As the lion in our teargarten

The fourth chapter of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake opens where the previous chapter left off. HCE is imprisoned, asleep or dead―in the dreamworld of Finnegans Wake there is no real difference between the three. In each case he has been removed―whether permanently or temporarily―from the world of the living. The opening paragraph of this chapter can be read from each of these perspectives.

Finnegans Wake Notes gives the following summary of this page:

Page 75 captures the richly layered consciousness of HCE (Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker) as he reflects on his downfall, a recurring theme in Finnegans Wake. The text oscillates between dreamlike recollection and mythic representation, intertwining Hiberno-English with echoes of Irish history, mythology, and culture. Joyce uses dense wordplay, mythical references, and an experimental narrative style to explore themes of guilt, legacy, and redemption.

Joseph Campbell & Henry Morton Robinson were also surely right when they wrote in A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake:

One gets the impression that HCE’s trial and incarceration are intended to symbolize the crucifixion and entombment of Christ. ―Campbell & Robinson 79

This is confirmed by the phrase three and a hellof hours’ agony of silence, which refers to the Devotions of the Three Hours’ Agony in honour of Christ on the Cross. According to tradition, Christ descended into Hell when he died. Another incarcerated Irishman is also alluded to here. Oscar Wilde lived for only three-and-a-half years after his release from prison (from 19 May 1897 to 25 November 1900). He is referenced by the very next words (see below).

First-Draft Version

As usual, a good place to begin our analysis is with the first draft of this passage, as recorded by David Hayman:

With deepseeing insight he may have prayed in silence that his wordwounder might become the first of a long dynasty[,] his cherished idea being the formation, as in more favoured climes, of a truly criminal class, thereby eliminating much general delinquency from all classes & masses. ―Hayman 75

As we have seen, The Humphriad II concluded with HCE seeking refuge from an attacker, who had first pegged stones at his tavern, before resorting to name-calling when HCE wouldn’t come out and face him like a man. This attacker represents not only the Cad with a Pipe but also HCE’s own sons―in both cases an Oedipus to HCE’s Laius. This is why HCE cherishes the idea that his wordwounder might become the first of a long dynasty. But why does does he hope that his descendants will be of a truly criminal class, and why does he think that this will eliminate delinquency in general from all of society? What exactly is Joyce getting at here? The following note is relevant:

no crim. class in Ireland / create it! HCE ―FW VI.B.11:136b

I can only assume that HCE has decided that he might as well be hung for a sheep as for a lamb. If his fellow citizens are going to charge him with every crime under the sun, he might as well go the whole hog and provide Ireland with something it currently lacks: a genuine criminal class. And if his descendants come to monopolize crime in Ireland, there will be nothing left for the rest of society to do in this regard.

- deepseeing insight This may be glossed as deep sea, introducing a maritime theme that runs through this paragraph.

In revising this passage, Joyce took the phrase as in more favoured climes as an opportunity to transport his reader to the banks of the Nile and to Armenia.

Armenian

In Finnegans Wake, Joyce always seems to associate Armenia with the Garden of Eden.

teargarten (Tiergarten is German for zoo, meaning literally animal-garden) conjures up an image of the Garden of Eden. Noah’s Ark, a floating zoo that came to rest in the mountains of Armenia, is also relevant, and plays up the maritime theme of this paragraph. As Armenia is one of the places where Biblical commentators have sought Eden, it is not surprising that there is a small foliation of Armenian terms in the opening lines of this paragraph:

Ariuz aryuz [առյուծ (aṙyuc)] : lion. Sirius may also be present, and perhaps Leo the Lion. HCE looking into the future is like an astrologer, casting his horoscape.

Arioun aryun [արյուն] : blood. Is Orion also implied, to match the nearby Sirius? Arion was a legendary Greek poet who invented the Dionysiac dithyramb, from which Greek tragedy evolved. Herodotus recounts how Arion was once saved from drowning by dolphins―the maritime theme again.

Boghas Bôghos [Պօղոս (Pōġos)] : Paul―St Paul, who was once shipwrecked. And Pegasus, to continue the astrological theme. Bacchus (Dionysius) continues the Greek tragedy theme. He once transformed himself into a lion.

baregams barekam [բարեկամ] : friend, neighbour. There is also an obvious allusion to Issy’s bare legs. The slang term gams probably derives from the French: gambe, leg (an old spelling of the modern jambe). John Gordon considers the American use of the term to refer to a woman’s sexy legs as relevant. This usage dates to the 1920s.

