How Mushrooms Could Repair Our Crumbling Infrastructure

The U.S. has one of the most advanced economies in the world. And yet the concrete infrastructure that supports it—the roads, bridges, sidewalks, and so on—is slowly crumbling. This deterioration requires complex repairs, causes long delays, and in the most severe cases can lead to structural failure.

Recommended for You

It’s Getting Harder to Spy on Employees (in Europe, at Least)

New Google Street View Cameras Will Fuel AI Assistants

FDA Approves Groundbreaking Gene Therapy for Cancer

This Robotic Vacuum’s Maps of Your House Are the Coolest Thing Since the Roomba

Human Embryo Editing Study Shows We Still Have a Lot to Learn About CRISPR

It’s also an increasingly expensive problem. Small cracks left unrepaired develop into bigger ones that expose metal reinforcement structures, and when these are damaged, repairs can be costly and complex. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, this problem will cost the U.S. economy almost $4 trillion in lost business by 2025 if it’s not addressed.

Clearly, a better, cheaper way to repair concrete is desperately needed.

Enter Ning Zhang at Rutgers University in New Jersey and few pals, who say they have discovered a secret ingredient that could one day keep the nation moving by repairing crumbling concrete automatically. This new ingredient? Mushrooms.

First some background. Materials scientists have long hoped to find a secret sauce that helps concrete repair itself. One idea is to fill concrete with polymer fibers containing resin that leaks out to fills cracks.

That looked promising for a while, but it turns out that concrete and resin have different thermal expansion properties, among others, which can sometimes make cracks worse.

A better filler for cracks is calcium carbonate, because it bonds well with concrete and has similar structural properties. Various bacteria produce minerals of this kind but also release other by-products, including copious amounts of nitrogen products like ammonia. And this can damage roads and the environment.

So materials scientists need another option, and today Zhang and co say they’ve found it in the form of a fungus called Trichoderma reesei. It can germinate in a wide range of conditions, forming a fibrous fungus that promotes the formation of calcium carbonate.

Their idea is that fungal spores are added to the concrete when it is mixed and then lie dormant until the concrete cracks. Water flowing into the cracks causes the spores to germinate, filling the cracks with fungal fibers that trigger the formation of calcium carbonate—which eventually fills the void.

That’s the theory, but the crucial question is whether it would work in practice. So Zhang and co set out to find out.

The team poured concrete into petri dishes and allowed it to set. They then poured a growth medium onto each slab and added various kinds of fungi. They waited to see which of the fungi would grow in the highly alkaline conditions that concrete promotes.

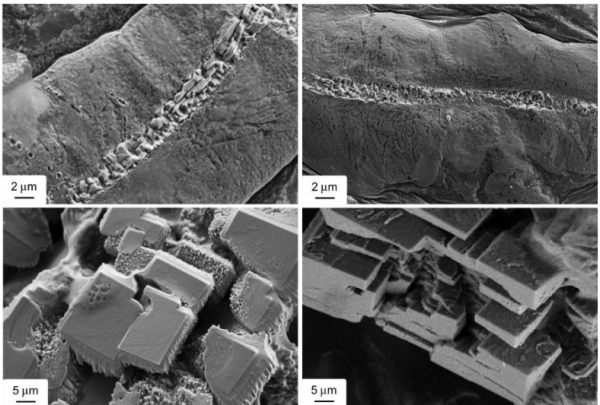

The results were revealing. Of all the fungi tested, only Trichoderma reesei flourished even when the pH rose to 13. Zhang and co then studied its fibrous structure under a microscope and used x-ray diffraction to analyze the deposits it left behind. “The data strongly suggested that T. reesei hyphae can promote calcium carbonate precipitation,” they say.

Electron microscope images clearly show the mineralized structures the fibers leave behind.

Of course, none of that proves that Trichoderma reesei spores can survive if added to concrete when it is mixed. Indeed, at first sight, that seems unlikely. The spores would have to sit in pores within the concrete.

Zhang and co measured the pores in the concrete they made and found that they were about one micrometer in diameter on average. But Trichoderma reesei spores are bigger—about four micrometers in diameter. That suggests they would be crushed as the concrete sets.

Zhang and co say the problem could be solved by adding air bubbles to the mix, but this needs to be investigated further.

That’s interesting work with a significant upside. If Trichoderma reesei turn out to be the magic mushroom that can repair the U.S.’s crumbling infrastructure, it will be a major boon. And it’s environmentally friendly, too—the fungus is benign as far as humans are concerned, and the process of forming calcium carbonate fixes carbon from the atmosphere. So it removes carbon dioxide, an important greenhouse gas.

Of course, there is much work ahead to determine whether the spores will survive in concrete. But the early results provide reason to study this in more detail.

you can't just copy stuff and repost it, especially without citing the source of your information, be careful