Love in cyberpunk

William Gibson's Neuromancer is a romantic novel in more than one sense. It is, to begin with, by virtue of the skillful oxymoron that serves as its title: "neuronal romancero" or "new romancero", something like "love in the times of brain prostheses".

But if it were enough to usurp the theme of love, then the tearful farce of the Titanic and the pitiful screams of Julio Iglesias would qualify as romantics. Beyond the erotic theme, the reason that interests us is that Neuromancer retakes what was the leitmotif of nineteenth-century romanticism: "I'm not a machine"

Indeed, like the poems of Wordsworth, the horror stories of Poe and the Frankenstein of Mary Shelley, Gibson is inscribed in the genuine romantic tradition, the one that discovers and explores our humanity beyond the instrumental reason, in the great passions: hatred, fear, love, freedom ...

How does Gibson fit into a dead tradition more than a hundred years ago, a tradition that today only survives in the media betraying itself as a machine to produce emotional effects? Answer: avoiding what was the ruin of late romanticism, namely, the excessive worship of the heroic past and the nostalgia of nature.

By dint of condemning the prosaic character of the present and of vindicating emotionality, nineteenth-century romanticism ended up taking refuge in tradition and consoling itself in a hypertrophic melancholic sensibility. It was thus that the metaphor of the machine world was replaced by the agrarian metaphor of culture. "I'm not a machine." "What are you so?" "I am a plant," our late romantics seem to respond. In this way, romanticism could only end in what ended, in mere exaltation. Dangerous exaltation in the era of nationalism; innocuous exaltation in the opposition between the real world and the world of culture; fainthearted exaltation in our current improvement manuals, those that speak of the extranumeric values of the "human resources", those that maintain that in addition to being numbers, we have culture, feelings and a thousand etceteras.

In more than one sense then, Gibson is not a romantic, not at least to the extent that his frenetic prose is totally alien to the nostalgia of tradition. Unlike Wordsworth who seeks Proteus in nature or in the past, Gibson clings to the monster with only one thing in mind: the imagination of the future.

It is pertinent at this point to remember Proteus, the multiform marine god and fortune-teller who answered the questions of the one who managed to cling to him throughout his transformations. Among the difficulties that the tenacious questioner had to overcome was the unbearable stench of the god. Seal shepherd, Proteus was impregnated with the foul stench of newborn seals.

As tenacious as the Menelaus of the Odyssey, Gibson does not let himself be intimidated by the multifaceted and seemingly unattainable nature of the "cybernetic" world or by the stench of his neonates.

The reward is immediate: beyond the nostalgic laments of the apocalyptic of the computation, beyond the narcotized automatism of its integrated, in short, beyond any cybernetic fatalism, Gibson is capable of wishing the future world, is capable of imagine him squalid, promiscuous, barbaric, but above all, amazing.

Like the nineteenth-century romantics, Gibson is determined to rediscover the mystery that is the world and man beyond the calculating reason that today disperses and impoverishes him; unlike those, he does not want to carry out that project by turning his back on the world, but crossing it.

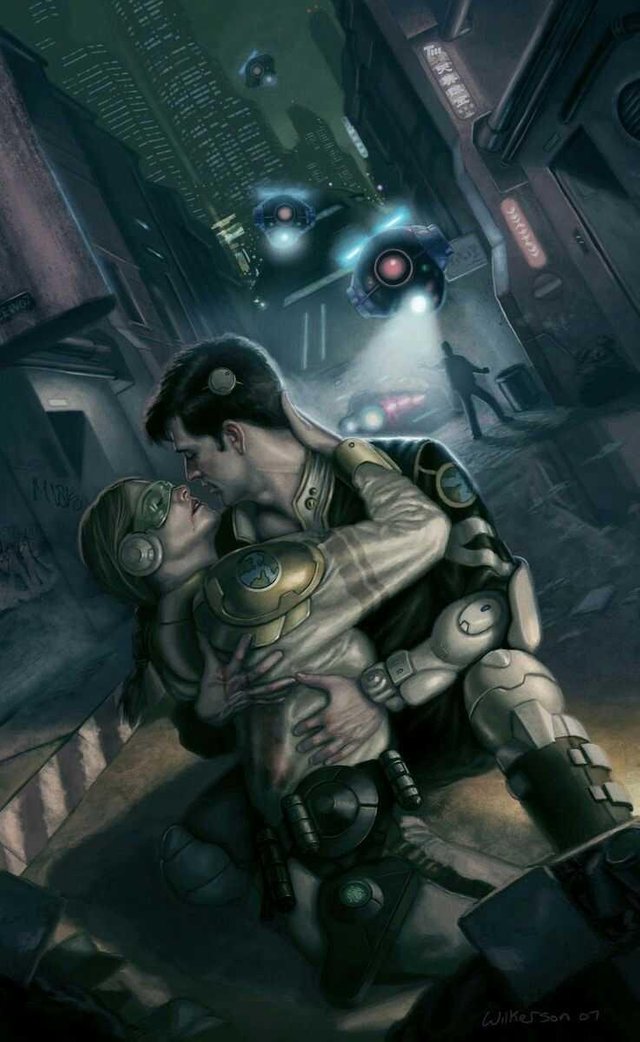

What does the reader find crossing the brave new world Gibsonian? A hero who is not a machine despite his efforts to behave as such; a heroine full of electronic implants who suspects that weakness in the hero; a dead cybernaut endowed with digital immortality; an immense artificial intelligence perplexed by what is not a machine; a rotten and overpopulated planet; a labyrinthine and dazzling space station; a murder in "cyberspace"; a "cyberspace" more.