Marmarazalles marmnagan [մարմնական (marmnakan)] : corporeal, bodily. Rose & O’Hanlon comment that in the context Joyce means bodies. The phrase Marmarazalles from Marmeniere echoes the title of the song Mademoiselle from Armentièrres, which was popular among British soldiers during World War I. Armentièrres is a French town on the Belgian border. The town was repeatedly shelled during the war and was the site of an important battle in October 1914. Marmeniere also conceals Armenia. Roland McHugh’s Annotations also suggests the Ancient Greek μάρμαρος, marble, but the Sea of Marmara is surely more relevant.

ouxtrador ukhdavor [ուկհդավոր] : pilgrim. This word was omitted from the first edition, but restored by Rose & O’Hanlon in 2010.

Nile

Egypt and the Nile are only briefly alluded to:

German Tiergarten, zoo. Dublin Zoo is located in Phoenix Park, which is adjacent to the Mullingar House. Because the lion is a captive, he is sad: hence, his tears are genuine, unlike the crocodile tears one may encounter by the Nile. In Phoenix Park, the Tea Rooms are next to the zoo. Rose & O’Hanlon assume that the German implies that Berlin Zoo is meant. There is also an allusion to Lyons’ Tea Rooms, a chain of restaurants that also doubled as public lavatories for women.

nenuphars white water lilies (Nymphaea alba). The allusion to both lilies and nymphs identifies these nenuphars with Issy. The nenuphar itself is not native to Egypt, but its name comes from the Sanskrit word for blue, nīlotpala (blue lotus), which evokes the River Nile. The etymology of Nile is disputed, but one hypothesis traces it to the same Sanskrit root. Another species of the same genus, Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea or Sacred Blue Lily of the Nile, is native to Egypt. It is also known as the Egyptian lotus.

Isis is also hinted at in line 5, as we shall shortly see.

In the Dutch Brig

Most of the foreign terms in this paragraph are taken from Dutch, not Armenian. John Gordon suggests that the high incidence of Dutch in the early pages of this chapter reflects the watery or underwater setting (John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog 75.8). Alternatively, there may be an allusion to the British naval expression Dutch brig, which refers to the prison cells on board a vessel. HCE is not at sea, but he is in the brig. As we have seen, however, there is a maritime theme running through these lines.

tots wearsense tot weerziens : goodbye, so long. A tot is also a small amount of liquor, especially rum. The following word, full is also an obsolete term for a goblet (Oxford English Dictionary 4:588). The watery theme has made HCE thirsty (theirs to stay).

naggin in twentyg negen en twintig : twenty-nine. A naggin is a small measure of whiskey. The term is used especially in Dublin (elsewhere the usual form is noggin). Twenty-nine is, of course, Issy’s number, being the number of days in her birth month, February. Issy was born in a leap year.

sigilposted postzegel : postage stamp. This and the following item must allude to ALP’s Letter, though I can’t say that I understand what Joyce is getting at. The Sihlpost is Zurich’s general post office, which was constructed between 1927 and 1929:

what wat : something

brievingbust brievenbus : post box, mailbox (both public and private). And Issy’s heaving bust? Grieving breast?

stil : silent, quiet. The first edition had stil, but Rose & O’Hanlon emended this to still in The Restored Finnegans Wake, which loses the Dutch allusion.

Fooi fooi : tip, gratuity. Also Foei! : Fie!

chamermissies kamermeisje : chamber maid. Nora Barnacle was employed as a chambermaid at Finn’s Hotel when she and Joyce first became acquainted. Tipping Issy for her sexual favours makes a whore of her. Although Finn’s Hotel is in central Dublin, it appears that Joyce initially considered transferring its name to the Mullingar House (originally called the Mullingar Hotel) in Chapelizod and making it the title of his novel. There might also be an allusion to Chamber Music, the title of Joyce’s early collection of lyrics. The title jokingly refers to the sound of a woman urinating into a chamber pot―echoing the allusion above to Lyons’ Tea Rooms.

