Hedge funds see a gold rush in data mining by the Financial Times

Investors seek an advantage from tradable intelligence but legality of alternative data is in question

When Under Armour, the sportswear maker brought to prominence in Oliver Stone’s American football epic Any Given Sunday, reported its latest earnings in early August, it was an unpleasant surprise for many investors.

The company reported a second straight quarter of losses, cut its sales outlook for the rest of the year and announced a large restructuring programme that it warned would halve its operating profits in 2017. The shares tumbled almost 9 per cent on the day and have kept sagging since.

But for some hedge funds that were sold bespoke data on the company, the dismal results might not have been such a surprise. In recent years there has been a proliferation of new “alternative data vendors” that trawl through vast pools of digital information and sell it to investment groups desperate for an edge in markets.

These vendors often scoop up the digital “exhaust” that people, companies and countries throw out through the normal course of their business and turn it into valuable intelligence.

For example, hints of Under Armour’s downturn could have been detected in a decline in job listings on its website, the internal rating of its chief executive by employees on Glassdoor, the recruitment site, or a dip in the average price of clothes on its website. But this is just the tip of the alternative data iceberg, and investors are waking up to the fact.

“In order to generate sustained [returns] investors must embrace the task of acquiring, analysing and understanding the ever-growing data universe,” BlackRock said in a recent paper. “Those that fail to do so run the risk of falling behind in a rapidly changing investment landscape.”

Many of our online activities leave a digital fingerprint. Our mobile phones can be tracked, our emails scanned and our online purchases monitored. Companies release vast amounts of data on their websites and even local and national governments are digitising many aspects of their operations.

The vendors scrape this “big data” — for everything from geolocation details to consumer trends and sentiment analysis — and turn it into tradable signals. Investment groups have often looked outside traditional information sources such as economic data releases or earnings reports. Some now think this digital treasure trove can underpin the future of the money management industry.

However, there is disquiet over the unregulated nature of the industry, which Tabb Group estimates will double in size in the next five years to $400m in annual sales. Some fear information that may appear public may in fact be legally protected, while others worry that hedge funds signing deals for exclusive access to certain valuable data sets will open themselves up to close scrutiny in what is a legally grey area.

“It’s a brave new world,” says Jonathan Streeter, a former federal prosecutor who led the insider trading case against Raj Rajaratnam, co-founder of the Galleon Group hedge fund. Mr Streeter is now a partner in New York at Dechert, a law firm with a large hedge fund client base, where he advises on what data sets are legal to purchase and use.

“I don’t know of a case that’s been brought, but everyone anticipates that there will be one soon and [prosecutors] would like to bring one,” Mr Streeter says. “This is a hot topic. I get a lot of calls from clients.”

This year, a senior executive from the family investment office of Steve Cohen, the billionaire whose SAC Capital Advisors hedge fund was shut down by federal authorities in 2013 over insider trading, was praising “big data” as its new edge over the market.

Speaking at a conference on alternative investments at the London School of Economics, Matthew Granade, Point72’s chief market intelligence officer, bragged that they scrutinise 80m credit card transactions every day. Coupled with satellite images that can scan car parks and geolocation data from mobile phones to show how many people are visiting various stores, the investment group can get a real-time idea of how companies are doing, long before their results are released.

One LSE student asked how all this data could help Point72 if everyone had access to the same information. The answer was exclusivity agreements, Mr Granade said: “The great thing about this area is you can arrange deals where you are the only ones who get it.”

Hedge funds have always sought an advantage, whether by taking executives out for lavish dinners to glean a sense of how their business was doing, or hiring pollsters to conduct their own surveys ahead of elections or referendums. Increased regulation and a crackdown on insider trading have reduced some of those avenues, but alternative data can offer different routes.

The biggest challenge for investors is the sheer extent of how much digital information is generated every day. There are more than 1bn websites with more than 10tn individual web pages, with 500 exabytes (or 500bn gigabytes) of data, according to Deutsche Bank. And more than 100m websites are added to the internet every year.

To help navigate through the morass, an expanding range of companies offer to scrape, clean and sell this data to the investment community. They sit between the generators of information — such as app stores, telephone and credit card companies or social media sites — and the buyers of the data.

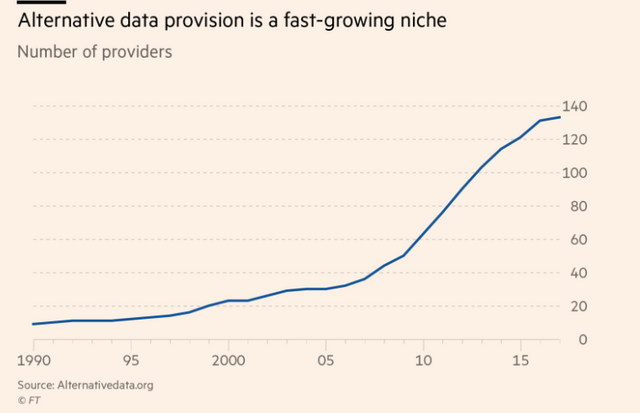

Alternative Data Insider, an information provider backed by YipitData, one of the vendors, has counted more than 100 companies in the field, with money pouring in. SpaceKnow, a satellite imaging company that looks for clues on economic activity in China and Africa, raised $4m this year, while Prattle, a sentiment analysis company that uses artificial intelligence to turn material such as central bank speeches into tradable intelligence, raised $3.3m.

