A dangerous parasitic illness spread by bugs that bite people's faces at night is spreading in the US, doctors warn

The name "kissing bug" doesn't quite communicate the danger of the infection that insects with that moniker can spread.

These bloodsucking bugs, called triatomine bugs, spread a parasitic illness called Chagas disease. Left untreated, Chagas causes serious cardiac or intestinal complications in about 30% of patients, according to the CDC. These complications can lead to heart failure and sudden death.

Because many people don't show signs of infection, medical researchers have described Chagas as a "silent killer."

Chagas has typically been found in Central and South America, but the disease is becoming more common in the US, Canada, Europe, Australia, and Japan, according to a recent statement from American Heart Association (AHA) and the Inter-American Society of Cardiology. The groups warn that doctors outside Latin America must become more aware of the disease so they can recognize, treat, and control it.

The AHA estimates that there are approximately 300,000 people infected with Chagas in the US right now, and approximately 6 million infected people around the world.

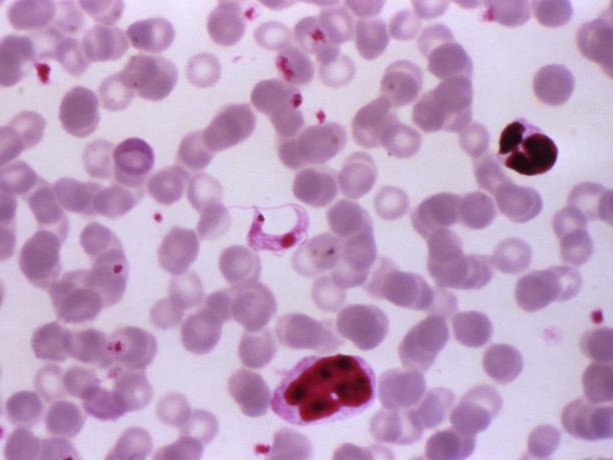

Under a magnification of 1000X, a micrograph reveals Trypanosoma cruzi parasites in a blood smear. This parasite, T. cruzi, is the causative agent for Chagas disease.

How Chagas infections happen

Chagas infections occur in a disturbing fashion.

During the night, certain species of triatomine bugs crawl onto people, dogs, or other mammals to feed. They often bite on the face, especially near the eyes or mouth - hence the "kissing bugs" name.

Out of more than 100 species of triatomine bugs, about 12 are considered important transmitters of Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasite that causes Chagas.

When these bugs eat, they typically defecate, leaving feces that may contain the parasite. If these feces get rubbed into the bite wound or into mucous membranes in the eye or mouth, people can get infected.

Most people don't show signs of infection, though some people develop swollen eyelids if that's where the infection first occurs. During the early phase of infection, some people experience fairly common symptoms of sickness like fever, fatigue, body aches, headaches, or a rash, according to Texas A&M's Chagas research team.

In some cases, people may experience diarrhea or vomiting, and a small percentage of young children can experience swelling in the heart or brain that can lead to death.

Doctors can diagnose the condition with blood tests and treat it with antiparasitic medications. But if patients aren't treated, they can develop the chronic form of the illness, and about 30% of those develop an enlarged heart. That can lead to further complications, including stroke, irregular heart rate, or heart failure.

A growing threat

In the US, there are at least 11 species of triatomine bugs, some of which transmit Chagas. In the US, the infection is most common in Southern states, including Texas, Florida, and California.

As Chagas disease has spread and infected people have migrated to different parts of the world, other forms of transmission have become more common. Chagas can also be passed through blood transfusions, organ donation, and from pregnant women to their children.

"Transmission through these routes is a global problem and can occur wherever infected individuals reside," the authors of the recent warning wrote.

This isn't the first time in recent years that doctors have sounded the alarm about Chagas. Epidemiologist Melissa Nolan Garcia of Baylor University made a similar statement after presenting research on Chagas rates in Texas at a meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2014.

"We were astonished to not only find such a high rate of individuals testing positive for Chagas in their blood, but also high rates of heart disease that appear to be Chagas-related," Garcia said.

The illness has continued to spread since then, without sufficient awareness, according to the new statement.

Chagas has long been considered a neglected parasitic infection. Local transmission has largely been stopped in some places where the disease used to spread, like Chile, but further spread and blood supply contamination are making the disease a broader concern. It's an infection that we need far better information on, according to the statement.

The new statement also says that estimates of infected populations need to be improved, as do diagnostic and treatment options. Particularly urgent are new, less toxic drugs that are more effective and can be taken during pregnancy, unlike current options.

If these issues aren't addressed soon, the number of cases - and severe heart problems related to those cases - could continue to climb.