Zeepyzoepy zeepsop : soapsuds. Also zoep : soap.

larcenlads laarzen : boots. Presumably Shem & Shaun as larcens. Also laarzenlade : boot-drawer, boot-shelf.

Zijnzijn zijnzijn zijn : to be and his. This echoic motif is always associated with HCE’s coffin, which will take centre stage on the following page.

we moest ons hasten selves we moesten ons haastten : we had to hurry. Also zelfs, even (adverb).

te te : to, at

declareer declareer : declare (imperative single : first-person singular present indicative). This verb is now used of goods one is declaring to customs officials, etc.

we habben we hebben : we have

upseek opzoeken : to seek out, look up, call on

a bitty een beetje : a little bit

door door : through, by

courants courant : newspaper (the modern form is krant)

want : because, for, as

’t ’t : the or it (a contraction of het)

kingbilly bil : buttock

kunt ye neat kunt u niet?, kun je niet? : can't you?. Also kont, arse.

gift gift: gift, present : poison, venom

gift mey geef mij, geef me : give me

gift mey toe geef mij toe : grant me, admit to me, give in to me. Also toegift : makeweight, bonus, extra.

toe toe! : please!

bout bout : bolt, leg of animal or bird considered as a joint for the table, drumstick

peer peer : pear

saft eyballds zacht ei : soft-boiled egg

kreeponskneed ons : us, our. Creep-on-knees suggests the serpent in the Garden of Eden.

taal taal : language. To make a long tale shorter. Rose & O’Hanlon emended the first edition’s bank to lank.

Isis Unveiled

the besieged bedreamt him still and solely of those lililiths undeveiled

German besiegt : defeated

lililiths Lilith, a female demon in Jewish mythology. In rabbinic literature Lilith is depicted as Adam’s first wife before the creation of Eve. She was banished for not submitting to her husband’s authority. Here, Lilith is pluralized because she represents schizophrenic Issy. In Finnegans Wake Issy is associated with lilies, like the nenuphars of the opening line. FWEET, however, also points out that the combination of lily (a plant) and -lith (from the Greek λίθος, stone) echoes the tree/stone motif, in which Shem and Shaun combine to create Tristan (Treestone). HCE has been undone by all three of his children.

undeveiled undefiled, with perhaps a hint of devil, as Lilith is demonic. This paragraph also contains several allusions to the serpent in the Garden of Eden. The main allusion, however, is to Isis Unveiled. The Egyptian goddess Isis is another of Issy’s avatars.

Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology was the first major publication of the Russian theosophist Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891). In 1875 Blavatsy co-founded the Theospopical Society in New York with Henry Steel Olcott and William Quan Judge. Two years later she published Isis Unveiled in two volumes. Volume I, _The “Infallibility” of Modern Science, criticizes Western science and offers Hermetic teachings as an alternative path to scientific truth. Volume II, Theology, is a comparative study of all the World’s major religions, which Blavatsky believed were derived from a common source, the ancient Wisdom-Religion of Hermeticism.

In 1887 Blavatsky settled in London, where she established The Blavatsky Lodge of the Theosophical Society:

She received a stream of distinguished guests in Lansdowne Road [in Holland Park, London], including W. B. Yeats, who later compared his hostess to an old Irish peasant woman, at once holy, sad and sly. Yeats took the revival of eastern wisdom very seriously and dabbled in a wide range of esoteric ‛sciences’ including cheirosophy (palmistry), celestial dynamics (astrology), chromopathy (healing by colours) and polygraphics (a form of automatic writing). Alerted to Theosophy by Sinnett’s Esoteric Buddhism, but doubting the objective existence of the Masters, he was converted to membership by Mohini Chatterjee, who arrived in Dublin in 1885 ‛with a little bag in his hand and Marius The Epicurean in his pocket’. Mohini, who returned to Ireland in the following year to address Yeats’s recently formed Hermetic Society, told the poet that ‛Easterns’ had a quite different sense of what constitutes truthfulness from Europeans, a claim in which Yeats heard no irony, perhaps because he found ‛the young Brahmin’ seductive. ―Washington 91

