The Jeffersonian Solution: An Independent Approach To Freedom

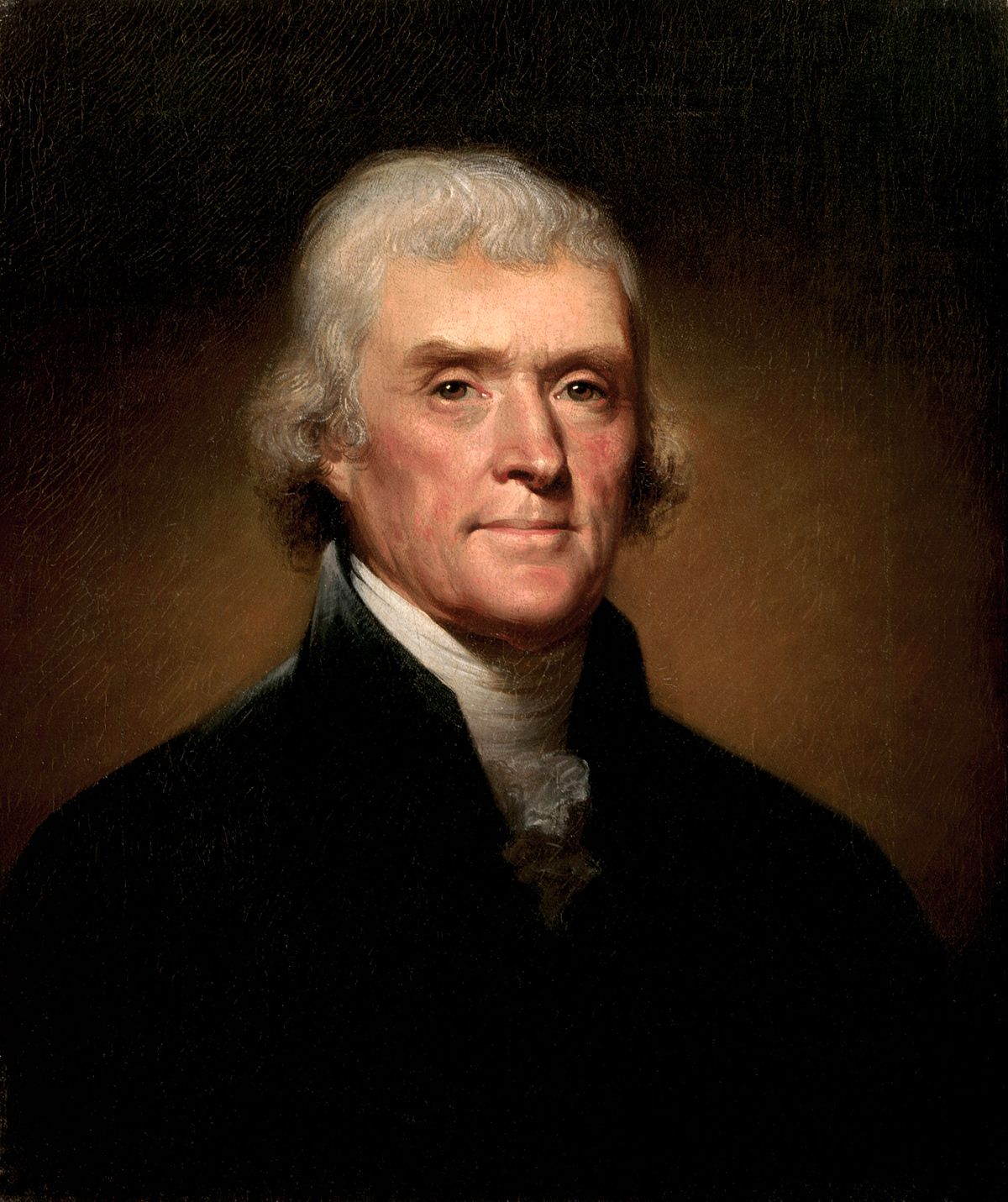

Thomas Jefferson

This short opinion piece was written by me and submitted to the NY Times editorial page back in 2009. It was not published, but that is understandable. The Jeffersonian Solution, once so universally understood, is now so alien to modern Americans that it will never be taken seriously by the mainstream. Nevertheless, Jefferson understood the nature of freedom, and his wisdom in this regard is worth considering. For some, it is worth pursuing on an individual level...

By: Herrick Kimball

The original strength of our American republic was found in the ability to supply our own needs. That is the very definition of independence. We provided our own form of government, our own energy resources, our own manufacturing, and we grew an overabundance of our own food. We were a self-sufficient nation.