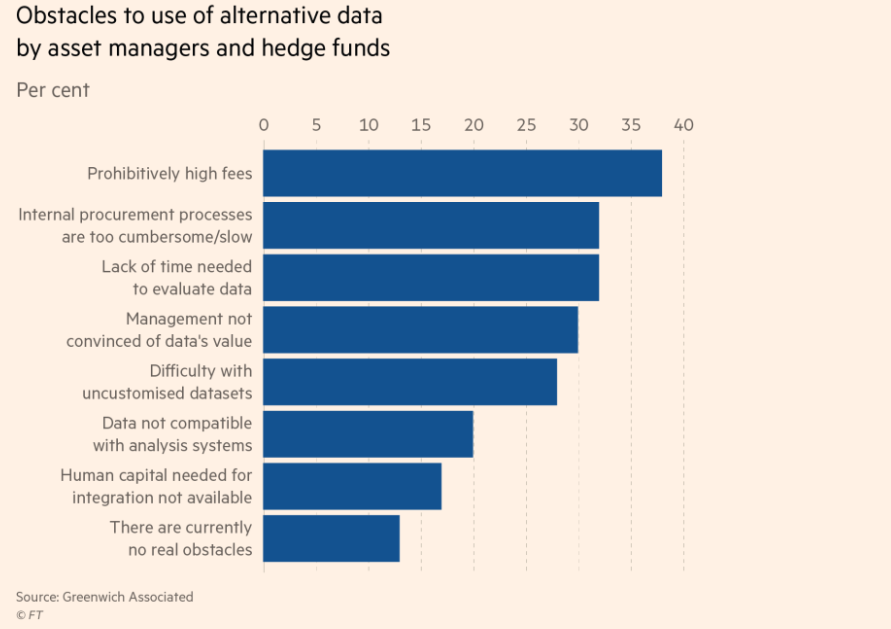

“Alternative data will only be alternative for so long, eventually becoming a core part of any portfolio manager’s toolkit,” Greenwich Associates, a market consultancy, wrote in a recent industry report.

There is no suggestion that any hedge fund or alternative data vendor are doing anything illegal by using these new digital data sets. But lawyers urge caution, arguing that some aspects of the business, such as how providers collect the information they sell to hedge funds, and whether it is legal for funds to enter into “exclusivity” agreements with providers, are attracting the interest of regulators and prosecutors concerned that hedge funds are getting an unfair market advantage. The laissez-faire attitude of some of their colleagues and parts of the data vendor community is also under scrutiny.

Hedge funds also worry that some vendors do not do a good enough job of scrubbing personally identifiable data from their troves of information. Many therefore have dedicated internal teams that clean the data before it is involved in the investment process. Indeed, some hedge fund managers say they would welcome federal regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission taking a closer look at alternative data.

“It’s like the Wild West and ultimately it will come under the purview of the regulators,” says one fund manager, who says legal opinions on the subject vary. “I have yet to see a clean legal opinion on all this. And we’ve looked for one.”

Hedge funds have good reason to be wary. After a series of arrests from 2010, the industry was upendedwhen dozens of traders, portfolio managers and analysts were prosecuted for using information they gleaned from so-called “expert-network” companies which, like data vendors, tried to match investors with information.

The Wall Street traders used company insiders, doctors and others to expand their knowledge of industry trends or companies. The authorities cracked down when traders got their hands on confidential information, such as unpublished drug trial results.

To break insider trading rules an individual needs to act on “material, non-public information” received in violation of a duty to keep it confidential. While lawyers say the data sets sold must be material by definition because an investor is willing to pay for them, the vendors typically have permission to sell the aggregate data once a user clicks the box agreeing to terms and conditions. But with few legal precedents and different standards between countries or even states in the US there is little clarity.

Mr Streeter of Dechert believes it will probably be a high bar for prosecutors to bring insider trading charges against funds that have used data not deemed to be public. For instance, mobile geolocation data, which can show how many people visit Walmart, Sears or Ralph Lauren over a given period, could well be viewed as material information, and if 50 hedge funds pay say $100,000 for exclusive use of the data, it would be hard to argue that it is public. The crux is whether the owners of the information, such as AT&T or Verizon, have received consent from their customers to sell it on to third parties, he says.

“You look in the small print and there’s probably somewhere in there that says Verizon can sell that data. Verizon would then sign an agreement with a data provider. So under US law [there would be] no breach of duty, no insider trading,” the former prosecutor says.

Many more vendors scrape information from websites, and even if it is in the public domain lawyers say they may not always have the legal right to sell it on to third parties.

Rado Lipus, head of Neudata, which vets data sets on behalf of investment groups, says “exclusive data sets are a double-edged sword”. While they can be profitable, they are clearly not public data and some investors — especially bigger ones — prefer to avoid them to avert even a whiff of controversy. Several large hedge funds such as Man Group and AQR Capital Management go further, saying exclusive data sets are not worth the expense or legal risk.

Lawyers say they are advising clients against using some data sets, given the legal and reputational damage even the slightest sense of impropriety could cause. But experts believe the greatest risk of prosecution comes from the New York attorney-general, Eric Schneiderman, who is tackling financial fraud under the Martin Act and could stop hedge funds from using exclusive data. He has intervened before. In 2013, under pressure from Mr Schneiderman, Reuters stopped providing some exclusive content to its premium subscribers.

Sandy Rattray, chief investment officer of Man Group, says he has at least two people a week offering him exclusive data, but that it is too expensive and in any case they would analyse it differently than other funds. “There’s a gold rush in data mining,” he says. “Most people that went off to prospect for gold came back penniless, but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t any gold.”

Follow @jessethan for more articles like this!