A Dublin Lodge of the Theosophical Society was founded in 1886. Yeats and AE (George William Russell) became members. In Joyce’s day the lodge was located at 13 Eustace Street. The Hermetic Society held their meetings on Thursday evenings at 11–12 Dawson Street. In Ulysses Stephen Dedalus and Buck Mulligan make fun of that hermetic crowd:

―Professor Magennis was speaking to me about you, J. J. O’Molloy said to Stephen. What do you think really of that hermetic crowd, the opal hush poets: A. E. the master mystic? That Blavatsky woman started it. She was a nice old bag of tricks. ―Ulysses 135

Yogibogeybox in Dawson chambers. Isis Unveiled. Their Pali book we tried to pawn. Crosslegged under an umbrel umbershoot he thrones an Aztec logos, functioning on astral levels, their oversoul, mahamahatma. The faithful hermetists await the light, ripe for chelaship, ringroundabout him. Louis H. Victory. I. Caulfield Irwin. Lotus ladies tend them i’the eyes, their pineal glands aglow. Filled with his god he thrones, Buddha under plantain. Gulfer of souls, engulfer. Hesouls, shesouls, shoals of souls. Engulfed with wailing creecries, whirled, whirling. they bewail.

_In quintessential triviality

For years in this fleshcase a shesoul dwelt.

―Ulysses 184

Joyce also took a keen interest in the hermetic crowd and their theosophy, if only to mine it for his own literary purposes. His Trieste Library included a number of texts relevant to the subject:

Annie Besant, Une introduction à la théosophie, Publications Théosophiques, Paris (1907). In 1909 she visited Dublin and addressed the local lodge.

Annie Besant, The Path of Discipleship, Theosophical Publishing Society, London (1904)

Henry S Olcott, A Buddhist Catechism According to the Sinhalese Canon, Theosophical Publication Society, London (1886?). He too paid a visit to the Dublin lodge.

C W King (translator), Plutarch, Morals: Theosophical Essays, George Bell, London (1882)

Rudolf Steiner, Blut ist ein ganz besonderer Saft, Philosophisch-Theosophischer Verlag, Berlin (1910)

James Atherton believes that Joyce used Isis Unveiled itself and another of Blavatsky’s works, The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett―adding the comment, if only as an example of forgery. The Mahatma Letters were published in 1923 but the letters, which are addressed to A P Sinnett, were allegedly written between 1880 and 1884. Their authors were Koot Hoomi and Morya, two Masters or mahatmas who inspired the foundation of the Theosophical Society. Even before publication their authenticity was doubted. As early as 1885, the Australian psychical researcher Richard Hodgson, who had had the opportunity of examining some of the original documents for himself, was convinced that Blavatsky had penned them herself. In the context of Finnegans Wake, this makes Helena Blavatsky both Righard Pigott (the forger of the Parnell Letters) and ALP, the author of the Letter:

The ‛Mahatma Letters’ were supposed to be written by Tibetan ‛masters’ one of them was called ‛Morya’ ... They were said to be conveyed from Tibet by telekenesis or osmosis ... The recipient, A. P. Sinnett is named ... Another of Madame B.’s friends, Colonel Olcott, had a big white beard which is mentioned ... This follows the mention of a ‛sliding panel’, which is probably the one described in Who Wrote the Mahatma Letters? by H. E. and W. L. Hare ... Madame Blavatsky seems to be a link between the hen and A.L.P. who wrote ‛lettering you erronymously’ ... ―Atherton 236

In I.5 the Letter will be discovered by the hen Biddy Doran, who is also alluded to here: a bitty door.

The Serpent

Here is a list of the allusions in this paragraph to the serpent in the Garden of Eden:

an engels to the teeth who, nomened Nash of Girahash, would go anyoldwhere in the weeping world on his mottled belly (the rab, the kreeponskneed!) for milk, music or married missusse ...

German Engel : angel

Hebrew nakhash : snake

Genesis 3:14: Upon thy belly shalt thou go

creep on his knees

Serpents too are gluttons for woman’s milk, as Bloom tells his grandfather in Ulysses 485. The idea goes back at least to Isidore of Seville in the early 7th century, though this may not have been Joyce’s source:

The boa (boas), a snake in Italy of immense size, attacks herds of cattle and buffaloes, and attaches itself to the udders of the ones flowing with plenty of milk, and kills them by suckling on them, and from this takes the name ‘boa,’ from the destruction of cows (bos). ―Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 12:4:28 (Barney et al 257)

The Biblical phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth is usually associated with the punishment of the wicked at the Last Judgment rather than the Expulsion from the Garden. This passage, then, knits together the two ends of Creation: Genesis and Revelation.

