Bully Acre

This short paragraph brings to an end the episode known as The Battery at the Gate, which takes up the last ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. In the preceding paragraphs HCE suffered an assault at the hands of a travelling salesman―or was it a reporter for a German newspaper?―who pegged a few stones at his tavern before slouching off in the direction of the deaf-and-dumb institutes in Cabra and Glasnevin. Is it significant that Glasnevin is also the site of Dublin’s largest cemetery? In Hosty’s Rann the dead were described as deaf and dumb:

And we’ll bury him down in Oxmanstown

Along with the devil and Danes(Chorus) With the deaf and dumb Danes,

And all their remains.

RFW 038.14–17

By the end of this chapter, HCE, who has been consistently identified in this chapter with his own attacker, will be dead. His chambered cairns are briefly described in the next paragraph, though his real burial will take place in the following chapter.

The final four paragraphs of this chapter were additions to the first draft, which concluded with the bullocky proceeding in the direction of the deaf & dumb institute. When an early draft of the chapter was published in transition in June 1927, only the second and fourth of these paragraphs had been written. The third paragraph was added in the early 1930s, when Joyce was preparing copy of Book I for the printers at Faber and Faber. The first paragraph, however, was a very late addition to the second set of galley proofs―dated to May 1938 by Rose & O’Hanlon.

The only alteration Joyce made to his first draft of this paragraph was the inclusion of the parenthetical clause if old Nestor Alexis would wink the worth for us. The meaning is fairly transparent: with the exit of the Bullocky, the Battery at the Gate and the siege of HCE’s refuge finally came to an end.

Sieges

Joyce has packed several historical sieges into this brief paragraph. Throughout the Battery at the Gate, HCE was besieged in a succession of refuges.

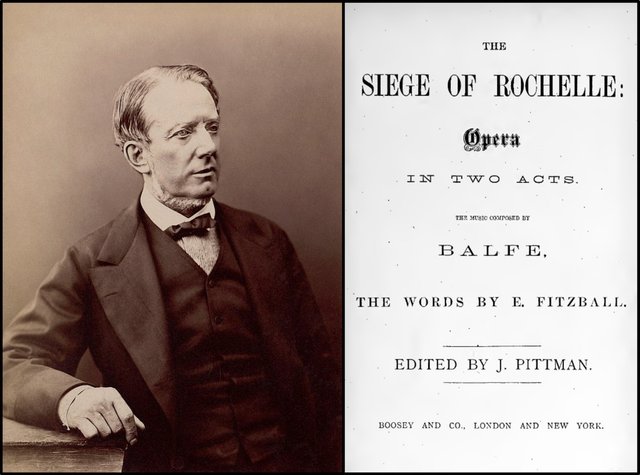

- rochelly Michael William Balfe’s opera The Siege of Rochelle. This siege in 1627–28 forms the backdrop to Dumas’ novel The Three Musketeers. Balfe’s opera is based on another novel by Madame de Genlis. As John Gordon notes, the French: roche, rock is also relevant. HCE’s attacker was a pegger of stones.

exetur exit, and Latin: exitus, exit, departure. In both English (medical) and Latin (figurative) exitus can also mean death. There is probably also an allusion to Exeter in Devon, which was besieged several times in its history:

- 630 (approximately) by Penda of Mercia

- 893 by the Danes

- 1068 by William the Conqueror

- 1549 during the Prayer Book Rebellion

- 1643 by the Royalists during the English Civil War

- 1645–46 by the Parliamentarians during the English Civil War

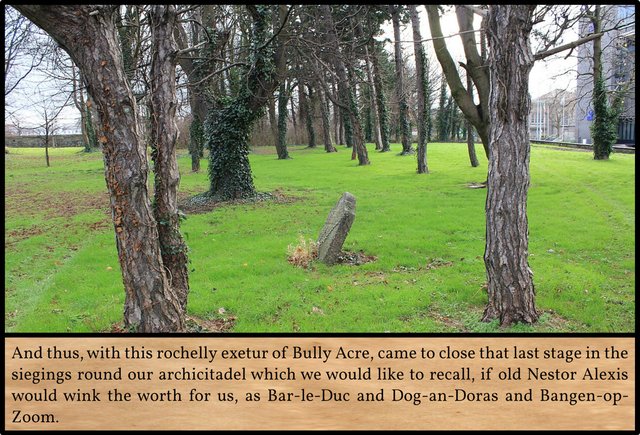

Bully Acre Bully’s Acre in Kilmainham is one of Dublin’s oldest cemeteries, possibly dating back to the 7th century. It was finally closed in 1832, when thousands of victim’s of that year’s cholera epidemic were buried there. There is also an allusion to the Palestinian city of Acre, which was besieged by the Crusaders in 1104 and by Napoleon in 1799. And, of course, Clontarf, the site in 1014 of one of Ireland’s bloodiest and most notable battles, takes its name from the Irish: cluain tarbh, bulls’ meadow. Finally, Bully Acre recalls the bullocky of the preceding paragraph.

