Tea and History of Tea Culture

Tea is an aromatic beverage commonly prepared by pouring hot or boiling water over cured leaves of the Camellia sinensis, an evergreen shrub native to Asia. After water, it is the most widely consumed drink in the world. There are many different types of tea; some teas, like Darjeeling and Chinese greens, have a cooling, slightly bitter, and astringent flavour, while others have vastly different profiles that include sweet, nutty, floral or grassy notes.

Tea originated in Southwest China, where it was used as a medicinal drink. It was popularized as a recreational drink during the Chinese Tang dynasty, and tea drinking spread to other East Asian countries. Portuguese priests and merchants introduced it to Europe during the 16th century. During the 17th century, drinking tea became fashionable among Britons, who started large-scale production and commercialization of the plant in India to bypass the Chinese monopoly.

The term herbal tea usually refers to infusions of fruit or herbs made without the tea plant, such as steeps of rosehip, chamomile, or rooibos. These are sometimes called tisanes or herbal infusions to prevent confusion with tea made from the tea plant.

The history of tea is long and complex, spreading across multiple cultures over the span of thousands of years. Tea likely originated in southwest China during the Shang dynasty as a medicinal drink. An early credible record of tea drinking dates to the 3rd century AD, in a medical text written by Hua Tuo. Tea was first introduced to Portuguese priests and merchants in China during the 16th century. Drinking tea became popular in Britain during the 17th century. The British introduced tea production, as well as tea consumption, to India, in order to compete with the China monopoly on tea.

A tea plantation in Ciwidey, Bandung in Indonesia

Processing and classification

Tea is generally divided into categories based on how it is processed.[80] At least six different types are produced:

White: wilted and unoxidized;

Yellow: unwilted and unoxidized but allowed to yellow;

Green: unwilted and unoxidized;

Oolong: wilted, bruised, and partially oxidized;

Black: wilted, sometimes crushed, and fully oxidized; called (called 紅茶 [hóngchá], "red tea" in Chinese tea culture);

Post-fermented: green tea that has been allowed to ferment/compost (called 黑茶 [hēichá] "black tea" in Chinese tea culture).

The most common are white, green, oolong, and black.

After picking, the leaves of C. sinensis soon begin to wilt and oxidize unless immediately dried. An enzymatic oxidation process triggered by the plant's intracellular enzymes causes the leaves to turn progressively darker as their chlorophyll breaks down and tannins are released. This darkening is stopped at a predetermined stage by heating, which deactivates the enzymes responsible. In the production of black teas, halting by heating is carried out simultaneously with drying. Without careful moisture and temperature control during manufacture and packaging, growth of undesired molds and bacteria may make tea unfit for consumption.

Although single-estate teas are available, almost all tea in bags and most loose tea sold in the West is blended. Such teas may combine others from the same cultivation area or several different ones. The aim is to obtain consistency, better taste, higher price, or some combination of the three.

Tea easily retains odors, which can cause problems in processing, transportation, and storage. This same sensitivity also allows for special processing (such as tea infused with smoke during drying) and a wide range of scented and flavoured variants, such as bergamot (found in Earl Grey), vanilla, and spearmint.

Additions

Tea is often consumed with additions to the basic tea leaf and water. These can be grouped into flavourings added to the tea in processing before sale and those added during preparation or drinking. The former are often floral, herbal or spice flavourings and the latter include milk, sugar, lemon, among other things.

Milk

Black tea is often taken with milk

The addition of milk to tea in Europe was first mentioned in 1680 by the epistolist Madame de Sévigné. Many teas are traditionally drunk with milk in cultures where dairy products are consumed. These include Indian masala chai and British tea blends. These teas tend to be very hearty varieties of black tea which can be tasted through the milk, such as Assams, or the East Friesian blend. Milk is thought to neutralise remaining tannins and reduce acidity. The Han Chinese do not usually drink milk with tea but the Manchus do, and the elite of the Qing Dynasty of the Chinese Empire continued to do so. Hong Kong-style milk tea is based on British colonial habits. Tibetans and other Himalayan peoples traditionally drink tea with milk or yak butter and salt. In Eastern European countries (Russia, Poland and Hungary) and in Italy, tea is commonly served with lemon juice. In Poland, tea with milk is called a bawarka ("Bavarian style"), and is often drunk by pregnant and nursing women. In Australia, tea with milk is white tea.