Loose Ends

he reglimmed? presaw? HCE is unsure whether he is remembering the past or foreseeing the future. But history according to Vico is cyclical, so in a book like Finnegans Wake there is no difference between the two. To glim is slang for to see. In both Dutch and German glimmen means to glow, shine.

the fields of heat and yields of wheat where corngold Ysit? shamed and shone. The principal allusion is to Lord Byron’s epic satire Don Juan 3:86: The Isles of Greece, the Isles of Greece! Where burning Sappho loved and sung. These are the opening lines of a poem of sixteen stanzas that interrupts the 111 stanzas of Canto III. The poem laments the subjugation of the cradle of Western civilization to the Ottoman Turks. Joyce filters the lines through Vico’s The New Science, in which the point is repeatedly made that grain was the ancient world’s first gold:

The poets expressly relate that this was the first age of their world, when through the long course of centuries the years were counted by the grain harvests, which we find to have been the first gold of the world. This golden age of the Greeks has its Latin counterpart in the age of Saturn, who gets his name from sati, “sown” [fields]. ―Vico, The New Science §3 (Bergin & Fisch 4)

According to FWEET, Iseult’s hair was as fine and gold as cornsilk, though no source is cited for this. In Joseph Bédier’s Le Roman de Tristan et Iseut, Iseult is the fair Iseult with the golden hair (Simmonds 20 et passim), but her hair is never compared to cornsilk. Corngold is a surname from the German Korngold, but I don’t know if Joyce had any particular person in mind.

had not wishing oftbeen but good time echoing a line in the 1922 song Carolina in the Morning: Wishing is good time wasted, still it’s a habit they say.

within his patriarchal shamanah, broadsteyne ’bove citie (Twillby! Twillby!) HCE is also looking forward to the foundation of Dublin:

Anglo-Indian shamiana : pavilion, marquee

Broadstone: part of Phibsboro in Dublin, the site of Broadstone Railway Station, at the top of Constitution Hill.

Steyne (Steine): Dublin’s Long Stone, the ceremonial standing stone that the Vikings erected to mark the foundation of Dublin in the 9th century (or, perhaps, the refoundation of the city in the early 10th century). The original Long Stone is now lost, but a replica designed by Cliodhna Cussen was erected on College Green in 1986.

Danish by : town. The allusion to George du Maurier’s 1894 novel Trilby reminds us that the novel’s eponymous heroine Trilby O’Ferrall is half-Irish. Her relationship with Svengali is reminiscent of those of HCE with Issy, Lewis Carroll with Alice Pleasance Liddell, or Jonathan Swift with Stella & Vanessa.

