The hunt is on

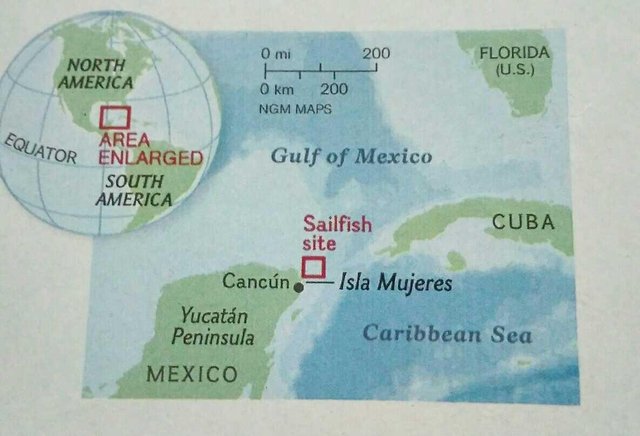

Fifty miles northeast of Isla Mujeres in the Gulf of Mexico, sailfish prowl through blue waters. Frigatebirds hang like arrows above the sea, dipping down now and then to grab a meal. Fol- lowing their lead, Anthony Mendillo, sporttish- ing guide and expert sailfish chaser, steers the Keen M toward the flocks. Sure enough, below the birds a school of sardines hundreds strong moves as one, flashing in the sun with each turn. Dozens of long shadows orbit the ball of frantic fish: the hunters.

Sailfish and sardines are migratory and widely distributed, with populations in multiple oceans. But from January into June, Istiophorus platypter- us and Sardinella aurita meet fish to fish in this stretch of sea. For predator and prey the conti- nental shelf here makes ideal habitat. Plankton- rich shallows, nourished by rivers draining the mainland and ocean currents pushing between Cuba and the Yucatan, promise ample food.

The hunt seems almost mammalian. Sailftsh- which often travel iii loose groups-clearly join forces. Males and females alike circle the prey, pushing the school into tighter formation, and taking a few bites iii turn. Each forward rush is punctuated by a startling flare of the dorsal tin, which more than doubles the hunter's profile.

(Map target Sailfish)

An iridescent flash along the body, often in silvery blue stripes, adds to the effect. Darkly pigmented cells called melanophores are "like venetian blinds," says neurobiologist Kerstin Fritsches of the University of Queensland, in Australia. Ordinarily the animal appears dull, but "during stress or excitement, the cells con- tract their pigment to expose gorgeous metallic colors in the skin below."

Color bursts may serve not only to unsettle prey but also to warn other sailfish to stay back, helping avoid collisions. 'Given their po'nty noses and swimming speed, this would be important" Fritsches says. Indeed, sailfish bills- elongated upper jaws that the hunters whip left and right to batter prey, and likely wield against sharks, marlins, and other enemies-are dagger sharp. Yet despite their rapid-fire strikes, reports of sailfish skewering one another are hard to find. The fish take turns-and it appears no one loses an eye or goes hungry in the renzy.

The sardines, too, work in concert. Detecting each other's proximity and movement, they shift in synchrony, each fish both leader and follower. The fish mass slides like a drop of mercury, mes- merizing, with a shimmer that may help to con- use predator.

But no hypnotic dance can fully protect the sardines, which will hide in a squirming mass under any bit of flotsam-even a snorkeler. The sailfish simply wait within striking distance for their prey to be exposed. Soon the hunt is back on, predators again corralling, swatting, swallowing. After a rush to mop up the leftovers, the deadly game is over, and the sailfish retreat. In their wake, drifts of glinting sardine scales fall slowly into the blue.

Like wolves on a caribou herd, sailfish cooperate- sometimes for several hours--to turn unwieldy pre! into a manageable meal. The predators shoot in from aii sides, popping open fins and flashing iridescent coiors as they get up close. "It's like saying, Boo! i'm here!,, says marine scientist Guy Harvey, a longtime sailfish observer. "There's a shock effect that pushes prey together." Once a ball is under control, the sailfish take turns shooting through it, heads whipping side to side as they use their bills to bat sardines (center) with remarkable precision.

Pursuers then nab stunned fish before they can escape. Whittled down to its last bloody stragglers, the ball spins in a slow vortex (bottom), prey exhausted and no longer in perfect concert. Typically sailfish will consume every last one.

Hello, as a member of @steemdunk you have received a free courtesy boost! Steemdunk is an automated curation platform that is easy to use and built for the community. Join us at https://steemdunk.xyz

Upvote this comment to support the bot and increase your future rewards!