Commerce in the viceroyalty

The precious metals extracted from the American colonies became the basis of trade for the expansionism of Spain and the consolidation of European economies, in addition to stimulating their foreign trade and allowing them to subsidize the numerous wars that led the absolutist monarchies at the beginning of the modern age. For this reason, in the sixteenth century an exclusive commercial policy and a series of instances of state control were established that would allow the greater amount of these metals to be exported to the peninsula in the most efficient manner.

The exclusivity of commerce

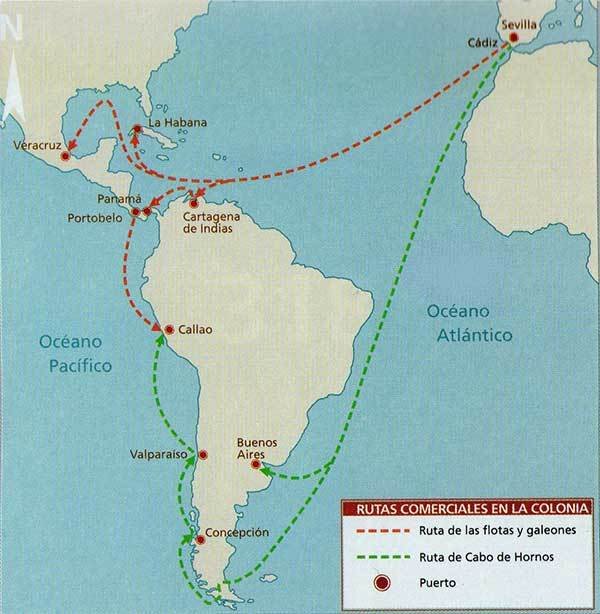

With the aim of preventing the precious commercial cargo from being affected by contraband or pirate attacks, among other fiscal and military reasons, the Atlantic exchange had to take place exclusively between Seville and the American ports of Havana, Veracruz, Cartagena, Portobelo, Panama and Callao. In addition, all commercial vessels had to travel together, in the so-called system of fleets and galleons.

This system benefited the Andalusian commercial monopoly, since Seville had to supply the colonies with a long list of products -from iron to olives- that, in theory, Peru should not produce. In this way, the colonies would be ideal markets for Spanish products and European goods marketed by Spain.

Commercial Routes in the colony

It was known as La Carrera de Indias to the activity of the galleons that had to transport precious metals from the colonies to Spain and, back, to bring the Indian products from the Peninsula.

In the race, two annual fleets intervened, escorted by warships, and directed to the two American viceroyalties.

The Fleet of New Spain carried goods to Mexico, while the galleons of Tierra Firme had as their destination the viceroyalty of Peru.

The Spanish crown controlled all maritime and commercial traffic with the Indian through two institutions: the Indian Council and the contracting house. The latter was in charge of granting licenses and registering ships, controlling and supervising cargoes and it came to function as a court of justice in matters of a commercial nature.

The Peruvian Competition

The Andalusian monopoly could not supply the great demand for goods from the American colonies. In the case of the Peruvian viceroyalty, the intense development of the internal economy thanks to mining exploitation had encouraged the flourishing of a series of commercial activities, such as textiles and agriculture, which already supplied not only nearby markets - mining settlements and cities- but they started exporting goods to other colonial territories.

Lima, thanks to the port of Callao, articulated an extensive maritime merchant network, with circuits from Acapulco to Valparaíso, and which was also linked to the productive centers within the Peruvian territory. The intercolonial exchange of products was so intense that it became an obstacle to the Spanish monopoly system. The case of Peruvian wines is emblematic to understand the discomfort of the Crown.

During the sixteenth century, the valleys of Arequipa and Ica turned to the production of wines and spirits, products that were not only consumed in the viceroyalty, but were in great demand in Central America. In the first decades of the seventeenth century the Peruvian wine had displaced the Spanish, which motivated the Crown to prohibit, under severe penalties, its commercialization in Panama, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

However, European products continued to be in demand in Peru, as many of the Peruvian products did not reach the quality of the imported products.

Peru, Mexico and the Manila Galleon

The exchange of Peruvian silver for Mexican manufactures motivated an early commercial activity between the viceroyalty of Peru and that of New Spain.