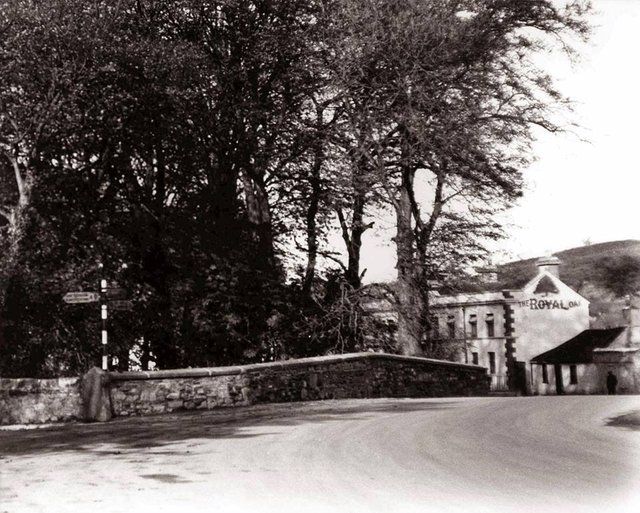

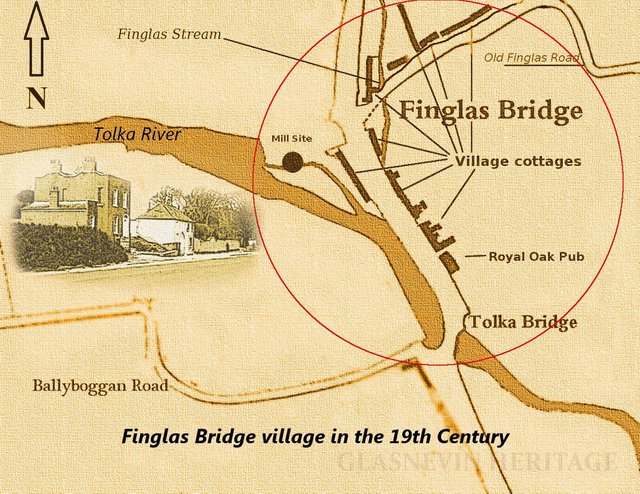

- a kingbilly whitehorsed in a Finglas mill King Billy is a common Irish nickname for William III, the Dutchman who triumphed at the Battle of the Boyne. Has he been conjured up by all the Dutch expressions in this paragraph, or did his presence conjure them? He is traditionally depicted riding a white horse. HCE, a Protestant, has a white horse―that skimmelk steed (RFW 206.28)―above his door to advertize his loyalty.

After his victory on the Boyne in 1690, William moved south and camped for four days in the vicinity of Finglas, a few miles north of Dublin. William himself stayed in the mansion house attached to a water-powered mill, which stood on the River Tolka between Finglas Bridge (which crossed the Finglas, a tributary of the Tolka) and Tolka Bridge (which crossed the Tolka). On 17 July William issued from there the Declaration of Finglas, offering a pardon to Jacobite forces who agreed to surrender. Both the mill and the house were destroyed in a fire in 1827. Neither bridge survived the development that overtook this picturesque area in the second half of the 20th century.

ex profundis malorum Latin out of the depths of evils. The allusion to Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis reminds us of another Irishman who was hounded and incarcerated.

sigarius (sic!) vindicat urbes terrorum The original Latin reads Securus iudicat orbis terrarum : The judgment of the World is secure or the verdict of the World is conclusive. It was written by Saint Augustine but made famous by Cardinal Newman, who claimed it greatly influenced him in his conversion to Catholicism. What Joyce actually wrote is : Sicarius vindicat urbes terrorum : the assassin sets free the cities of terror. The assassin is HCE’s attacker.

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Stephen A Barney (translator) et al, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2006)

- Goddard Bergin (translator), Max Harold Fisch (translator), The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Third Edition (1744), Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York (1948)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 4, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, Translated into English by Luigi Ricci, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1921)

- Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, Third Edition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (2006)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Florence Simmonds (translator), The Romance of Tristram and Iseult, Translated from the French of Joseph Bédier, William Heinemann, London (1910)

- William York Tindall, A Reader’s Guide to Finnegans Wake, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York (1969)

- Peter Washington, Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon: A History of the Mystics, Mediums, and Misfits Who Brought Spiritualism to America, Schocken Books, New York (1995)

- William Butler Yeats, Autobiographies: Reveries over Childhood and Youth and the Trembling of the Veil, The Macmillan Company, New York (1927)

Image Credits

- The Prisoner of Gisors: Edward Henry Wehnert (artist), Frederick Bacon (engraver), Art Union of London (1848), Public Domain

- Oscar Wilde in Rome in 1897: Anonymous Photograph, William Andrews Clark Library, Public Domain

- Eden in Armenia: A Map of the Terrestrial Paradise, Emanuel Bowen (engraver), (1780)

- The Sacred Blue Lily of the Nile: © Peter Bubenik (photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Phoenix Park Tea Rooms: © arno^ (photographer), Fair Use

- The Sihlpost Building, Zürich: © Bobo11 (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in 1889: Anonymous Photo, Public Domain

- The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man: Peter Paul Rubens & Jan Brueghel the Elder (artists), Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands, Public Domain

- Finglas Bridge: Patrick Kirwan (circa 1960), Public Domain

- William III at the Battle of the Boyne: Jan Wyck (artist), Government Art Collection, Old Admiralty Building, Admiralty Place, London, Public Domain

- Finglas Mill Map: Anonymous Map, Fair Use

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Finnegans Wake Notes

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog