On the Difference Between Utility Tokens & Security Tokens

Recently, much of the "brain hash" in the blockchain industry has been devoted to the demise of ICOs (initial coin offerings) and the seemingly inevitable rise of STOs (security token offerings) that is to come in the as-yet-undeterminable time frame of "some time soon."

The Great ICO Bust of 2018 has been largely blamed on what is essentially the file format of the majority of the tokens that were sold in ICOs to raise funds for projects. It has gotten to the point where the very concept of utility tokens has come under fire. Many pundits now claim that the utility token is dead and will never rise again. My favorite new crypto jargon these days is futility token.

However, correlation is not always causation. Utility tokens did not cause the collapse of the crypto markets this year. Insider trading, outright scams, the lack of proper risk management, the inevitable unwinding of a hype cycle, the Tether hypothesis, the impact of bitcoin futures, and more... All of these reasons are more obvious and more direct causes of the approximate 90% collapse in prices across the board for all cryptographic assets seen in 2018. Increasingly, however, especially within the context of the stock market's recent Santa Claus Folly, I'm leaning more and more towards the "canary in a coal mine" scenario. If that is indeed the case, then there was nothing any one blockchain person or entity could have done to avoid it.

Let's not blame the messenger though. In this environment, that's all the poor little utility token was - a fleet-footed Pheidippides warning us all to take off our rose-colored glasses and start to clean house before digital tokenized assets on the blockchain become a legitimate asset class warranting a significant part in investor portfolios all over the world. And if you buy into the "canary" argument, you'd have to thank bitcoin for warning us all to get our financial asset portfolio "ducks in a row" before the shit truly hit the fan.

But let's be very clear about the distinction between utility tokens and security tokens going forward. Security tokens are great, but by no means are they revolutionary.

Utility tokens, on the other hand, still have the capacity to reshape the digital world we live in for the better of all mankind. Security tokens, in what will most likely be their most prevalent use case, are basically just digital stock certificates.

Cool and useful? Yes. Revolutionary? No.

I don't know. You tell me. But I'm thinking that might be an opinion that is a little bit out of tune with the rest of the industry these days. So please allow me to explain.

Why Are Utility Tokens Still So Important?

Utility tokens offer the hope of redefining the way ownership of a network works forever. In today's equity-based environment, the gains due to the private ownership of a successful closed network or platform business accrue solely to the equity holders. Users are subject to monopoly pricing power and at-times authoritarian regulation.

Closed network ecosystems do not maximize economic value.

Closed network ecosystems almost always allow too much power to accumulate to one participant, eventually that will be to a single node in the network. There are users and there are owners and never the twain shall meet. A user may use that platform in order to transact as either a platform buyer or a platform seller. But in either case, they are a platform user that endeavors to exploit said platform for their own economic benefit by engaging in economic activity, the profit from which mostly accrues to the platform owner, though there may be just enough of a "taste" provided to the user to keep them engaged.

This type of closed system incentivizes the platform users to engage solely in pure profit-seeking behavior. However, in game theoretical terms, because platform owners must also make this base assumption, they must also engage in profit-seeking behavior, the result of which, in the long run, hampers the growth of network activity. In short, the economic incentives are not the same for a platform user as they are for a platform owner. This inequity results in massive economic inefficiency. Thus, closed network ecosystems do not maximize economic value, but they can maximize it for the one player in the ecosystem that may achieve monopoly status.

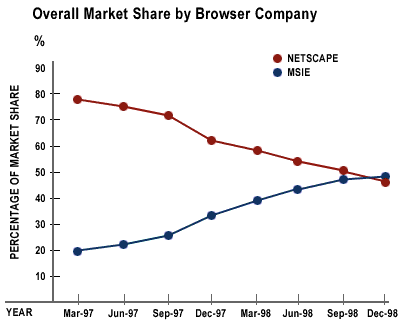

At the very least, growth is sacrificed for control. Perhaps the most famous example of a monopoly owner of a closed network system is the famous Browser Wars of 1995 to 2001. In this case, Microsoft exerted its control over the ecosystem to the detriment of the ecosystem's growth but to the benefit of the monopoly owner, Microsoft.

In this lockdown dragout battle from the Internet Bubble era, the open-source browser software Netscape Navigator held an IPO, almost immediately tripling its valuation to $2 billion. But the company still lacked the cash reserves and OS domination of rival Microsoft. Thus, when Microsoft introduced a browser of its own, the even-to-this-very-day notoriously flawed Internet Explorer, Netscape despite having a superior product of its own, eventually could not compete against its pre-installed and freely distributed browser competitor.

Why? Microsoft operated its own closed network ecosystem, the Windows operating system (OS). That OS commanded more than 90% of the pre-install market for newly manufactured computers. Basically, they controlled what software got bundled onto PCs without actually having to produce those new machines themselves. As you would expect, the margins were redonkulous. However, this practice would quickly land Bill Gates' company in hot water with the Department of Justice and a protracted five-year-long battle with superlawyer David Boies in one of the most famous anti-trust cases in the history of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890.

The result was a relatively swift kill by IE over Navigator. The monopolistic interest had no interest in letting a valuable business (the internet browser) camping out and flourishing in its pre-existing monopoly ecosystem (the Windows operating system).

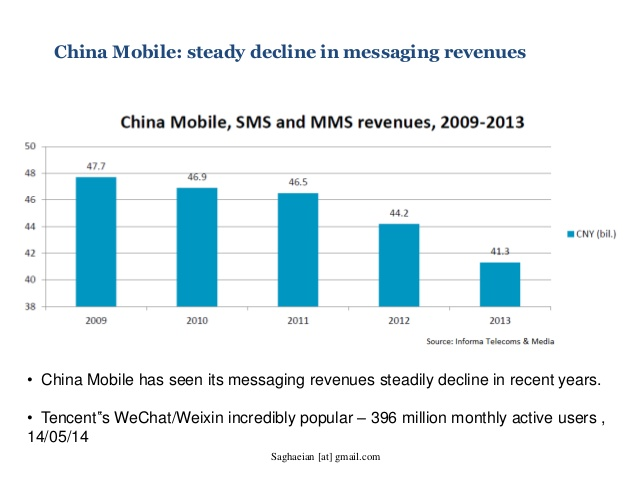

We see these kinds of epic struggles over market share every once in a while in our technology cycle-driven lives. The last one I remember clearly was the argument surrounding the struggle between China, a country that basically owns its telecommunications industry via a triumvirate of nationalized behemoths, and Tencent, a fast-growing Chinese tech firm that plays by the Party rules in order to safeguard its status as "national champion" of IT and all that is not e-commerce in the Chinese Web 2.0. Back in 2011, when its now flagship app WeChat had just been launched, it siphoned off a key piece of revenue for the closed network operators of China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom. They had been used to billions of dollars in annual revenue from SMS fees. Yes, that arcane practice of charging per text (or even per character!) to people who want to communicate with one another. But WeChat was about to end that game with its over-the-top (OTT) network services.

When WeChat first came on the scene, the Chinese government's telecom triopoly tried to force Tencent to pay compensation for this displacement of revenue. In the end, the effort stalled and the Chinese telecom industry vowed to reorganize as a more efficient pseduo-monopoly, realizing that the 4G, and soon to be 5G, closed networks that they operated would serve as the backbone for all future tech innovation in China. If those Chinese telecoms were not state-owned enterprises (SOE), and thus willing to operate within the bounds of what's best for the country's economy (at least some of the time) rather than what's best for their company, rest assured that they would not have given up such a battle so quietly. See AT&T, its forced breakup, and eventual reassembly for an example of how a more purely capitalist enterprise would have responded.

An example of how capitalist monopolies in control of closed network systems work to deter innovation that Western readers might be more familiar with is the classic story of Zynga versus Facebook.

With its flagship game Farmville, this online gaming startup took advantage of an API Facebook initially released in May 2007. Ironically, the API had initially been a part of Mark Zuckerberg's kill move on Myspace. Hey, I just went to check and see if Myspace still had a website and, yep, it does! Isn't that amazing?

After Zynga growth hacked its way to something like 100 million DAUs (daily active users), Facebook aggressively moved to cut off the fuel that fed Zynga's growth after negotiations broke down after the implementation of Facebook Credits. Eventually, however, Facebook would reduce the amount of insidious messages on its platform by 95%, in the name of fighting spam, but it could just as well be characterized as starving Zynga of potential new users. The software company with the cute bulldog logo almost starved to death.

With a post-IPO peak valuation of nearly $13 billion in 2012, Zynga (ZNGA) trades today at a little less than $3.5 billion, which is still about double the value it fetched at its all-time low back in early 2016. Meanwhile, Facebook (FB) traded at its all-time low in 2012, at around a $50 billion market capitalization. Earlier this year, in 2018, FB traded at an all-time high of over $600 billion.

I'll just leave those numbers right here again. ZNGA - $3 B; FB - $600 B.

I can't think of a better argument than that for opting to support the development of open network economies. Just think of how much better we could have made Farmville if only Facebook would have let us innovate! Well, I realize that my last sentence might not exactly persuade you of my argument, but i hope you get my meaning.

The stories of Microsoft & Netscape, Facebook & Zynga, as well as the anti-story of China Mobile & WeChat all illustrate why closed network economic systems are so dangerous. And why the growth of open-architecture network systems, driven by utility token adoption, is so god damn important.

In contrast to the easily exploitable "walled garden" approach to network economics, a well-designed and well-operated open utility token economy creates a third class of economic actor, a user-owner if you will, to add to the previously mentioned classes of user and owner. In theory, such a user-owner would engage in economic behavior that would emphasize long term returns over short term. Introducing this economic actor into an economic system should help to balance the inherently short-term nature of the user/owner dialectic. In other words, giving early adopters some "skin in the game" while simultaneously diluting the power of the capitalist technocrats ("You gotta have someone to pay for it and someone to build it!") at the heart of any network economy may in fact be the key to solving a whole host of technological issues related to cybersecurity, efficiency, and asset monetization.

The friction between owner and user that is everpresent in a closed network economy just isn't there in an open network economic ecosystem. In addition to injecting into the system an increasing amount of hybrid economic actors with stabilizing long-term economic time horizons, open token networks remove this friction by aligning all network participants to work together toward two common goals:

- the growth of the network and

- the appreciation of the token.

Most importantly, they offer society the best chance to resist the over accumulation, or centralization, of power at any one particular node in an emerging economic ecosystem.

So please don't pooh-pooh on utility tokens (UT) any more than you have to. They are not the problem. Assuredly, there are going to be some UTs that will emerge from this crypto winter that become very, very valuable. Other UTs will, inevitably, die. But they won't have died because the concept of the utility token is inherently flawed. They will have died because the design of their particular utility token was flawed.

In the end, UTs may only represent future access to a company’s networked product or network service (not equity). But given that 70% of tech value is driven by network effects, that could easily become a very valuable access token in the long run.

UTs are not designed as investments and they should never have been even confused with securities. They are simply the fuel to engage in transactions on a specific network. Therefore, they should be exempt from securities laws. Though, in effect, they are a form of regulation upon their respective networks in and of themselves, should governments believe that UTs still deserve regulation, they could work towards a body of legislation specific to the nuances of utility tokens and not try to shoehorn them into existing regulatory policy. But these things take time, of course.

In short, security tokens (STs) are great, but they aren't the bee's knees like utility tokens have the potential to be. STs may represent equity in a company or some other asset and offer many substantial benefits to tokenholders. There are a lot of reasons to like them (which I will reserve for another post). But let's make this clear:

I much enjoyed reading this article that provided a new insight into the mechanics of utility tokens. I still have not fully understood the potential impact of STs and their interface to the real world. How will owners behave if they, for instance, own 1 ppm (part per million) of a hotel or a ship? Will they vote?

Yeah, that's what I think I'm trying to get at by making the distinction between being an owner and a user-owner. In your example, the ST holder is just an owner as they most likely are not a user (and if they are, not regularly) of a hotel or ship. Thus, in order for them to care, their ownership level must pass a certain threshold, let's call it the DGAF level, before they act like, well, they GAF. One might call this the ”skin in the game" hypothesis.

A user-owner, on the other hand, would have a comparatively much lower threshold for their DGAF level, simply by virtue of the fact that the value of something that someone uses regularly is comparatively higher than the value of something that they DO NOT use regularly. This proposed relationship one could call the ”out of sight, out of mind" hypothesis.

Thanks for this article on security and utility tokens. I am reading and hearing more about the 2019 onset of security tokens and it is nice and refreshing to see the alternative side, making the case for the continued development and use of utility tokens.

Very useful info! Thank you!! Upvoted!

Interesting article, I think this coming year 2019 will be very interesting in terms of utility tokens and security tokens as many platforms are getting ready to launch, some early in the year and some a bit later and then there will always be new start ups coming and going too. Thanks for this informative and insightful post and all the best in 2019.

Yeah, we’ve been hearing a lot about these ST exchanges “coming soon” for a while now. Can’t wait to actually see one for real in the wild!

Posted using Partiko iOS

Adorable post

Adorbs, huh?

Posted using Partiko iOS

I wonder if we will see the same boom with STO's as we have seen with ICO's in 2016-2018. Most of the Initial Coin Offerings in 2018 ended up bad for investors. Great article!

If you mean by “boom” that maybe STO’s will garnish 100x returns like some of the ICO’s saw, then no, I don’t think that will happen.

But in terms of sheer numbers we might see exponentially more security tokens (though mosy likely their returns won’t be so exponential) with much more modest raise targets in 2019-2021.

That’s just what I think, though. Thanks for reading!

Posted using Partiko iOS

True, security tokens are more an evolution of what's there already, while utility tokens are a game changer. Let's see if 2019 is ready for some first usecases and more adoption. Happy 2019!

Happy new year to you, too! @sambor Of course I don't know the answers either. I just know I can write down what I think about these issues and hope that greater minds than mine will figure out the best way forward. I'm glad that at least one person, you, still holds out hope for utility tokens.

If you think about it, the very concept of the supra-national cryptoeconomic unit that is the utility token may be the most important innovation in the whole cryptocurrency IP portfolio. Bigger than any technological or even any other conceptual component.

Thank you so much for participating the Partiko Delegation Plan Round 1! We really appreciate your support! As part of the delegation benefits, we just gave you a 3.00% upvote! Together, let’s change the world!

@shanghaipreneur purchased a 58.32% vote from @promobot on this post.

*If you disagree with the reward or content of this post you can purchase a reversal of this vote by using our curation interface http://promovotes.com

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.