Buprenorphine for Narcotic (Opioid) Addiction

Despite these headlines, the opioid crisis isn't an issue that is unique to this administration, or the last one for that matter. After pain was added as the 5th vital sign by the AMA in 1996, pharmaceutical companies like Purdue, the maker of Oxycontin, used this opportunity to suggest that stronger, long-acting narcotic products were appropriate in patient groups that are considered by many providers today to be inappropriate. Looser prescribing of high dose opioids increased steadily from that point and eventually devolved into a full blown crisis in the early 2000s. If you are interested in more information on this topic take a look at American Pain by John Temple. This is a very detailed account of what a pill mill operated like, taken from a convicted operator of one of the most prolific pill mills in the USA.

That, however, will be a discussion for another day. Today I want to address the science behind one of the best tools we have in treating opioid addiction today: buprenorphine, also known as Subutex (or Suboxone when combined with naloxone). This drug often gets a bad name, for no good reason, and I want to do my part to educate the public about it. For years, the only treatment option was methadone, delivered at a clinic setting, which meant the patient needed to go in for each dose. Because methadone has a long duration in the body, the patient could usually come in every 2-3 days, but this is still a major inconvenience.

Can you imagine having to schedule your life around methadone as a recovering addict?

Buprenorphine was the product of years of drug development and when it was finally approved shortly after came the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA2000) which greatly improved access to treatment in the USA. Patients no longer needed to go to a clinic every few days, but could get up to 30 days of medication and take it according to the directions at home. So what makes this different than methadone? Let's learn about that now.

I've worked around these things for years and they smell like orange candy, although the people who have to take them under their tongues daily will tell you the taste makes you nauseous after years of continual use. So what is in these magical orange candies that can keep people from using oxycodone or heroin? First a little background on the chemical structure of some other opioids...

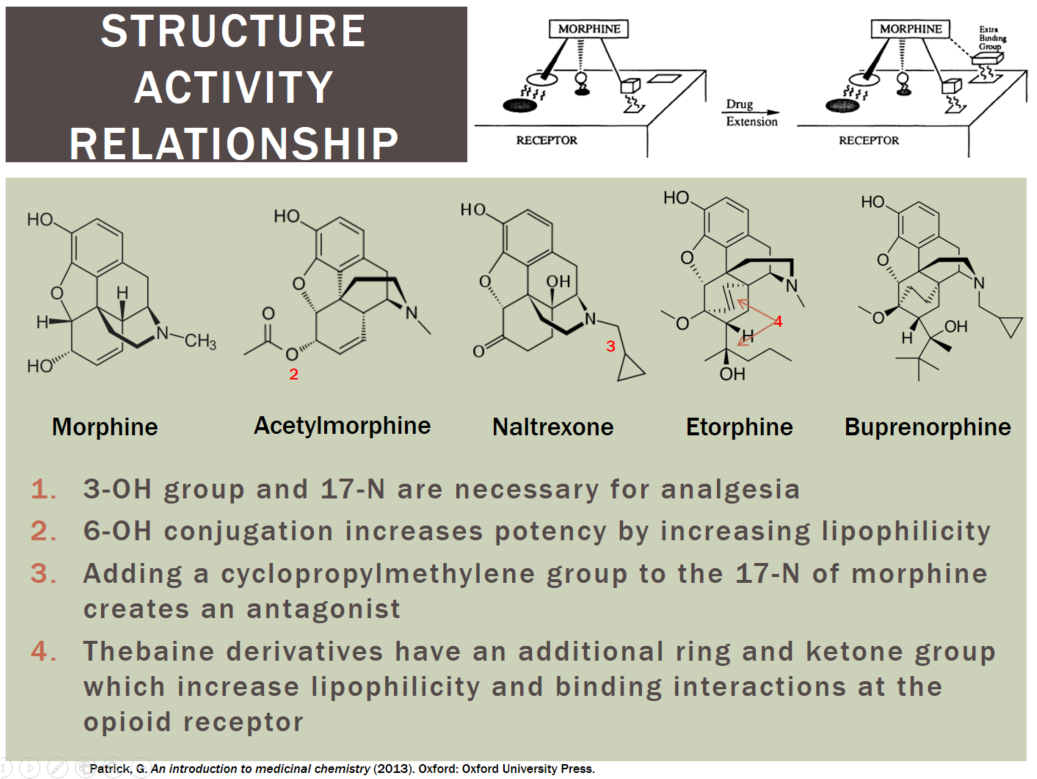

This image may be a little much for those of you who don't have a basis in chemistry, but essentially what it shows is that over years of developing new derivatives of morphine, we finally arrived at buprenorphine. From this image it is important to recognize several characteristics of buprenorphine.

1). It has a much stronger binding affinity for the opioid receptor than any commonly abused opioid. (Due to number 4 from the image)

It is therefore able to displace those drugs if they are present in the system and it is administered later. If it is being taken regularly for maintenance and the patient takes another drug of abuse like heroin, the buprenorphine will not be displaced by the heroin.

2). It is a partial agonist of the opioid receptor (Due to number 3 from the image)

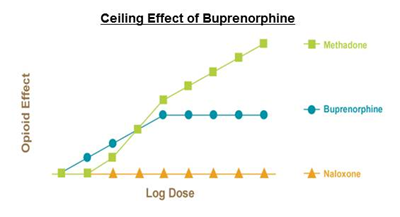

It is therefore able to give the person using the drug some reinforcement to take the drug, but it has a ceiling built in that prevents overdose from occurring. Think of it as a restrictor plate. Instead of being able to turn the dial all the way up (to the point of respiratory depression), the drug can only go to a 5 or 6.

The final piece that was added to silence the opponents of this medication was naloxone. Naloxone is a derivative of naltrexone (from the image above). Both drugs are reversal agents for opioids and opioid overdose. You may be wondering, "Why would you want to put a reversal agent together with an opioid?" and that is an excellent question. The answer lies in pharmacokinetics, or how the drugs get delivered to the body. Naloxone is very poorly absorbed when taken sublingually (under the tongue) and swallowed, on the order of 1-3%. This is not enough to have an effect on the buprenorphine. If the patient decides to dissolve the medicine in water and inject it, however, it becomes 100% available to their opioid receptors. There is a caveat of course... buprenorphine is unlikely to be displaced by naloxone and therefore it would have little effect. The real purpose is to prevent diversion to other patients who might be using other types of opioids. They would experience withdrawal immediately upon injection if they are using heroin, oxycodone, etc.

FYI This is my first original content to the community.

I have a background in health, science, and pharmaceuticals.

I'm happy to answer questions or write on other topics if there is interest.

Congratulations @bru! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPIt's fascinating what our scientists can do. I always have interest in reading educational posts, so if you have time please do!

I will try to put something new out when the mood strikes me. Thanks for the upgoat!

@oregonpop got you a $1.88 @minnowbooster upgoat, nice! (Image: pixabay.com)

Want a boost? Click here to read more!