stage the theatrical (and operatic) meaning is relevant.

siegings besiegings. German: siegen, to triumph. FWEET also glosses this as German: sie ging, she went, though I fail to see how this is relevant. Who is she? FWEET’s proceedings, however, does make sense.

recall rename. We would like to rename Dublin Bar-le-Duc and Dog-an-Doras and Bangen-op-Zoom.

old Nestor Alexis In Homer’s Iliad, Nestor, the King of Pylos, is the eldest of the Achaian leaders. The phrase old Nestor, occurs a number of times in the epic poem (eg 11:637). Nestor is also the second episode of Ulysses, in which Stephen teaches history to the boys, before discussing history with his elderly employer Mr Deasy. Nestor’s relevance here can only be his association with the Siege of Troy. Adaline Glasheen questions the allusion (Glasheen 205). I have no idea who Alexis refers to. In A Classical Lexicon to Finnegans Wake, Brendan O’Hehir glosses it as name of a shepherd in Virgil’s 2nd Eclogue, though I fail to see the relevance (O’Hehir 47). In Ancient Greek, the name means helper or defender.

wink the worth for us Wynkyn de Worde was an Alsatian-born printer and publisher, who worked with William Caxton in London. In Ulysses, Deasy (old Nestor) gets Stephen to arrange for the printing of his letter on foot-and-mouth disease in the Irish newspapers, in the hopes of getting the word out.

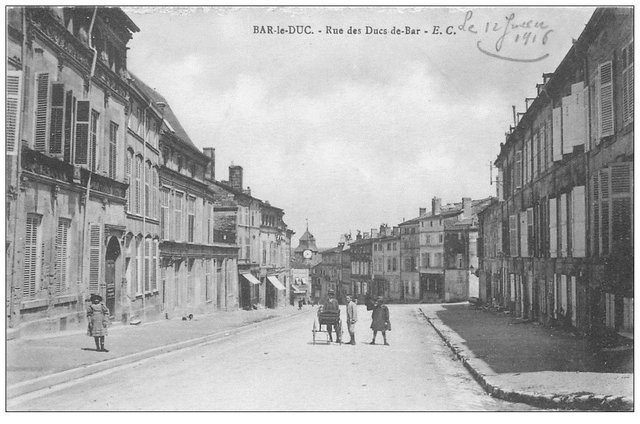

Bar-le-Duc A town in northeastern France. During the siege of Verdun (Battle of Verdun in 1916), Bar-le-Duc served as the staging area or assembly point for the besieged city’s essential supplies.

Dog-an-Doras Irish: deoch an dorais, parting drink (literally: the drink of the door). The wolf is at the door generally means that one is afflicted with hunger or poverty, which may be relevant here.

Bangen-op-Zoom Bergen-op-Zoom, a town in the Netherlands. It was frequently besieged. HCE’s besieger is banging on the door.

Concerning the last three elements, John Gordon comments:

73.24–-5: “Bar-le-Duc and Dog-an-Doras and Bangen-op-Zoom:” I suggest that these three proposed names all contain elements adding up to: bar the door that someone is banging on. McHugh notes that Bar-le-Duc was the “staging area for the Battle of Verdun,” and the famous line coming out of that battle was “Ils ne passeront pas” [They shall not pass]. Medals and posters celebrating the battle sometimes show a French man or woman (Joan of Arc) blocking a door, gate, passageway, etc. ―Gordon 73.24–5

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Brendan O’Hehir, A Classical Lexicon for Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

Image Credits

- Bully’s Acre: © Deitel55 (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Michael William Balfe: Atelier Nadar (photographers), Adam Cuerden (restorer), Public Domain

- Bar-le-Duc in 1916: Edmond Cailteux, Postcard, Public Domain

- The Marketplace in Bergen-op-Zoom: Abel Grimmer (artist, attributed), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Public Domain

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog