ADSactly Education: Dealing with Accents in Language Teaching and Learning.

Almost two years ago, I wrote a commentary on Julia Alvarez’s novel How the Garcia Girls Lost their Accents:

Here is the Spanish version of the same article

This novel, like many other texts in the so-called Post-Colonial Literature, depicts the drama of the person who tries to merge and be accepted by the host country, even if that means losing their identity (or at least trying to).

The accent, that unwanted marker of foreignness, or the hiding of it, becomes one of the main obsessions of the foreigner who feels compelled to exercise some sort of “linguistic passing” in order to succeed in the new country. But, can we learn a second language without an accent? If not, can we eventually lose our accent? Should we? What are the pedagogical implications of such a controversial issue?

The Phonetic Machine Behind All Languages

Every learner has to know that all languages are made of sounds (phonemes) that combine to form words, which align in phrases and sentences to form speech. This speech depending on the area (even within the same linguistic geography) will carry a certain cadence or rhythm which in combination with the different intonations used by speakers in different speech acts constitute the linguistic baggage we call language.

Thus, theoretically, the closer our phonetic map is to the language we are learning, the closer we are to speaking “without an accent”. However, even among speakers of the same language there are accents that identify their regional differences. These differences are usually subtle and do not compromise mutual intelligibility, but occasionally regional accents can hinder communication.

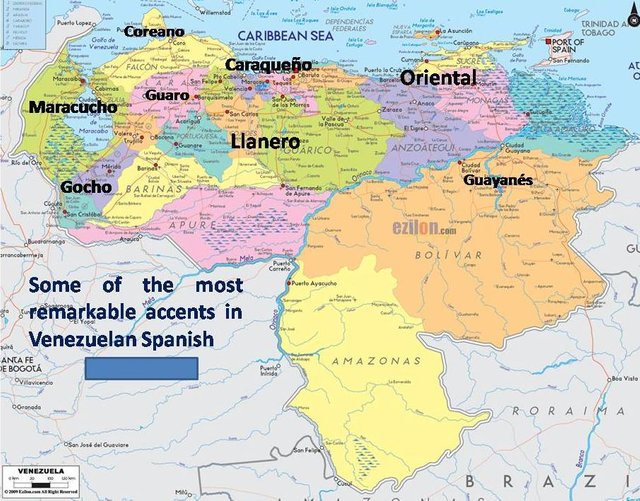

Here’s an example of how Venezuela can be divided depending on the regional accents of their people.

When we add to the accent some semantic units that are used differently from one region to another, or worse yet, words that are used only in a specific region, then mutual intelligibility among the speakers of the same language can be compromised. Most Venezuelans from the central part of the country will say that they can’t understand orientales or maracuchos (they speak too fast and have some funny swing no one else has). The fact is that every region makes fun of the rest of the countries’ accents.

Now, when it comes to learning another language there will be more general features and accentuated differences that will broadly reveal the speaker’s origin or nationality.

Take Chinese, for example. The Chinese people who learn Spanish as adults, not having the /r/ sound in their phonetic repertoire, will almost unavoidably substitute every /r/ sound for an /l/ sound; add to that the tonality that characterizes the Chinese language, and we’ll get utterances such as /el pelo come alo/, when they meant /εl 'pε.ro 'ko.me a.ros/ (the dog eats rice= el perro come arroz). This kind of extrapolation allows people to imitate, usually derisively, the accent of foreigners. We simply catch the changes/alterations/errors they make when they speak our language. The same procedure can be used for learners to know the emphasis they’d have to make to sound as a native speaker.

Spanish-English Comparison

The first thing we have to know is that speaking another language is a performance (at least in the first stages of the learning process; it eventually comes naturally). As such, just like the actor who learns lines by heart and has to act them later (adding what we might call the suprasegmental or prosodic aspect to the words), the language learner has to do some acting, some imitation, if you will. Pronouncing isolated words correctly will not be enough if in context they are not given the right rhythm and intonation. I remember one teacher in particular when I started to learn English in college, back in 1991, who we thought was a different person when she spoke English as compared to who she looked/sounded like when she spoke Spanish. That was part of the performative aspect I am talking about.

It follows, then, that some psychological inhibitions may hinder the learning of the second language or at least the acquisition of a native-like pronunciation. This does not mean that outgoing people would learn better than shy people, for instance, since a number of other factors, such as age, exposure, physiology, and environment can intervene.

When we compare Spanish (a phonetic language) with English (a language that is written one way and pronounced another), we will see that phonetically neither language is easier or more difficult than the other. The possibilities of an English speaker speaking Spanish with an English accent are as high as those of a Spanish speaker speaking English with a Spanish accent. It all goes back to the shared phonemes and the previously mentioned factors. Age, for instance, is a determining factor: the younger the learner the highest the possibility of speaking the target language without an accent. That being said, there are many case of older learners that manage to achieve an accent-free second langue thanks to more exposure, discipline, especial training/speech therapy, personal resolve, etc.

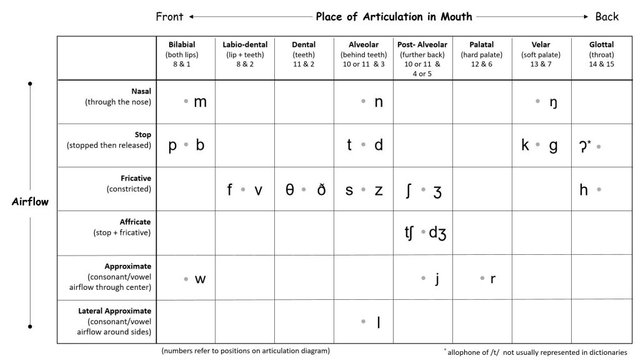

Sounds in English

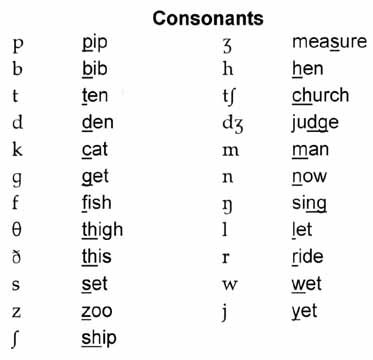

In this chart we can see the English consonants and their corresponding phonetic symbols.

Here are some examples of how those symbols correspond to some of the occurrences.

What complicates things for Spanish speakers is that, for example, the letter “d” in den will not always sound /d/. If we read in a word like education in will sound like the /dз/ sound of judge. But, Spanish speakers will almost invariably pronounce the /d/ sound.

Then, we have the issue of position. Even if we share the same phoneme, chances are that depending on the position in the word, it may be difficult to replicate. Take /s/, for instance. There are not /s/ sound in Spanish at the beginning of a word followed by a consonant sound. We have words like sí (yes), soñar (to dream), but we don’t have words like school, speak or study, so we will most likely say /eskul/, /espik/, /estodi/. The adding of an /e/ sound before the /s/ is a peculiar feature of Spanish speakers.

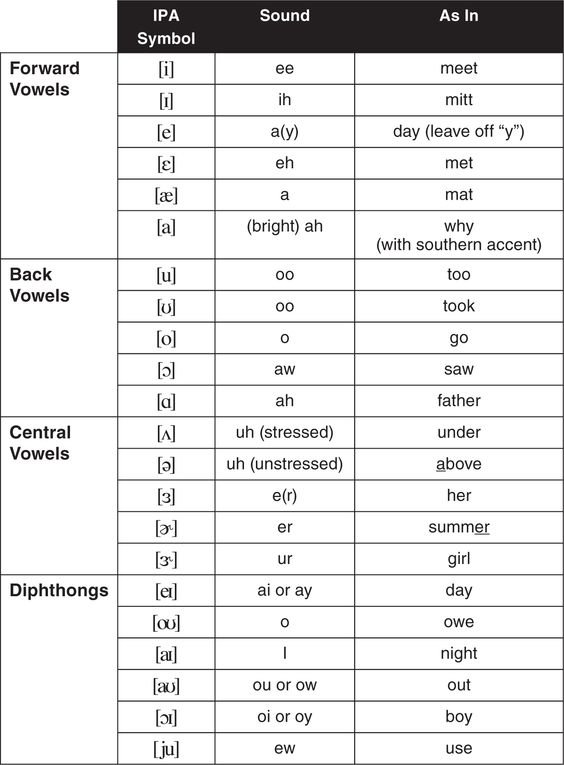

With the vowels it gets even more complicated. There are at least some 12 vowel sounds in English (it can be more or less depending on the region), while in Spanish there are only 5 distinctive vowel sounds.

