old Indic terms: royal and military titles; military tactics and ritual practices, as well as all things equestrian and chariot-related were Old Indic in name, if you asked the Mittani. Why were they using terms from this other language?

Answer: The Mittani were invaded by Old Indic speaking warriors who loved horses and chariots; elaborate rituals, and battling for the spoils of war. These guys took over the aristocracy, the religious elite, and the military of the Mittani. While the commoners continued to speak Hurrian languages, the elite spoke Old Indic. When the Hurrian languages eventually retook the Mittani court, many Old Indic words stuck around.

As will be seen, invaders from the steppe swooping-in on chariots and colonizing/integrating-with preexisting cultures has always been the central propeller of Indra's prominence within the world of man.

Who were the invaders? (Indra before the Mittani)

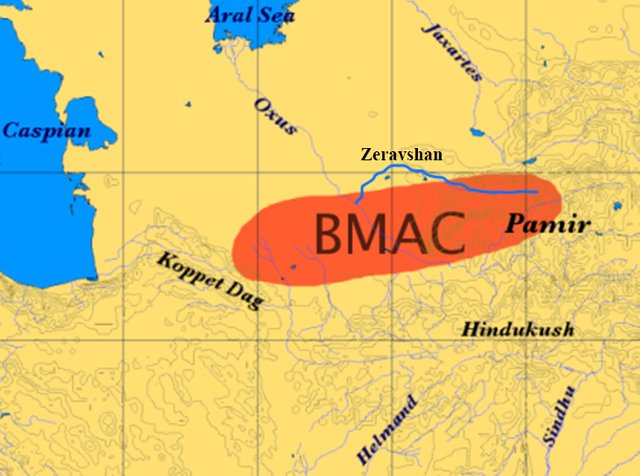

The Old Indic speaking conquerers of Mittani emerged from a culture of nomads that began around 1800 BCE, when an older group of nomads from high in the central asian steppe began moving in and making contact (probably both violent and pragmatic) with farming societies, in portions of what are today called Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan (pre-invasion culture of this time and place is often referred to as the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), or Oxus culture, as it is here. This contact zone was largely along/near the Zeravshan river (see image below).

Through centuries of invasion and cohabitation, the pastoral life-way overtook the agricultural one in the Oxus cultures, with the stone-walled cities of the farmers being completely abandoned by around 1600 BCE. Soon after, clay statues of horseback riders begin appearing in the region (1700 BCE), and the culture of goddess-worshipping farmers was replaced by that of the patriarchal nomadic invaders. In short, life in the region shifted from sedentary farming to nomadic pastoralism.

Yet the beliefs and practices of the dying Oxus culture did, also, undoubtedly assimilate into those of the Eurasian pastoralists: God Indra might have existed in some form or another among the original invaders, but it was not until their incursion into the Oxus region that the Indra we know today, the God of war and victory; the lover of soma (a strong, stimulating drink) emerged.

It seems that, ironically, Indra was a God of the invaded and decimated Oxus culture: both the name of Indra and the word soma are derived from the language of the Oxus people. Indeed, Indo-Iranian traditions of both past and present have their own god of victory and war, Verethraghna, who seems to have provided the basic template for Indra. A cognate of Verethraghna literally means "smiter of resistance".

The next expansion: God Indra and the Rig Veda

Indra became the most important deity of this syncretic culture; centrally related to victory in battle and the ritual consumption of Soma. By 1500 BCE, these warlike people, who had been ruminating on Indra's glorious reputation for centuries, began to expand again, brining Indra along: they went west into Syria (as discussed above), taking the spoils of war and leaving their vocabulary, along with other aspects of their culture.

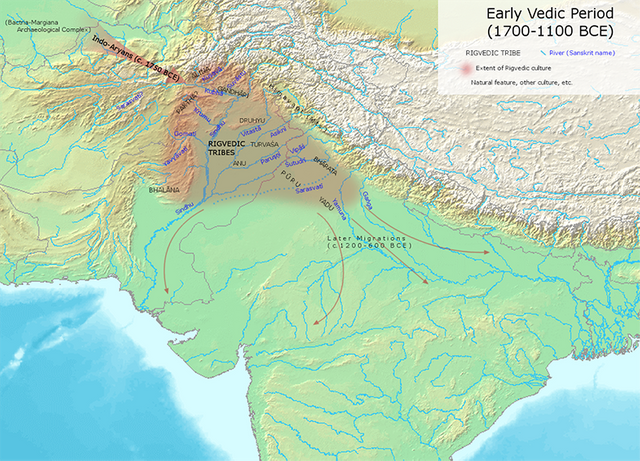

Simultaneously, they went east toward the Punjab. This group of invaders swooped into what is today northern India (see below), colonizing and integrating; killing and intermarrying, teaching and learning. These syncretic peoples eventually emerged into what archaeologists and historians call today the Rigvedic tribes.

What came afterward, between 1500 and 1300 BCE was the Rig Veda: the canonization of myths, rituals, and beliefs of the invading nomads mixed (to some extent) with stories and beliefs of the indigenous people in the region.

The Rig Veda is a -- if not the -- central root of medieval and modern Hinduism, and verses from this text are used in Hindu rites of passage to this day (see the image below from a Hindu wedding ceremony fire).

Numbering 250, hymns in reverence of Indra comprise nearly 1/4th of the entire Rig Veda. They detail His adventures, His virtues, His love of Soma, and His deeds in service to humanity. They are a definitive testament to what a big deal Indra was to the writers of the Rig Veda. Thanks to the efforts of historical linguists and archaeologists, we now know they did not appear from nothingness, but rather emerged from a rich history of inter-cultural interactions (much of it stained in blood, obviously).

An invitation to analysis

Indra, the God of victory and war, along with His beloved Soma are sexy topics indeed, and they are epic in their scope, age, and interpretability.

Yet, don't let's forget that this rugged, nomadic pastoralist deity (in all his male power-tripping) emerged not from the patriarchal steppe warriors but from more benign, more goddess-focused farmers.

As with most of my posts, I'd like nothing more than to have the conclusion written in the comments by my fellow Steemians.

If you do comment, please do remember that blog posts have to be kept short, so an infinity of information is necessarily omitted here.

All images used here were listed as public domain

References

1. Hinduism in the World. (2017). Retrieved August 09, 2016, from http://pluralism.org/timeline/hinduism-in-the-world/

2. Perry, E. D. (1885). Indra in the Rig-veda. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 11, 117-208.

3. Anthony, D. W. (2010). The horse, the wheel, and language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton University Press.

Fascinating thank you. Will you be do a series on the origins of each (I dont know how many there are) Gods of the Hindu pantheon?

Thats a good idea. I'd like to do that. Time is the only constraint for me, I guess, although if I got really deep into that project I might start believing I can just finish the task after I reincarnate.

@titanius followed!

Thanks. This is interesting, but perhaps incomplete.

I'd speculate that the location that you mention the PIE migrants encounter Soma as BMAC is incorrect. Soma has since been identified as the species Ephedra pachyclada that yields the stimulant Ephedrine. This particular species is geographically bound to the hills of Afghanistan. The identification was based not just on morphology, but also from the Parsis of Bombay, who had been continuously using Soma in their rituals, bringing it in the dried form from Afghanistan.

However, it is probably true to say that the migrating PIE pastoralists did borrow much from the BMAC, including linguistic innovations as well as mythological characters (for instance, Indra and Vishnu)