More Government Won't Fix Income Inequality

The Assertion

The subject of income inequality has been in and out of the spotlight over the past several decades. It is again in public discussions in recent years, as many in lower income groups find they can purchase less than before with the same number of dollars. One reason for this is inflation, caused by governments printing endless amounts of money to spend on various programs ranging from welfare to warfare. One view on income inequality is that it is wrong for such a situation to exist, and government policy should be used to correct it. Given that government is a primary cause of this situation, more government intervention is not the solution, in whole or part, to what many see as the problem of income inequality.

Positions which assert income inequality is an area of concern often view the issue as a moral or ethical one; data is presented, often in great and accurate detail, and is examined within a moral framework. In some of these presentations the assertion is made that inequalities in income are primary or contributing factors to real-world problems such as stress or lack of proper education. However, these presentations fail to objectively show a causal relationship between inequalities in income and various problems, often suggesting government actions to decrease the differences in income levels as well as address other problems.

An example of this view, entitled “Rising Income Inequality and the Role of Shifting Market-Income Distribution, Tax Burdens, and Tax Rates”, was written by Andrew Fieldhouse, who holds a M.S. in Economics from, and is an Economics Ph.D. Candidate at, Cornell University. Fieldhouse's report was written for the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a think-tank created to examine low- and middle-income groups and propose policies intended to improve the conditions of these groups. EPI's board of directors has included such individuals as economist Robert Reich, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, and USW President Leo Gerard.

According to Fieldhouse, government policymakers should be concerned with slowing the growth of income inequality, and one measure to accomplish this should be a tax system which pushes back against market-based income-inequality. While Fieldhouse's analysis of relevant data appears to be accurate and thorough, it fails to make an argument as to why income inequality is something which should be addressed via government policy. It also fails to, as 19th Century French economist and legislator Frederic Bastiat presented in his parable of the broken window, “see that which is not seen”.

The Unseen

In his parable, Bastiat explains it is easy to see the near-term or visible effects of an action or policy, but difficult for some to see the long-term or invisible effects. Some could argue that a child who breaks a window is really doing good for the economy and society, because repairing the window causes money to be spent and work to be done. This is known as “the seen”. However, what might the window owner have done with their money had they not needed to replace a broken window? Perhaps they would have purchased something, invested the money, or loaned it to another (via a credit union).

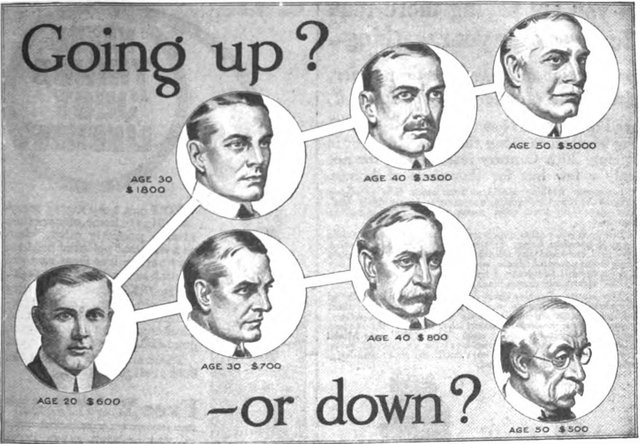

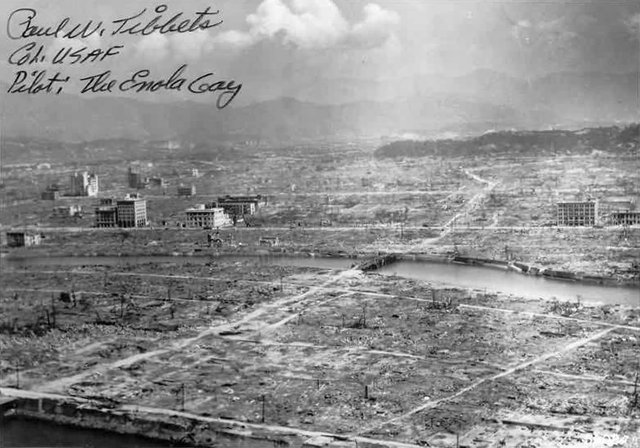

If a broken window is good for the economy, a bombed city should provide an astronomical boost to the economy...but at what cost

If a broken window is good for the economy, a bombed city should provide an astronomical boost to the economy...but at what costWhen a window is broken, the window owner and society have less than they did before the window was broken. The total amount of money in existence does not change, but the window as well as the labor and resources which went into making it are gone. However, when a window is not broken, society has a window (and everything which went into making it) plus the total amount of money in existence. These concepts are known as “that which is not seen”. In the case of proposed taxation to reduce income inequality, a redistribution of wealth is the seen, while a reduction in spending by those who are taxed, as well as the cost and labor to administer and collect such taxes, are the unseen.