This condition of national independence was the natural outgrowth of America’s many independent farming communities. The vast majority of early Americans lived on small farms and homesteads, providing their own food, shelter, clothing, and most other necessities from their own land. Today, however, less than 2% of our population is involved in the work of agriculture, and that agriculture has greatly changed. Now it’s called agribusiness and it is dependent on enormous, unsustainable imports of foreign oil. Subsistence farms have become rare as hen’s teeth.

Thomas Jefferson, primary author of the Declaration of Independence, believed that a citizenry which worked the land, drawing sustenance directly from the earth, was the surest support of our free and independent nation; that such agrarianism engendered a healthy civic virtue. After all, self-reliant people don’t need or want government handouts, and they are not easily manipulated by scheming politicians.

In his book, Notes on Virginia, Jefferson made a remarkably prescient statement:

[Note: "venality" means corruption]

Slowly and surely, over the course of two centuries that which was abundantly clear to Jefferson has become a truth no longer self evident. Once thrifty, resourceful and largely self-reliant on their own land, Americans are now mostly crowded into cities and suburbs, playing their specialized roles in the corporate-industrial drama, dependent on a global network of industrial providers and so many forms of government subsidy. We have become the land of the dependent and the home of the helpless.

It is no coincidence, then, that America as a whole has evolved into a needy nation, a dependent nation, a debtor nation and, as a result, an increasingly weaker nation.

Industrialization has brought us to servitude. First, unwary Americans willingly exchanged their independence bit by bit for tempting morsels of comfort and ease. Further along the path, as the germ of virtue was suffocated and venality dominated, much more personal freedom was (and is) taken by the centralized powers of the State in the name of supposed benevolence, or to protect us all from a host of spectral boogiemen. We’ve come to the point in America where individual freedom is little more than a lovely but quaint phantasm.

So it is that the forces of industrialism, allied with government and all manner of techno-wizardry, are advancing on numerous fronts, implementing with scientific deviousness the goal of ever more centralized control over We its Subjects. Unprecedented designs of ambition are circling overhead.

This is what happens when a civilization, blinded by generations of industrial and technological hubris, separates from its agrarian roots. In a sad paradoxical twist, Americans have come to love the conditions of their modern subservience. This is not what the Founders had in mind. It is not the way free men live.

Popular opinion dictates that organized political action alone will bring the changes that America needs. But this is a false hope. Fundamental and significant change will never come from government. It will come only when American citizens change themselves. We must break away from the various industrial-world dependencies and reconnect to the agrarian wellspring. Americans must return to the land, re-embrace simplicity, self-sufficiency, independence, and personal responsibility—one person, one family, at a time.

The good news is that this is already happening to a small degree. A new American yeomanry of landed smallholders is rolling up its sleeves and working in earnest to take care of itself, apart from industrial and government dependencies. I am among them.

My family lives on 1.5 rural acres in the Finger Lakes Region of New York state. I built my small but comfortable home with my own hands. We heat with a basic wood stove. We raise chickens for meat and eggs. Our freezers are packed with vegetables from our garden and venison harvested from the woods and fields around us. There are bushels of homegrown potatoes and onions in the basement. Our pantry shelves are lined with jars of home-canned applesauce, tomatoes, pickles, green beans, and so much more. We have little money, but no debt.

If, as Jefferson so rightly warned, dependence begets subservience, then it follows that independence begets freedom. This is true on a national and personal level. The path back to individual liberty begins with awareness, determination, and a small piece of land. The rural sections of America are vast, much of the land is inexpensive, and it is full of productive potential. If husbanded with care, the soil will yield an abundance. The land is calling freedom-loving Americans back to itself and forward to a better reality. Do you hear it?

Congratulations @farmbeet! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honnor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPBy upvoting this notification, you can help all Steemit users. Learn how here!

I often tell students that probably the most difficult aspect of learning American history is not learning dates, or names, or that people simply used different technology, it's in understanding that people's worldview was often VERY different from our own. I think you've really hit something here; something that we see in some early 19th century (and possibly 18th century; I'm not as familiar with it) literature: the idea of the "free and independent" person. I don't romanticize the past at all. Life and work on isolated farms was often backbreaking and intellectually deadening, and sometimes people died like flies. However, when the majority of Americans gave up land ownership and some measure of food-independence for the shaky security of a paycheck it was the start of a different worldview-maybe not a new one because many people in the "old countries" had been dependent in one way or another- but it really altered worldview of later generations of Americans.