The order of steps in preparing a cup of tea is a much-debated topic, and can vary widely between cultures or even individuals. Some say it is preferable to add the milk before the tea, as the high temperature of freshly brewed tea can denature the proteins found in fresh milk, similar to the change in taste of UHT milk, resulting in an inferior-tasting beverage. Others insist it is better to add the milk after brewing the tea, as black tea is often brewed as close to boiling as possible. The addition of milk chills the beverage during the crucial brewing phase, if brewing in a cup rather than using a pot, meaning the delicate flavour of a good tea cannot be fully appreciated. By adding the milk afterwards, it is easier to dissolve sugar in the tea and also to ensure the desired amount of milk is added, as the colour of the tea can be observed.[citation needed] Historically, the order of steps was taken as an indication of class: only those wealthy enough to afford good-quality porcelain would be confident of its being able to cope with being exposed to boiling water unadulterated with milk. Higher temperature difference means faster heat transfer so the earlier you add milk the slower the drink cools. A 2007 study published in the European Heart Journal found certain beneficial effects of tea may be lost through the addition of milk

Others

Many flavourings are added to varieties of tea during processing. Among the best known are Chinese jasmine tea, with jasmine oil or flowers, the spices in Indian masala chai, and Earl Grey tea, which contains oil of bergamot. A great range of modern flavours have been added to these traditional ones. In eastern India, people also drink lemon tea or lemon masala tea. Lemon tea simply contains hot tea with lemon juice and sugar. Masala lemon tea contains hot tea with roasted cumin seed powder, lemon juice, black salt and sugar, which gives it a tangy, spicy taste. Adding a piece of ginger when brewing tea is a popular habit of Sri Lankans, who also use other types of spices such as cinnamon to sweeten the aroma.

Different type of Tea

*Black tea

*Green tea

*Flowering tea

*Oolong tea

*Premium or delicate tea

*Pu-erh tea

*Cold brew and sun tea

To preserve the pretannin tea without requiring it all to be poured into cups, a second teapot may be used. The steeping pot is best unglazed earthenware; Yixing pots are the best known of these, famed for the high-quality clay from which they are made. The serving pot is generally porcelain, which retains the heat better. Larger teapots are a post-19th century invention, as tea before this time was very rare and very expensive. Experienced tea-drinkers often insist the tea should not be stirred around while it is steeping (sometimes called winding or mashing in the UK). This, they say, will do little to strengthen the tea, but is likely to bring the tannins out in the same way that brewing too long will do. For the same reason, one should not squeeze the last drops out of a teabag; if stronger tea is desired, more tea leaves should be used.

Tea is the most popular manufactured drink consumed in the world, equaling all others – including coffee, chocolate, soft drinks, and alcohol – combined. Most tea consumed outside East Asia is produced on large plantations in the hilly regions of India and Sri Lanka, and is destined to be sold to large businesses. Opposite this large-scale industrial production are many small "gardens," sometimes minuscule plantations, that produce highly sought-after teas prized by gourmets. These teas are both rare and expensive, and can be compared to some of the most expensive wines in this respect.

India is the world's largest tea-drinking nation, although the per capita consumption of tea remains a modest 750 grams per person every year. Turkey, with 2.5 kg of tea consumed per person per year, is the world's greatest per capita consumer.

In 2003, world tea production was 3.21 million tonnes annually.[101] In 2010, world tea production reached over 4.52 million tonnes after having increased by 5.7% between 2009 and 2010.[102] Production rose by 3.1% between 2010. In 2013, world tea production reached over 5.34 million tonnes after having increased by 6.17% between 2012 and 2013. The largest producers of tea are the People's Republic of China, India, Kenya and Sri Lanka.

Packaging

- Tea bags

- Loose tea

- Compressed tea

- Instant tea

- Bottled and canned tea

Storage

Storage conditions and type determine the shelf life of tea. Black tea's is greater than green's. Some, such as flower teas, may last only a month or so. Others, such as pu-erh, improve with age.

To remain fresh and prevent mold, tea needs to be stored away from heat, light, air, and moisture. Tea must be kept at room temperature in an air-tight container. Black tea in a bag within a sealed opaque canister may keep for two years. Green tea deteriorates more rapidly, usually in less than a year. Tightly rolled gunpowder tea leaves keep longer than the more open-leafed Chun Mee tea.

Storage life for all teas can be extended by using desiccant or oxygen-absorbing packets, vacuum sealing, or refrigeration in air-tight containers (except green tea, where discrete use of refrigeration or freezing is recommended and temperature variation kept to a minimum).

Geographic origins

"Camellia sinensis originated in southeast Asia, specifically around the intersection of latitude 29°N and longitude 98°E, the point of confluence of the lands of northeast India, north Burma, southwest China and Tibet. The plant was introduced to more than 52 countries, from this ‘centre of origin’."

Brick tea

On morphological differences between the Assamese and Chinese varieties, botanists have long asserted a dual botanical origin for tea; however, statistical cluster analysis, the same chromosome number (2n=30), easy hybridization, and various types of intermediate hybrids and spontaneous polyploids all appear to demonstrate a single place of origin for Camellia sinensis — the area including the northern part of Burma, and Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China.

Yunnan Province has also been identified as "the birthplace of tea…the first area where humans figured out that eating tea leaves or brewing a cup could be pleasant." Fengqing County in the Lincang City Prefecture of Yunnan Province in China is said to be home to the world's oldest cultivated tea tree, some 3,200 years old.

According to The Story of Tea, tea drinking likely began in Yunnan province during the Shang Dynasty (1500 BC–1046 BC), as a medicinal drink. From there, the drink spread to Sichuan, and it is believed that there "for the first time, people began to boil tea leaves for consumption into a concentrated liquid without the addition of other leaves or herbs, thereby using tea as a bitter yet stimulating drink, rather than as a medicinal concoction."

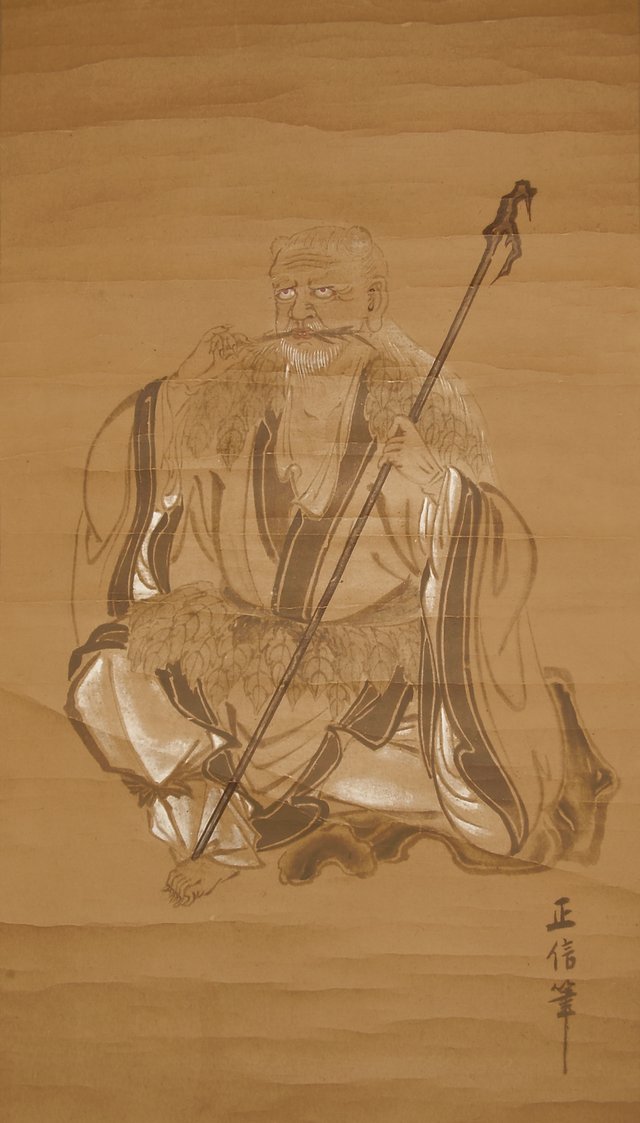

Origin myths

In one popular Chinese legend, Shennong, the legendary Emperor of China and inventor of agriculture and Chinese medicine was drinking a bowl of just boiled water due to a decree that his subjects must boil water before drinking it some time around 2737 BC when a few leaves were blown from a nearby tree into his water, changing the color. The emperor took a sip of the brew and was pleasantly surprised by its flavor and restorative properties. A variant of the legend tells that the emperor tested the medical properties of various herbs on himself, some of them poisonous, and found tea to work as an antidote. Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu's famous early work on the subject, The Classic of Tea. A similar Chinese legend goes that the god of agriculture would chew the leaves, stems, and roots of various plants to discover medicinal herbs. If he consumed a poisonous plant, he would chew tea leaves to counteract the poison.

Japanese painting depicting Shennong

A rather gruesome legend dates back to the Tang Dynasty. In the legend, Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan Buddhism, accidentally fell asleep after meditating in front of a wall for nine years. He woke up in such disgust at his weakness that he cut off his own eyelids. They fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes. Sometimes, another version of the story is told with Gautama Buddha in place of Bodhidharma.

Scholars however believe that tea drinking likely originated in the southwest of China, and that the Chinese words for tea themselves may have been originally derived from the Austro-Asiatic languages of the people who originally inhabited that area.

Whether or not these legends have any basis in fact, tea has played a significant role in Asian culture for centuries as a staple beverage, a curative, and a status symbol. It is not surprising, therefore, that theories of its origin are often religious or royal in nature.

Global expansion

A conical urn-shaped silver-plated samovar used for boiling water for tea in Russia and some Middle eastern countries

The earliest record of tea in a more occidental writing is said to be found in the statement of an Arabian traveler, that after the year 879 the main sources of revenue in Canton were the duties on salt and tea. Marco Polo records the deposition of a Chinese minister of finance in 1285 for his arbitrary augmentation of the tea taxes. The travelers Giovanni Batista Ramusio (1559), L. Almeida (1576), Maffei (1588), and Teixeira (1610) also mentioned tea. In 1557, Portugal established a trading port in Macau and word of the Chinese drink "chá" spread quickly, but there is no mention of them bringing any samples home. In the early 17th century, a ship of the Dutch East India Company brought the first green tea leaves to Amsterdam from China. Tea was known in France by 1636. It enjoyed a brief period of popularity in Paris around 1648. The history of tea in Russia can also be traced back to the seventeenth century. Tea was first offered by China as a gift to Czar Michael I in 1618. The Russian ambassador tried the drink; he did not care for it and rejected the offer, delaying tea's Russian introduction by fifty years. In 1689, tea was regularly imported from China to Russia via a caravan of hundreds of camels traveling the year-long journey, making it a precious commodity at the time. Tea was appearing in German apothecaries by 1657 but never gained much esteem except in coastal areas such as Ostfriesland. Tea first appeared publicly in England during the 1650s, where it was introduced through coffeehouses. From there it was introduced to British colonies in America and elsewhere.

China : History of tea in China

The Chinese have consumed tea for thousands of years. The earliest physical evidence known to date, found in 2016, comes from the mausoleum of Emperor Jing of Han in Xi'an, indicating that tea was drunk by Han Dynasty emperors as early as the 2nd century BC. The samples were identified as tea from the genus Camellia particularly via mass spectrometry. and written records suggest that it may have been drunk earlier. People of the Han Dynasty used tea as medicine (though the first use of tea as a stimulant is unknown). China is considered to have the earliest records of tea consumption, with possible records dating back to the 10th century BC. Note however that the current word for tea in Chinese only came into use in the 8th century AD, there are therefore uncertainties as to whether the older words used are the same as tea. The word tu 荼 appears in Shijing and other ancient texts to signify a kind of "bitter vegetable" (苦菜), and it is possible that it referred to a number of different plants, such as sowthistle, chicory, or smartweed, including tea. In the Chronicles of Huayang, it was recorded that the Ba people in Sichuan presented tu to the Zhou king. The state of Ba and its neighbour Shu were later conquered by the Qin, and according to the 17th century scholar Gu Yanwu who wrote in Ri Zhi Lu (日知錄): "It was after the Qin had taken Shu that they learned how to drink tea."

The first known reference to boiling tea came from the Han dynasty work "The Contract for a Youth" written by Wang Bao where, among the tasks listed to be undertaken by the youth, "he shall boil tea and fill the utensils" and "he shall buy tea at Wuyang". The first record of cultivation of tea also dated it to this period (Ganlu era of Emperor Xuan of Han) when tea was cultivated on Meng Mountain (蒙山) near Chengdu. From the Tang to the Qing dynasties, the first 360 leaves of tea grown here were picked each spring and presented to the emperor. Even today its green and yellow teas, such as the Mengding Ganlu tea, are still sought after. An unknown Chinese inventor was also the first person to invent a tea shredder. An early credible record of tea drinking dates to 220 AD, in a medical text Shi Lun (食论) by Hua Tuo, who stated, "to drink bitter t'u constantly makes one think better." Another possible early reference to tea is found in a letter written by the Qin Dynasty general Liu Kun. However, before the mid-8th century Tang dynasty, tea-drinking was primarily a southern Chinese practice. It became widely popular during the Tang Dynasty, when it was spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

Laozi, the classical Chinese philosopher, was said to describe tea as "the froth of the liquid jade" and named it an indispensable ingredient to the elixir of life. Legend has it that master Lao was saddened by society's moral decay and, sensing that the end of the dynasty was near, he journeyed westward to the unsettled territories, never to be seen again. While passing along the nation's border, he encountered and was offered tea by a customs inspector named Yin Hsi. Yin Hsi encouraged him to compile his teachings into a single book so that future generations might benefit from his wisdom. This then became known as the Dao De Jing, a collection of Laozi's sayings.

During the Sui Dynasty (589–618 AD) tea was introduced to Japan by Buddhist monks.

The Tang Dynasty writer Lu Yu's (simplified Chinese: 陆羽; traditional Chinese: 陸羽; pinyin: lùyǔ) Cha Jing (The Classic of Tea) (simplified Chinese: 茶经; traditional Chinese: 茶經; pinyin: chá jīng) is an early work on the subject. (See also Tea Classics) According to Cha Jing tea drinking was widespread. The book describes how tea plants were grown, the leaves processed, and tea prepared as a beverage. It also describes how tea was evaluated. The book also discusses where the best tea leaves were produced. Teas produced in this period were mainly tea bricks which were often used as currency, especially further from the center of the empire where coins lost their value. In this period, tea leaves were steamed, then pounded and shaped into cake or brick forms.

A Ming Dynasty painting by artist Wen Zhengming illustrating scholars greeting in a tea ceremony

During the Song Dynasty (960–1279), production and preparation of all tea changed. The tea of Song included many loose-leaf styles (to preserve the delicate character favored by court society), and it is the origin of today's loose teas and the practice of brewed tea. A new powdered form of tea also emerged. Steaming tea leaves was the primary process used for centuries in the preparation of tea. After the transition from compressed tea to the powdered form, the production of tea for trade and distribution changed once again.

The Chinese learned to process tea in a different way in the mid-13th century. Tea leaves were roasted and then crumbled rather than steamed. By the Yuan and Ming dynasties, unfermented tea leaves were first pan-fried, then rolled and dried. This stops the oxidation process which turns the leaves dark and allows tea to remain green. In the 15th century, Oolong tea, where the tea leaves were allowed to partially ferment before pan-frying, was developed. Western taste, however, preferred the fully oxidized black tea, and the leaves were allowed to ferment further. Yellow tea was an accidental discovery in the production of green tea during the Ming dynasty, when apparently sloppy practices allowed the leaves to turn yellow, but yielded a different flavour as a result.

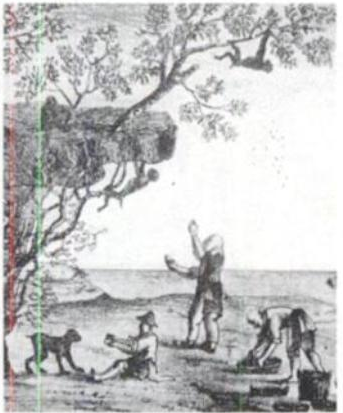

Illustration of the legend of monkeys harvesting tea

Tea production in China, historically, was a laborious process, conducted in distant and often poorly accessible regions. This led to the rise of many apocryphal stories and legends surrounding the harvesting process. For example, one story that has been told for many years is that of a village where monkeys pick tea. According to this legend, the villagers stand below the monkeys and taunt them. The monkeys, in turn, become angry, and grab handfuls of tea leaves and throw them at the villagers. There are products sold today that claim to be harvested in this manner, but no reliable commentators have observed this firsthand, and most doubt that it happened at all. For many hundreds of years the commercially used tea tree has been, in shape, more of a bush than a tree. "Monkey picked tea" is more likely a name of certain varieties than a description of how it was obtained.

In 1391, the Ming court issued a decree that only loose tea would be accepted as a "tribute". As a result, loose tea production increased and processing techniques advanced. Soon, most tea was distributed in full-leaf, loose form and steeped in earthenware vessels.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, apart from the yum cha culture of southern China, a localised version of English tea was developed, the Hong Kong-style milk tea.

Japan : History of tea in Japan

Ancient Tea Urns used by merchants to store tea

Tea use spread to Japan about the sixth century AD.[34] Tea became a drink of the religious classes in Japan when Japanese priests and envoys, sent to China to learn about its culture, brought tea to Japan. Ancient recordings indicate the first batch of tea seeds were brought by a priest named Saichō (最澄, 767–822) in 805 and then by another named Kūkai (空海, 774–835) in 806. It became a drink of the royal classes when Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇), the Japanese emperor, encouraged the growth of tea plants. Seeds were imported from China, and cultivation in Japan began.

In 1191, the famous Zen priest Eisai (栄西, 1141–1215) brought back tea seeds to Kyoto. Some of the tea seeds were given to the priest Myoe Shonin, and became the basis for Uji tea. The oldest tea specialty book in Japan, Kissa Yōjōki (喫茶養生記, How to Stay Healthy by Drinking Tea), was written by Eisai. The two-volume book was written in 1211 after his second and last visit to China. The first sentence states, "Tea is the ultimate mental and medical remedy and has the ability to make one's life more full and complete." Eisai was also instrumental in introducing tea consumption to the warrior class, which rose to political prominence after the Heian Period.

Japanese tea ceremony

Green tea became a staple among cultured people in Japan—a brew for the gentry and the Buddhist priesthood alike. Production grew and tea became increasingly accessible, though still a privilege enjoyed mostly by the upper classes. The tea ceremony of Japan was introduced from China in the 15th century by Buddhists as a semi-religious social custom. The modern tea ceremony developed over several centuries by Zen Buddhist monks under the original guidance of the monk Sen no Rikyū (千 利休, 1522–1591). In fact, both the beverage and the ceremony surrounding it played a prominent role in feudal diplomacy.

In 1738, Soen Nagatani developed Japanese sencha (煎茶), literally roasted tea, which is an unfermented form of green tea. It is the most popular form of tea in Japan today. In 1835, Kahei Yamamoto developed gyokuro (玉露), literally jewel dew, by shading tea trees during the weeks leading up to harvesting. At the end of the Meiji period (1868–1912), machine manufacturing of green tea was introduced and began replacing handmade tea.

The first historical record documenting the offering of tea to an ancestral god describes a rite in the year 661 in which a tea offering was made to the spirit of King Suro, the founder of the Geumgwan Gaya Kingdom (42–562). Records from the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) show that tea offerings were made in Buddhist temples to the spirits of revered monks.

Darye, Korean tea ceremony

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), the royal Yi family and the aristocracy used tea for simple rites. The "Day Tea Rite" was a common daytime ceremony, whereas the "Special Tea Rite" was reserved for specific occasions. Toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, commoners joined the trend and used tea for ancestral rites, following the Chinese example based on Zhu Xi's text formalities of Family.

Stoneware was common, ceramic more frequent, mostly made in provincial kilns, with porcelain rare, imperial porcelain with dragons the rarest. The earliest kinds of tea used in tea ceremonies were heavily pressed cakes of black tea, the equivalent of aged pu-erh tea still popular in China. However, importation of tea plants by Buddhist monks brought a more delicate series of teas into Korea, and the tea ceremony. Green tea, "Jakseol(작설, 雀舌)" or "Jungno(죽로, 竹露)", is most often served. However, other teas such as "Byeoksoryeong(벽소령, 碧宵嶺)" Cheonhachun(천하춘, 天下春), Ujeon(우전, 雨前), Okcheon(옥천, 玉泉), as well as native chrysanthemum tea, persimmon leaf tea, or mugwort tea may be served at different times of the year.

Vietnam

Vietnamese green teas have been largely unknown outside of mainland Asia until the present day. Recent free-enterprise initiatives are introducing these green teas to outside countries through new export activities. Some specialty Vietnamese teas include Lotus tea and Jasmine tea. Vietnam also produces black and oolong teas in lesser quantities.

Vietnamese teas are produced in many areas that have been known for tea-house "retreats." For example, some are located amidst immense tea forests of the Lamdong highlands, where there is a community of ancient Ruong houses built at the end of the 18th century.

Portugal and Italy

Tea was first introduced to Europe by Italian traveler Giovanni Battista Ramusio, who in 1555 published Voyages and Travels, containing the first European reference to tea, which he calls "Chai Catai"; his accounts were based on second-hand reports.

Portuguese priests and merchants in the 16th century made their first contact with tea in China, at which time it was termed chá. The first Portuguese ships reached China in 1516, and in 1560 Portuguese missionary Gaspar da Cruz published the first Portuguese account of Chinese tea; in 1565 Italian missionary Louis Almeida published the first European account of tea in Japan.

Greece and Cyprus

Throughout Greece and Cyprus Greek tea (Greek τσάι or tsai) is made with cinnamon and cloves.

India : History of tea in India

A view of tea Plantations in Munnar, Kerala, India

Commercial production of tea was first introduced into India by the British, in an attempt to break the Chinese monopoly on tea. The British, "using Chinese seeds, plus Chinese planting and cultivating techniques, launched a tea industry by offering land in Assam to any European who agreed to cultivate tea for export." Tea was originally only consumed by Anglicized Indians, it was not until the 1950s that tea grew widely popular in India through a successful advertising campaign by the India Tea Board.

Prior to the British, the plant may have been used for medicinal purposes. Some cite the Sanjeevani tea plant first recorded reference of tea use in India. However, scientific studies have shown that the Sanjeevani plant is in fact a different plant and is not related to tea. The Singpho tribe and the Khamti tribe also validate that they have been consuming tea since the 12th century. However, commercial production of tea in India did not begin until the arrival of the British East India Company, at which point large tracts of land were converted for mass tea production.

The Chinese variety is used for Sikkim, Darjeeling tea, and the Assamese variety, clonal to the native to Assam, everywhere else. The British started commercial tea plantations in India and in Ceylon: "In 1824 tea plants were discovered in the hills along the frontier between Burma and Assam. The British introduced tea culture into India in 1836 and into Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1867. At first they used seeds from China, but later seeds from the clonal Assam plant were used." Only black tea was produced until recent decades.

India was the top producer of tea for nearly a century, but was displaced by China as the top tea producer in the 21st century.[40] Indian tea companies have acquired a number of iconic foreign tea enterprises including British brands Tetley and Typhoo.[40] While India is the largest consumer of tea worldwide, the per-capita consumption of tea in India remains a modest 750 grams per person every year.[40] Recently consumption of green tea has seen a great upsurge across the cities. Average growth in the consumption is assumed to be over 50%. One estimate suggest the market size has already crossed over INR 1400crore and will reach a 6000 crore in next few years.

A panoramic view of tea plantations in Munnar, Kerala, India.

Top station, 41 km (1 Hour) from Munnar, is aptly named, as it is home to some of the highest tea plantations in India. It lies on the state of Kerala and commands a panoramic view of rolling green hills.

While coffee is by far more popular, hot brewed black tea is enjoyed both with meals and as a refreshment by much of the population. Similarly, iced tea is consumed throughout. In the Southern states sweet tea, sweetened with large amounts of sugar or an artificial sweetener and chilled, is the fashion. Outside the South, sweet tea is sometimes found, but primarily because of cultural migration and commercialization.[citation needed]

The drinking of tea in the United States was largely influenced by the passage of the Tea Act and its subsequent protest during the American Revolution. Tea consumption sharply decreased in America during and after the Revolution, when many Americans switched from drinking tea to drinking coffee, considering tea drinking to be unpatriotic.

The American specialty tea market quadrupled in the years from 1993 to 2008, now being worth $6.8 billion a year. Similar to the trend of better coffee and better wines, this tremendous increase was partly due to consumers who choose to trade up.[citation needed] Specialty tea houses and retailers also started to pop up during this period.

Canadians were big tea drinkers from the days of British colonisation until the Second World War, when they began drinking more coffee like their American neighbors to the south. During the 1990s, Canadians begun to purchase more specialty teas instead of coffee.

A commercial tea farm has opened on Vancouver Island in British Columbia in 2010 and expects production to start in 2015.

The Aboriginal Australians drank an infusion from the plant species leptospermum (a different plant from the tea plant or camellia sinensis). Upon discovering Australia, Captain Cook noticed the aboriginal peoples drinking it and called it tea. Today the plant is referred to as the "ti tree."

Through colonisation by the British, tea was introduced to Australia. In fact, tea was aboard the First Fleet in 1788. Tea is a large part of modern Australian culture due to its British origins. Australians drink tea and have afternoon tea and morning tea much the way the British do. Additionally, due to Australia's climate, tea is able to be grown and produced in northern Australia. In 2000, Australia consumed 14,000 tonnes of tea annually. Tea production in Australia remains very small and is primarily in northern New South Wales and Queensland. Most tea produced in Australia is black tea, although there are small quantities of green tea produced in the Alpine Valleys region of Victoria.

In 1884, the Cutten brothers established the first commercial tea plantation in Australia in Bingil Bay in northern Queensland. In 1883, Alfred Bushell opened the first tea shop in Australia in present-day Queensland. In 1899, Bushell's sons moved the enterprise to Sydney and began selling tea commercially, founding Australia's first commercial tea seller Bushell's Company.

Sri Lanka : Tea production in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is renowned for its high quality tea and as the fourth biggest tea producing country globally, after China, India and Kenya, and has a production share of 9% in the international sphere. The total extent of land under tea cultivation has been assessed at approximately 187,309 hectares.

Tea Garden in Sri Lanka

The plantations started by the British were initially taken over by the government in the 1960s, but have been privatized and are now run by 'plantation companies' which own a few 'estates' or tea plantations each.

Ceylon tea is divided into 3 groups as Upcountry, Mid country and Low country tea based on the geography of the land on which it is grown.

Africa and South America have seen greatly increased tea production in recent decades, the great majority for export to Europe and North America respectively, produced on large estates, often owned by tea companies from the export markets. Almost all production is of basic mass-market teas, processed by the Crush, Tear, Curl method. Kenya is now the third largest global producer (figures below), after China and India, and is now the largest exporter of tea to the United Kingdom. There is also a great consumption of tea in Chile. In South Africa, the non-Camellia sinensis beverage rooibos is popular. In South America yerba mate is a popular infused beverage. The only European plantation is Chá Gorreana, located in Ribeira Grande, São Miguel island, Azores (Portugal).

In South America, the tea production in Brazil has strong roots due to the country's origins in Portugal, the strong presence of Japanese immigrants and also because of the influences of their neighbor's yerba mate culture. Brazil had a big tea production until the 80s, but it has weakened in the past decades. Right now, there's only a few families trying to reorganize the tea production in the Registro, São Paulo, facing strong competition against the coffee companies.

More Details TEA

Upvote & Follow @gmbabu

Tea is my favourite beverage too

thanks

And also, Tea is my favorite beverage too.

Little story about tea in my village

https://steemit.com/indonesia/@gayocoffeefarm/the-tea-crops-in-dataran-tinggi-gayo-tanaman-teh-di-dataran-tinggi-gayo