English Vowels

Spanish Vowels

As you can imagine, Spanish speakers will not perceive the difference between, say, beach and bitch, since we have only one /i/ sound; and the same goes for every other vowel in the alphabet: fool vs. full, cull vs. cool, or bot vs. but.

Thus, for instructional purposes, it is important that students and teachers understand the particular phonetic differences of the first (native) and second (target) language. That way measures can be taken on both sides to emphasize those aspects or elements that will predictably require additional work to achieve near-native performance.

Are Accents a Negative Thing?

Accents are part of our identity, but they can tell very little about where we come from, what our background is, or where we stand on a given issue. Although for many people accents can be intriguing, fascinating, musical, and even sexy, the fact is that in these conflicting times we are living, accents are read as origin, nationality, race, or religion with all the negative connotations all those denominations can bring.

For professional purposes, for instance, to have an accent may be the difference between getting a job or not getting it. For teachers, this can be particularly conflicting considering that teachers may be highly qualified, and yet considered unfit for the job because native students may complain about their accents. I saw a lot of this in American universities.

Most people probably embrace their accent with pride. Depending on where they are and what they do they may not have to hide their origin. But, for many having an accent may be a negative mark they’d rather erase or hide, lest they be seen as inadequate, inferior, or unwelcome.

Are Some Accent Better than Others?

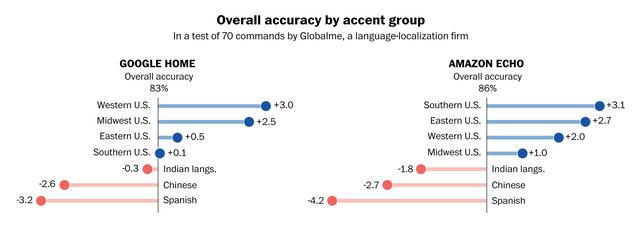

From a linguistic and pedagogical perspective, obviously no. as long as people can communicate in the target language, the accent means little. However, politically speaking, we know that the answer can be more complicated. Depending on our place of origin we may enjoy certain perks or suffer certain consequences. Technology may contribute to make things worse once more in this regard. I ran into this interesting report regarding a popular voice recognition device:

Dylan Zwick, from Pulse Labs sees the economic aspect of the problem

However, while strides are being made on all fronts, some accents may be at a disadvantage relative to others, and this may hurt voice device adoption within some demographics.

no matter how good the voice platforms get at correctly converting speech into text, there will always be times when what a user said either isn’t understood, or is misunderstood.

We can anticipate more serious socio-political problems emerging from these results if we give technology too much credit. Maybe the world should learn a lesson or two from linguists and language teachers.

written by @hlezama

Click the coin below to join our Discord Server

)

Why has this been so heavily downvoted? smooth gave a 100% downvote?! What is that?

This post is very well composed, researched, analyzed, cited and thought provoking. The works.

Thanks, @owasco. I had been mortified since it came out trying to figure out why. I hope it has nothing to do with the content. I always to my best to be as balanced as possible and as professional as possible when it comes to academic work.

I can see why you feel mortified, it's a great post. Hopefully the downvote was in error and will be corrected.

We're not exactly sure why either, we have tried reaching out to @smooth regarding the downvote.

Posted by @morkrock

Very good work of excellent academic level, but also with contextual reflection. I understand that for certain work tasks or functions (such as teaching a language), having an "accent" (national, regional, local) may imply some disadvantage, as long as it cannot be controlled. Nevertheless, I believe that it is inevitable and necessary that "accents" be assimilated. Perhaps we will arrive at a language where everything is mixed or where the separations are more and more closed; it is almost a question of novel or cinema of anticipation.

Thanks for your post, @hlezama.

Thanks, @josemalavem

There is this movie I watched a movie some years ago, Code 46, starring Tim Robbins, where people speak a language that is a collage of some of the main languages in the world. I think that multicultural exposure can take us there, even though multiculturalism has been demonized for political purposes.

A great post. What can I say? It is well documented, easy to understand, with an academic language necessary to develop this theme. I congratulate you @hlezama even for the initial cartoon. I keep reading you

Thank you very much, @marcybetancourt. Glad you enjoyed it. Always a pleasure to interact with you.

I think that is justified if and only if one's accent is as heavy as to result in pronunciation errors severe enough to hamper understanding. Otherwise the students should just learn to suck it up. The natives can also have annoying accents. It's ultimately a matter of perspective.

Most people probably embrace their accent with pride. Depending on where they are and what they do they may not have to hide their origin. But, for many having an accent may be a negative mark they’d rather erase or hide, lest they be seen as inadequate, inferior, or unwelcome.That is true and groups of native speakers are not free from that. In my personal view, an accent is fine as long as one follows the general pronunciation rules of the language. There are such rules that no dialect of English deviates from.

Right. You made some good points. Regarding rules, the phonetic palette of each language can be flexible enough to allow regional or even national variations of the same phoneme.

Take /ei/ for instance, produced in closters such as face or mate. The general rule may be to pronounce "a" as /ei/ when it precedes a consonant and a silent "e", and yet in some regions face is pronounced /fais/ and mate /mait/. However, those may be uncommon variations and learners should always aim at the "mainstream" variations.

Students in Latin America usually debate whether they should learn the British or the American pronunciation (usually implying that one is better than the other). One may be more "used" (as measured by number of speakers) than the other, but learners do not ned to get into the geopolitics of language. To be on the safe side, as long as they coherently adopt either accent (or at least the most distinctive features), they'll be fine (it would be otherwise weird to pronounce certain words a la americana and other a la britanica).

Fortunately, British and American Englishes are not too far from one another in terms of vocabulary or pronunciation. There is no risk of serious misunderstandings. It might be better to pick American if your goal is to become proficient at English. That's because some parts of colloquial British vocabulary tend to be not well-known to most people who speak English as a second language or even North Americans whereas the British usually have enough exposure to American English to know the American counterparts of those words.

Exactly. And even within the different registers of American English, there are regional variations that can challenge any other speaker's understanding, even native speakers of english, let alone L2 learners. But the beauty of linguistic interaction is that exposure and openmindedness can easily help overcome these communication hurdles.

Hola adsactly,

Tu post ha sido seleccionado por el bot de @provenezuela, te hemos dado un voto en apoyo a los autores venezolanos!

Gracias por ser parte de nuestra comunidad!

Gracias por el apoyo, @provenezuela

Great academic view on the world accents, even if myself I quite enjoy the specific of each zone and that simply shows that diversity is better than anything out there or anyone that would try to make us fell or behave the same.

Thanks for taking part of the conversation. I think this is a fascinating topic and here on Steemit we have people from so many parts of the world who speak English with different accents and even grammar variations. We can learn a lot from this exposure

Excellent work, of great value and depth, @hlezama. I am one of those people who can recognize the origin of other people by their accent when speaking. These days I was watching a television program where some Venezuelan actors complained about how they had to assimilate the Mexican accent to be able to make soap operas in that country and that when they arrived in Miami they had to leave it, because in Miami they prefer more the Venezuelan accent that is more neutral and international. There are marks and traits that make us common to others. The accent is one of those features. I congratulate you for this work, my friend!

Thank you very much, my dear. Your comment adds a wonderful example of what I suggested in the post about the negative impact an accent can have in the job market.

Nice piece 👌, great article!

Posted using Partiko Android

Thanks

Hi, @adsactly!

You just got a 0.3% upvote from SteemPlus!

To get higher upvotes, earn more SteemPlus Points (SPP). On your Steemit wallet, check your SPP balance and click on "How to earn SPP?" to find out all the ways to earn.

If you're not using SteemPlus yet, please check our last posts in here to see the many ways in which SteemPlus can improve your Steem experience on Steemit and Busy.