In a similar manner to Bastiat's parable, government actions involve the seen and unseen. Politicians love to tout spending on new infrastructure projects, military hardware, and welfare programs; these things grab voters' attention in the present. However, politicians often fail to address existing issues, which are much less glamorous and draw less attention from voters than spending on new projects.

A perfect example of this was the situation with Oroville Dam in Northern California. Problems with the dam's spillways were known over a decade ago, but politicians chose to ignore spending to fix those problems. They instead chose to spend on supporting illegal aliens and new infrastructure projects like high-speed rail lines. The result was a dam whose spillway began to erode due to a lack of repairs, and almost 200,000 people living near the dam were evacuated. New spending is seen, but a lack of spending to maintain existing infrastructure is unseen. Bastiat's concept also extends to expansions of government in general, such as when new legislation is passed to address perceived problems.

Oroville Dam main spillway aftermath

When legislation is passed, governments often require additional bureaucrats to administer and enforce the resulting departments and regulations. New equipment, furniture, utility services, and even buildings are required for these additional bureaucrats to accomplish their tasks. Money for all of this must come from somewhere, and government has no money of its own to spend. Government could raise taxes, but this would be unpopular with large swaths of voters. Rather than risking unpopularity, politicians resort to something far worse than raising taxes – they borrow in the present and place the debt burden on future generations. In addition to paying back the principle, future generations must also pay interest. The near-term results of government policies are the seen while the future interest is the unseen.

Washington DC has seen constant construction over the dacades to meet the increases in government power and spending

What could future generations accomplish with trillions of dollars they wouldn't need to pay in taxes to satisfy government debt and interest? Perhaps they could find cures for cancer? Maybe they could establish colonies on Mars? Perhaps they could, via the private sector and charities, reduce the perceived effects of income inequality? Is it moral for those in the present to fulfill their desires and world views by placing future generations into debt? Committing one immoral act to correct what is seen as another immoral situation is not a recipe for a just and ethical world.

Property Rights

Bastiat's parable provides insight into the seen and unseen, but there is also another question which is much more fundamental. This is the question of the morality of taking from one group or individual to give to another. Some believe this is a moral and justifiable action, while others do not. However, most who discuss the subject fail to do so objectively, and so their arguments are open to attack by those who have differing views. How does one go about examining wealth redistribution in a logical manner?

By building on concepts put forward by Bastiat, Nobel Prize laureate Friedrich Hayek, and economist Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe has done just this. Hoppe is an economist, Professor Emeritus of Economics at UNLV, and author. In a lecture given at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Hoppe begins with the example of two individuals inhabiting an island on which there is no scarcity, other than a person's body and the place it occupies. Both individuals have only a single body each, and cannot occupy the same space at the same time. Even on an island where food, water, and other resources are not scarce, conflict between the two individuals is still possible if both simultaneously attempt to occupy the same space.

Given this possibility of conflict, Hoppe continues, some form of rules must exist to prevent conflict. These rules are concerned only with the location and movement of individuals. Hoppe expands upon this concept, bringing it into the real world where scarcity is everywhere. Because of scarcity, rules must exist to avoid the use of scarce resources by two individuals at the same time.

To demonstrate the solution, Hoppe returns to the first example of two individuals on an island. The rule he puts forward simply stipulates that anyone may move their own body to any space they please, as long as doing so does not interfere with the body of another who is already occupying said space. Moving back into the real world, Hoppe lays out four simple rules:

Each individual is the exclusive owner of their own body. Who else should own a person's body? One or more other people? Other people as well as the person whose body is in question?

Each individual is the exclusive owner of all nature’s resources which he has perceived as scarce and put to use by means of his own body before any other individual has done so. Who else should be the owner of a resource if not the first to use it?

Each individual is the exclusive owner of anything they produce with the aid of their own body, as long as such production does not physically damage what is exclusively owned by other individuals.

Transfer of exclusive ownership from one individual to another may only be done via a voluntary and explicit trade and/or contract.

These rules establish and protect the concept of private property, and are designed to prevent and deescalate conflicts. With these rules, the debate over whether it is moral to take from one to give to another moves from the moral realm and into the logical and rational one. We can clearly see that taking what one person has earned and giving it to another is an initiation or escalation of conflict. Conflict is the opposite of what many who advocate for government intervention claim to value – peace.

With this in mind, as well as the discussion of unseen results of government actions, perhaps those who believe government is the solution to income inequality can rethink their position or formulate better arguments for it.

References

Fieldhouse, A. Rising income inequality and the role of shifting market-income distribution, tax burdens, and tax rates. http://www.epi.org/publication/rising-income-inequality-role-shifting-market/

Bastiat, F. La vitre cassée. Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas. http://bastiat.org/fr/cqovecqonvp.html