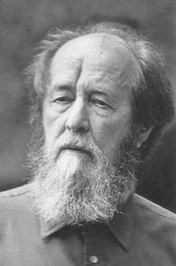

Solzhenitsyn the banned author

Of the six stories in six time frames that are cut into small pieces and deftly dovetailed in “Cloud Atlas,” one—that of the present day—is like a shield to render the movie critic-proof: a plotline pivoting on an author who murders, to public acclaim, a critic who panned his new book. I’ve written here before about critical responsibility and the moral obligation to compensate, in thought, for the disproportion between the filmmaker’s lengthy labors and the critic’s quickly typed response. I’ll admit that I experienced “Cloud Atlas” mainly as the motion-picture equivalent of being cornered at a noisy party by three filmmakers expounding at length—with animated gestures and gusty yet sincere vehemence—on their philosophy of life, and I would argue that it’s worthwhile to figure out what that philosophy is. That’s where the surprises are to be found, and that’s where the filmmakers (Lana Wachowski, Andy Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer) snuffed out most of the project’s potential for cinematic invention.

The movie’s six episodes are set in six time periods: in 1849, an American doctor helps a slave escape; in 1936, a young British composer seeks to free himself from the authority of an older one; in 1973, an American journalist seeks to reveal the dangers of a San Francisco nuclear power plant; in 2012, a British editor seeks to escape from a nursing home; in 2144, a clone-slave, or “replicant,” in Neo Seoul flees captivity to expose the truth of that society; and in a distant post-apocalyptic future, that replicant’s message, a sort of gospel for a persecuted sect, inspires the survival of civilized humanity on a distant planet.

If a prime virtue of direction is the use of images and sounds to conjure an experience of something beyond the substance of the script, only one of the six episodes has any substantial merit: the one set in Neo Seoul in 2144, plus a few brief scenes in the post-apocalyptic one, a sole moment set in 1849 (an exhilarating swing by rope from a mast) and another from 1973 (a view from inside a car as it flies off a bridge into the bay). Otherwise, it’s a painful movie to look at, directed mostly at a television level. In terms of visual style, it’s five-sixths a nullity, a non-experience—and, at a hundred and seventy-two minutes, that’s a whole lot of nothing.

Having not paid attention to the coverage, I had no idea how the directorial duties were divided up, and assumed—wrongly, as it turns out—that they weren’t divided at all. Actually, Lana Wachowski and Larry Wachowski directed the two futuristic episodes and the one from the most distant past (1849) and Tykwer took on the two twentieth-century segments (1936, 1973) and the one set in the present day—and that division shows in the results. Predictably, the Wachowskis made much of C.G.I. in devising the futuristic city. It’s their sweet spot, and they hit it, a few moments and a few shots at a time.

Just as directors’ statements about their intentions have no special validity for a viewer’s experience of a movie, the theme that’s stated in a movie’s script is often not the most important or most significant one. Taking the “Cloud Atlas” script at its word would wrongly suggest that the movie is mainly about interconnectedness, about the unsuspected and inextricable bond that causally links actions—and people—over time. The text suggests something of moral butterfly effect—the idea that a tiny action taken today may be the principal cause of great or grave results in the future. The action itself, and the way its sections both connect and reflect each other, indicate that the movie’s key doctrine is the repetition of history. And the main template that the filmmakers put forth concerns the abuse of power and the resistance to abusive power, or, as is said in the movie, the quest for freedom The old editor of the current day, played by Jim Broadbent, says “x‘Freedom!’ is the fatuous jingle of our civilization, but only those deprived of it have the barest inkling re: what the stuff actually is,” and the revolutionary replicant, Sonmi-451 (echo of Bradbury) quotes the then-banned author Solzhenitsyn. In repeating itself, history becomes cyclical—the future gospel of kindness that she preaches, in the face of a cruel neo-pagan religion, suggests the second coming of Christianity.

The tastelessness of having Jim Sturgess appear as a Korean, and Halle Berry and Doona Bae as Caucasians—and, over-all, the “Where’s Waldo?” game of seeing through the guises in which famous actors seem to turn up—is no more offensive than the movie’s dunningly dull images that cry out to be accepted for their presumptive importance, their message to humanity, the ideas (such as they are) that the images transmit and fit all-too-tightly. The polymorphic role-playing implies that the time in which one lives and the ethnic identity one is born with are mere incidentals. For all the malleability and moral pressure of free will that the tied-together stories suggest, the movie’s real message is the eternity of the present day: all the people there are now are essentially the people who always were and who always will be. The effect is like that of metempsychosis, of reincarnated souls, but the metaphysical dimension is replaced by a biological one. The subject of the movie is wiring, and, specifically, hard-wired information. That’s why it’s so significant that, when Sonmi-451 speaks to her liberator, she says, “Knowledge is a mirror” thanks to which, she says, “I can see who I am.” The definition of an image isn’t visual; it’s data (like, of course, the very images that the Wachowskis create).

The creators of “The Matrix,” after all, have a sense of digitally malleable realities, and the vision that they realize in “Cloud Atlas” is also one of virtual possibilities. But whereas those of “The Matrix” were essentially audiovisual, those of “Cloud Atlas” are informational: the movie’s underlying argument is that all of human existence is data, and that, if you type just the right terms into the cosmic search engine, you’ll get slices of life that make for deeply meaningful cross-sections of existence. It’s as if they’ve come to see deep meaning in the weird successions of links that Internt searches turn up. It’s a commonplace that art teaches us about the lives of people who lived in times and places utterly different from our own; the ultimate effect of “Cloud Atlas” reverses that equation, terrifyingly. All human ages and types seem to issue from, and to resemble, the most stultifying banalities that Hollywood can issue.

“Cloud Atlas” is hardly different from the first “Atlas Shrugged” movie (haven’t yet seen the second), except for one thing: whatever aesthetic redemption such message movies may offer would be in the realm of excess, whether of histrionic frenzy or of chilled uniformity. “Cloud Atlas” offers neither: the three directors’ professional moderation, the conventional naturalism of what usually passes for good acting and of straightforward storytelling, insures that the movie looks nothing like the dogmatic screed that it is. In the Neo Seoul of 2144, the reigning oppressive power is called the Unanimity, but there’s nothing so unanimous as three filmmakers who know exactly what they want to say and make sure that their film says it.

One of the prevailing memes about the movie regards its audacity and the importance of its high-budget production (it was made with a hundred million dollars of independent financing). As Anne Thompson tweeted last week, “I’m sorry cloud atlas rejection will make it tougher for risktaking in future.” In other words, its success or failure will influence studios to make either more or fewer of such movies. But what kind of movie is “Cloud Atlas” and what makes it particularly risky to produce and distribute? Sure, it’s got six stories rather than one; sure, it thrusts a philosophy of sorts front and center. The problem is that it’s not audacious enough; the story-telling within each episode is utterly conventional, familiar; the image-making is for the most part unoriginal; the acting is skillful but nothing new. And there isn’t much on-screen that shows great expense and great attention to décor, to the full and deep creation of vast worlds. And that’s something that might have taken a lot more money but might also have been done with less money—but, in any case, would certainly have taken a lot more imagination, more and better ideas.

Congratulations @momet11! You received a personal award!

Happy Birthday! - You are on the Steem blockchain for 1 year!

Click here to view your Board

Congratulations @momet11! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!