From 1570, genres from the Far East began to join this commercial exchange. The Asian products arrived in the Philippines and from there they were transferred to Acapulco in the so-called Manila Galleon. The usual shortage of American markets caused by sevillanas monopolistic practices made very attractive products such as silk, perfumes and jewelry made in China, Indonesia and Japan, which were usually much cheaper than their European counterparts. So Mexico became a warehouse for the re-export of Asian products to Peru.

The contracting house and the Consulate of Seville, in charge of controlling the marine trade with the colonies, pointed out in the seventeenth century that the traffic with the Philippines had been one of the main causes of the deterioration of the Atlantic trade.

In order to safeguard the interests of Seville, that traffic was restricted, and in 1631 all commercial activity between Peru and Mexico was prohibited, to prevent the flight of Peruvian silver to the East. However, trade between Peru and the Philippines continued to be very active, albeit clandestinely.

Direct Trade

The successful American trade attracted the interest of the European powers that, aggressive or friendly, appeared on the same circuit of the Spanish fleets. French, Italian, Flemish and English merchants knew how to take advantage of Spain's inability to satisfy American demand for products. Towards 1680, and having as its center the port of Cádiz, non-peninsular mercantile agents accounted for eighty percent of commercial traffic. The merchants of Peru, called peruleros, also knew how to take advantage of the situation. They dodged the Portobelo fairs for their high prices, mocked Sevillian commercial circuits and taxation, and they embarked directly to Spain to buy from foreign suppliers.

Meanwhile, France, Holland and England established points of support in the Caribbean for trade with the American colonies and, by the end of the seventeenth century, direct mercantile circuits had already been established with the Spanish colonies. In the mid-seventeenth century the inspection of the fleets collapsed, whose excessive fiscal burdens opened the doors to smuggling. In the chaotic context of the Spanish War of Succession, the regime of fleets and galleons was officially abolished in 1739.

Credit and Commerce

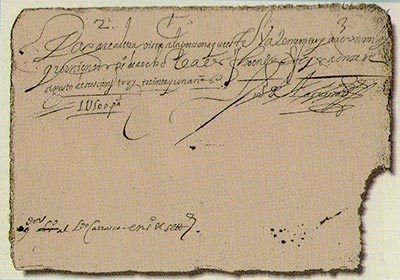

It was possible to access credit through the church and the merchants. In the case of the ecclesiastical institutions, the feminine orders had an important paper, because they disbursed great sums in favor of the State and the landed elite. On the other hand, credit networks related to trade were established, with professional lenders who used sophisticated credit instruments in their transactions.

The public Banks

The banking operations carried out by some merchants of Lima forced the council to legislate the operation of what was called public banks since the end of the 16th century. From then until 1604, seven banks existed in Lima, a unique case in Spanish America.

Public banks received deposits and carried out credit operations theoretically supervised by the authorities.

But as there was no real control over the bankers' investments, the banks went bankrupt.

In the photo, a voucher from the Bank of Juan de la cueva (1615).

The Pirates and the Callao

The Callao was until well into colonial times the most important port of Spanish America. That's why it should not be surprising that he was, at that time, the victim of attacks by pirates, corsairs and filibusters.

In 1579, the legendary English privateer Francis Drake reached its docks, but did not dare to disembark for fear of the power of the royal army of Viceroy Toledo. Eight years later, in 1587, the English corsair Thomas Cavendish is about to invade the callao, but the Spanish forces come to meet him and fiercely repel the invasion. Years later, in 1594, the English pirate Richard Hawkins, commanding his ship Linda, faced the Spanish army and was defeated.

In 1615, the terrible George Spilbergen, commanding a Dutch fleet, ravaged the harbor causing damage and great anxiety. In 1624, the Dutch corsair Jacobo Clerck, better known as L'Hermite, occupied San Lorenzo Island for three months, from where he made repeated incursions both to the callao and to other ports of the Peruvian coast. Such was the effect of the prolonged siege that the colonial authorities decided shortly after to build great defensive walls against this type of attacks. The last English pirate who tried to reach Callao was Thomas Davis, who is known to have been the French filibuster Roggier Wodes, who caused no major damage.

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by CryptoLeader from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.

Congratulations @aldahyr77! You have completed the following achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!