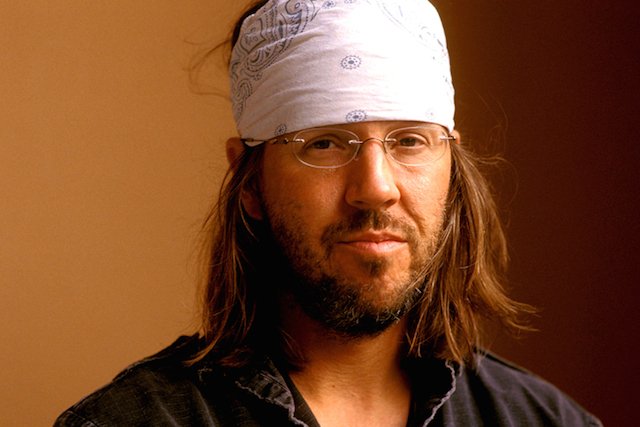

David Foster Wallace on Argumentative Writing and Nonfiction

In December 2004, Bryan A. Garner, who had already struck up a friendship with David Foster Wallace, started interviewing state and federal judges as well as a few key writers. With over a hundred interviews under his belt by January 2006, he called David to suggest they do an interview. So on February 3, 2006 the two finally got together in Los Angeles for an extensive conversation on writing and life that offers a penetrating look into our collective psyche. Their conversation has been captured in Quack This Way: David Foster Wallace & Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing.

Very few things get me more excited than reading one smart person interview another. I mean, we’re not talking TV puff pieces here, we’re talking outright depth with an incisive look at culture.

For context, Garner is the author of a book that, admittedly, I have a hard time not opening on a weekly basis: Garner’s Modern American Usage, which helps explain some of the insightful banter between the two.

When asked if, before writing a long nonfiction piece, he attempts to understand the structure of the whole before starting, Wallace simply responded “no.”

Elaborating on this he goes on to say:

Everybody is different. I don’t discover the structure except by writing sentences because I can’t think structurally well enough. But I know plenty of good nonfiction writers. Some actually use Roman-numeral outlines, and they wouldn’t even know how to begin without it.

If you really ask writers, at least most of the ones I know— and people are always interested and want to know what you do— most of them are habits or tics or superstitions we picked up between the ages of 15 and 25, often in school. I think at a certain point, part of one’s linguistic nervous system gets hardened over that time or something, but it’s all different.

I would think for argumentative writing it would be very difficult, at a certain point, not to put it into some kind of outline form.

Were it me, I see doing it in the third or fourth draft as part of the “Oh my God, is what I’m saying making any sense at all? Can somebody who’s reading it, who can’t read my mind, fit it into some sort of schematic structure of argument?”

I think a more sane person would probably do that at the beginning. But I don’t know that anybody would be able to get away with . . . Put it this way: if you couldn’t do it, if you can’t put . . . If you’re writing an argumentative thing, which I think people in your discipline are, if you couldn’t, if forced, put it into an outline form, you’re in trouble.

Commenting on what constitutes a good opening in argumentative writing, Wallace offers:

A good opener, first and foremost, fails to repel. Right? So it’s interesting and engaging. It lays out the terms of the argument, and, in my opinion, should also in some way imply the stakes. Right? Not only am I right, but in any piece of writing there’s a tertiary argument: why should you spend your time reading this? Right? “So here’s why the following issue might be important, useful, practical.” I would think that if one did it deftly, one could in a one-paragraph opening grab the reader, state the terms of the argument, and state the motivation for the argument. I imagine most good argumentative stuff that I’ve read, you could boil that down to the opener.

Garner, the interviewer, follows this up by asking “Do you think of most pieces as having this, in Aristotle’s terms, a beginning, a middle, and an end—those three parts?”

Congratulations @diamondjungler! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!