The fight against inflation can sink the economy

Inflation was already skyrocketing in Europe and the United States long before the Ukraine war, and international organizations had begun to worry seriously before Christmas.

And that was a novelty, because until November they had mistakenly expected prices to land, during the first half of 2022, with the remission of the global supply crisis, the dilution of the impact of the large stimulus programs, the withdrawal of the massive purchases of bonds by central banks and the first rises in interest rates.

The best way to understand the present is to know our past.

It was a tasty prospect for many politicians, because they thought that from now on they could blame inflation on the central bankers who were fighting it, even though they had helped cause it, and continued to stoke the fire further, with huge amounts of public spending.

In parallel, the coffers of the States, greatly depleted by the pandemic and the stimulus plans, were not bad at all with unleashed inflation, as long as it was temporary. If prices go up a lot, the collection of some taxes such as VAT also gallops with joy. And not only that: if prices devalue our savings in the bank, they also devalue the amount of sovereign debt over GDP; and if interest rates, like now, are rock bottom, both the population's mortgages and the credits requested by the States (through Treasury bonds) are cheaper.

The plan falls apart

Many politicians were confident that, since these crazy prices were going to be transitory, they just had to have a little luck so that they did not coincide with big electoral periods.

Population would forgive their impoverishment, because economic growth and employment would continue to show splendid figures, and, with the passing of the months and the help of this or that last-minute controversy, the bad experience of inflation would be forgotten.

The problem with this "great plan" is that, as some critical economists, such as Mohamed El-Erian or Larry Summers, had been warning, it was almost a letter to the Magi. And not only did time prove these economists right before Christmas, causing the Federal Reserve to abandon the idea of the transience of inflation at the end of November, but soon after, new reasons for concern were added with the preambles and, finally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

On January 18, the United States openly acknowledged that the attack was imminent and, two months later, with the war underway, the reference barrel of oil in Europe, Brent, had already catapulted from 90 to 110 dollars.

Indeed, one had to look under the rocks for analysts who did not believe that high inflation was going to be a long-term problem, that energy was going to be one of its main drivers and that the combination of galloping prices and the ferocity of the measures necessary to contain them could lead to recession in the countries with the most uncontrolled prices, including Spain and the United States.

Larry Summers, a critical economist and one of the architects of Obama's economic measures, has spent months recalling, from his podium at the Washington Post , that the last point-blank fight against inflation ended with the recession of the American economy in 1980 and 1982 What Summers is referring to is the phenomenon known as the Great Inflation, which began in the mid-1960s in the United States and did not subside until the 1980s.

And perhaps what may worry economic historians most is that that period rhymes with ours.

Dangerous rhymes

Let us remember that our crazy prices began almost a year ago and that now the increase generated by the war in Ukraine will add its momentum.

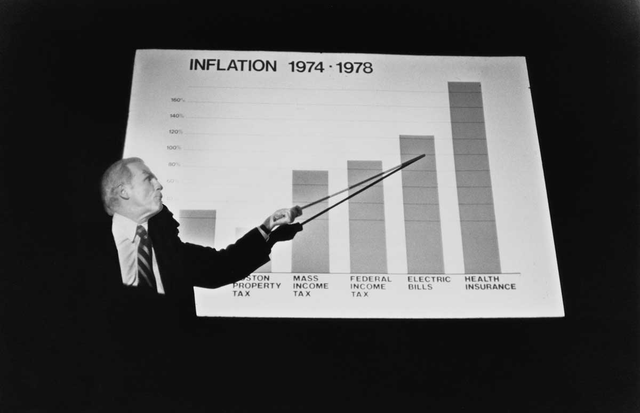

Prices were already rising too high in the United States before the mid-1970s, when the oil shocks following the Yom Kippur War exacerbated a very dangerous trend. In 1968, inflation was already growing by almost 5% per year and only advanced by less than 4% in two of the thirteen years from 1968 to 1981.

Furthermore, both in the 1970s and now, economists agree that the central bankers either arrived or have arrived too late to fight rising prices without damaging the economies of the countries most affected by inflation. And pay attention to this: if, as it seems, the Russian invasion and the sanctions adopted give a strong bite to economic growth in the first half of this year, the central banks may end up delaying even more the intervention demanded by the economists and having to take even more drastic measures afterwards.

The origin of the Great Inflation was multiple, but, among the most decisive engines, four stand out: first, the excessive tolerance with the increase in prices by the Federal Reserve, which was almost exclusively concerned with full employment, and the poor quality of the statistical data used to design its policies; second, the increase in public spending with the Vietnam War and the enormous social programs of Lyndon Johnson; third, the collapse of Bretton Woods, culminating in Richard Nixon leaving the United States from the gold standard; and fourth, and as a grand finale, the oil crises.

Another aspect that rhymes with that time is that, just as politicians today have not really worried about inflation until we have reached pre-pandemic employment figures, politicians back then were not too concerned about rising prices while employment figures were acceptable for the vast majority of the population, which in the United States, as minimal protection was offered to those who lost their jobs, meant less than 5% unemployment.

Unfortunately for the White House, when inflation began to run wild, the objective of full employment was also lost, because only in one of the eleven years between 1970 and 1981 did we find unemployment equal to or less than 5%.

The assassin of governments

And it was around this time that economists and politicians learned a bitter lesson: you can't fight a powerful rise in prices without hurting jobs and growth, and you can't delay the fight too long, because prices exorbitant will also hurt growth and employment and will require painful measures later. Either path has an electoral cost.

That is the reason why Richard Nixon deployed, between 1971 and 1974, a reform to raise the minimum wage in the United States, to protect the working poor, and decreed the freezing of prices and wages of the rest, something that contained a little inflation, but at the cost of creating food and energy shortages.

After its fall from the Watergate scandal, the Ford administration tried to encourage voluntary saving, something that also did not keep prices in check.

The only thing that really worked was that, thanks to the fact that inflation had become one of the great concerns of Americans, the Federal Reserve was able to stand up to it, especially after 1978, with spectacular increases in interest rates, which went from less than 7% in 1977 to an impressive 18% in 1980, and printing fewer and fewer banknotes.

That led to prices rising from a whopping 13.3% in Voters made Carter pay for his fight against inflation, a fight that continued during Reagan's term with the same Federal Reserve Chairman, Paul Volcker, who had declared war on prices in 1979 and who would not leave his post. as head of the Fed until 1987.

For all these reasons, we should not be surprised by the fears now running through the White House and the European chancelleries of the countries hardest hit by rising prices. Politicians know that high and persistent inflation often heralds a recession and that both phenomena can end up putting them out of work.

People is still focused on the tragedy in Ukraine, but how long will it take to turn their eyes towards their governments?1979 to a bearable 3.8% since 1982.

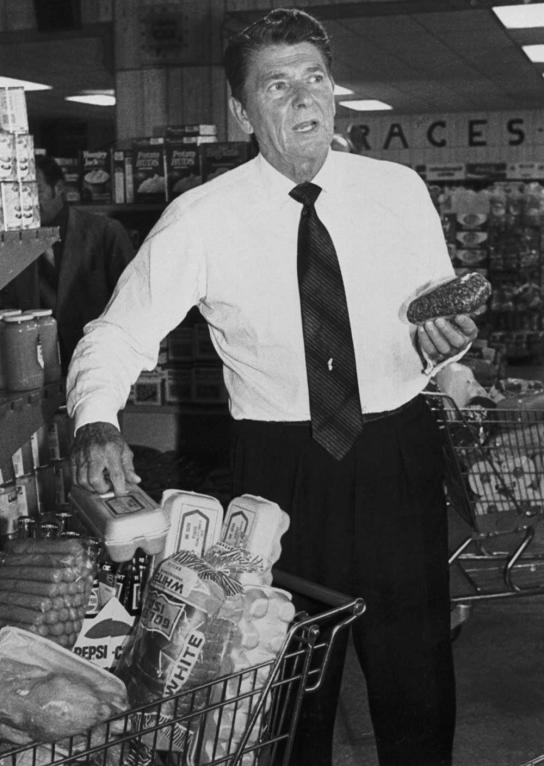

But, despite the success, the consequences of those measures paved the way for Jimmy Carter to lose the White House in the United States, because Ronald Reagan blamed him for the 1980 recession, for prohibitive interest rates to contract loans and mortgages (buying a house was like climbing Everest) and unemployment that increased by 40% between 1979 and 1981.

Your post was upvoted and resteemed on @crypto.defrag