1982 GOTO 2017

Michael Carroll, 20170615

The Sinclair ZX Spectrum home computer was launched in the UK on April 23rd 1982, thirty-five years ago. Though it was only one of many home computers on the market in the early 1980s, it was arguably the most influential.

Its predecessors – the ZX80 and ZX81 – had been pretty influential too. Simple, cheap and “reliable-esque” they helped introduce computing to the masses. They sold in great numbers – over 1.5 million in the case of the ZX81 – but home computing was still considered a niche hobby, until the Spectrum came along.

Boasting 48 kilobytes of RAM (16KB for the smaller, slightly cheaper version – which was the only one I could afford at the time), a 3.5mhz 8-bit processor and a screen resolution of 256x192 pixels in sixteen colours (well, sort of – but that’s a whole ‘nother story for another time), you might be thinking that the Speccy was staggeringly primitive by today’s standards. I mean, these days, 48KB would be regarded to be on the small size for an icon.

It also had 16KB of ROM, which held the entire operating system plus the Spectrum BASIC programming language. BASIC stands for “Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code”: it’s a simple language designed to easily introduce the user to standard computing concepts. Almost every computer of the era had its own version of BASIC. (The Jupiter Ace – a Spectrum-lookalike created by many of the same engineers – used the language Forth instead. I never understood that decision: sure, Forth is way more powerful and flexible than BASIC, but it’s very tricky to learn.)

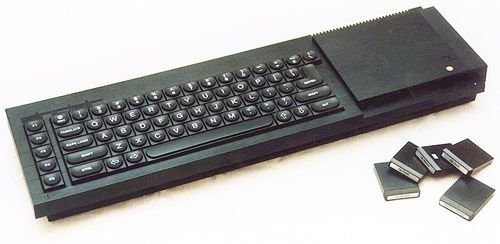

The Spectrum proved to be extremely popular, with something in the region of five million units sold, but like its older siblings tended to be looked down upon by the more snobby computer magazines of the time (a note to young people: “magazines” were the equivalent of the Internet back in the 1980s – your mommies and daddies will explain), mostly because of the 40-key rubber keyboard.

Yes, the learned computer journalists in the early 1980s were frequently just as petty and snide as many of their current counterparts are about Macs or PCs. (I’m a long-time PC user so I don’t know enough about Apple computers to be appropriately snide about them, but I do understand that many people consider Macs to be superior to PCs. I believe that there are support groups available.)

The Spectrum’s chief rival – at first – was the BBC Micro, built by Acorn Computers and badged by the British Broadcasting Corporation who wanted to get in on the home computer revolution. It featured a real keyboard, better graphics, more ROM, and it looked like a computer, so it was lauded as being somehow better, chiefly on TV shows made by the BBC. It was also – and this is a very important point – considerably more expensive, costing £235 for the base model: the Spectrum cost £125 at its launch, which dropped to £99 after a few months.

But the Spectrum’s affordability was not why it was so influential…

The Spectrum was relatively easy to program. OK, so it had a very idiosyncratic method of entering commands (a subject for another time, I think!), but once you got used to that it was plain sailing. The manual was excellent: A novice user could be writing her own simple programs within minutes. And, if she kept at it, pretty soon she would have mastered the Spectrum BASIC and be looking around for something with a little more kick.

That’s where machine code came in. Machine code is the language at the heart of a microprocessor. On the Spectrum, as on most computers of the time, the BASIC language was interpreted. What that means is that the processor has to decipher each BASIC command before it can act on it, which can be time-consuming, especially when the same command is called over and over – the processor has to decipher the same thing each time.

One way around that is to use a compiler. This does pretty much the same thing as an interpreter, except that instead of deciphering and executing the commands one at a time, the compiler creates a whole new version of the program in machine code. This can be run many times without the need to re-compile unless the source program has been changed. Typically, a compiled program on the Spectrum would run about ten times the speed of the interpreted version.

But that’s not quite good enough, because even though the compiler creates machine code, it’s not going to be tremendously efficient. A lot of us Spectrum programmers taught ourselves how to write the machine code directly, because it resulted in much faster and much smaller programs. When you’ve only got 16KB to play with – and about 7KB of that is swallowed up by the screen memory – every byte counts.

(Think about the scale of this for a second, boys and girls: Say the average Spectrum had 48 kilobytes of RAM. That’s 49,142 bytes. With five million Spectrums sold, that’s 49,152 x 5,000,000. Which comes to 245,760,000,000 bytes of RAM in all the Spectrums ever. The PC on which I’m writing this article has a 2-terabyte hard drive. It could store the contents of all the Spectrums ever sold nine times over.)

The mark of a real programmer is one who will spend hours optimising a program in order to shave a few seconds off the run-time. Yes, that was me. I reckon I spent most of 1983 and 1984 counting clock-cycles and inventing ever more efficient algorithms that I knew I would never have a reason to use in real life. Especially because back in those days I was a postman.

Nowadays, PCs are so big and so fast there’s very little need for someone to write native machine code: all the big programs are written in C++ or something based on it. If a programmer wants to put a list of names into alphabetical order, she calls the “sort” routine, one of thousands of pieces of code built into her compiler’s library. She doesn’t ever need to know how the sort routine works, only that it does. Shame, really… Back in my day we did everything the hard way, partly because there was no alternative, partly because we were making it all up as we went along.

But I’m not here to complain about how the average modern programmer doesn’t know his registers from his stacks, tempting as that is. I’m here to talk about how cool the Spectrum was.

See, because it was easy to program, countless little back-bedroom companies started up, the vast majority of them writing games. Within a couple of years, the Speccy had lots of games. And by “lots” I mean tens of thousands. Most of them were rubbish, of course, but some were incredibly successful and made their programmers lots and lots of money.

The hardware industry got a boost too. The success of the Spectrum was so great that within a year of launch there were hundreds of third-party peripherals available. Admittedly, most of these were joysticks, but there was other cool stuff: speech synthesizers that made your Speccy sound like an asthmatic Dalek in a wind-tunnel, replacement keyboards that enabled the user – in one swift, easy move – to completely invalidate the computer’s warranty, a power-switch (the Spectrum didn’t come with one as standard: you had to plug it out at the wall to turn it off), and little plastic wedges that you could use to prop up the back of the machine to give it a more natural typing angle (yes, really: they were marketed as “ZX Feet” if I recall correctly – almost every Spectrum-compatible piece of hardware was called “ZX-something”, much in the manner of every current Apple-compatible piece of tat having a little “i” appended to the start of its name).

But the software industry was where the really exciting stuff was happening… hundreds of new software companies were formed, most of them producing games, and some of those games pushed the Spectrum far beyond anything its designers ever imagined.

One such company stands out above all the others, in my opinion. That was Ultimate Play the Game.

Their first four releases were for the 16KB Spectrum – Jet Pac, Pssst, Trans Am and Cookie – and right from the start it was clear that they were several cuts above the average company. The games were simple but tremendously addictive, with neat graphics and – for the Spectrum – rather good sound. The next two releases – Lunar Jetman and Atic Atac – were more ambitious, aimed at the 48KB model, and they, too, were smash hits.

Every Ultimate Play the Game release was eagerly awaited by the fans. And unlike most of the software companies of their time, Ultimate didn’t court the press. They almost never gave interviews. Some companies, like the now-infamous Imagine Software, had press officers and marketing people, and they spent huge wodges of cash on advertising. They routinely made a lot of noise about how amazing their games were. They attempted to make superstars out of their programmers. Ultimate didn’t bother with any of that: they put all their energy into their games. They didn’t announce anything until it was actually finished and ready to go.

The upshot of that is that we, the eager public, had no clue what was coming up until the adverts appeared in the magazines, and even then we didn’t learn much, as this advert for Sabre Wulf illustrates.

See? That’s all we got. The name of the game. No pre-release demos, no screenshots, no nothin’. Just the logo. And it worked… I was so anxious about the next Ultimate release that when I saw the Sabre Wulf advert I actually had heart palpitations.

Sabre Wulf was great, a huge game with lovely big colourful graphics that effortlessly zipped about the screen.

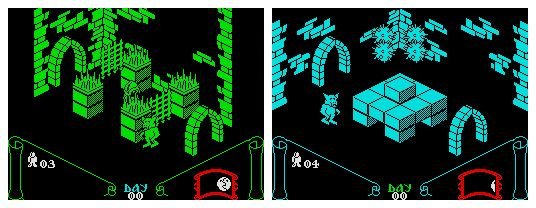

But it was nothing compared to what Ultimate gave us a few months later: Knight Lore. Again, there were no press-previews or announcements, so the only thing we knew about it was the name, until we bought the game, brought it home, loaded it up and started to play...

Knight Lore wasn’t the first Spectrum game to use isometric 3D (that was 3D Ant Attack, released a year earlier by independent programmer Sandy White) but it was the first one that actually looked good. The complexity of the programming – and the speed at which the game ran – absolutely blew everyone away. Remember: in those days there were no dedicated graphics cards or anything of that nature. Everything you saw on screen was there because the programmers themselves worked out how to put it there.

Years later, when Ultimate’s co-founder Tim Stamper gave one of his rare interviews, he strongly hinted that Knight Lore had actually been finished before Sabre Wulf – but they chose to hold off on its release because the market just wasn’t ready for it. In other words, they were so far ahead of their competitors that Knight Lore would have utterly destroyed them. Imagine if today Toyota announced a flying car that was one hundred per cent safe, was fuelled by sea water and cost the same as an ordinary family car… Wouldn’t that be great? I’m not saying that Knight Lore was as big a technological leap as that, but it was still pretty darned impressive.

Sinclair Research, the company behind the Spectrum and its predecessors, made a lot of money very quickly, and the man behind the company, Clive Sinclair, became famous. A natural inventor, Sinclair had already created one of the earliest pocket calculators, one of the first digital watches (again, kids, ask your parents…. or grandparents), and a hand-held TV set that actually nearly worked.

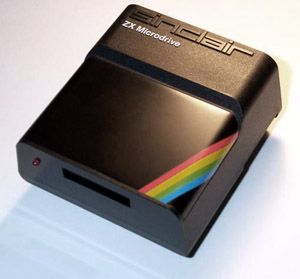

But not everything he released was as successful as the Spectrum. First off, the Speccy’s official peripherals (as mentioned before, there were hundreds – if not thousands – of unofficial ones) were great on paper but decidedly less great in reality, like the ZX Microdrive. Back in those days home computers didn’t have internal storage like hard drives, and even floppy disks (more accurately described as rigid squares, just in case you’re ever tempted to track one down in your local Museum of Computing) were far too expensive. The only affordable mass-storage system we had was the humble cassette recorder.

(Floppy disks, cassette recorders… Crikey, I’m really dating myself now! Which is ironic in a way, because back in the 1980s no one would date me. Sigh.)

The user connected the recorder to the computer and pressed “Record” (more accurately, we had to press “Play” and “Record” at the same time) then instructed the computer to “save” the data or program that we didn’t want to lose forever. The computer recorded a series of high-pitched noises onto the tape. Imagine a Scrillex track in a blender, that’s what it sounded like. Later, when we wanted to re-load the program, we played the tape back. After first rewinding it of course.

The ZX Microdrive did pretty much the same thing, but used a special tape cartridge instead of a standard cassette. The Microdrive was able to read the tape at a much greater speed than a cassette, plus the tape inside was a single loop, which meant no fiddly rewinding back and forth trying to find the start of the program. Each cartridge stored a massive 85KB of data – enough for two full-sized programs.

Trouble was, the Microdrives weren’t exactly reliable. The tapes sometimes got jammed inside the cartridge, or they’d stretch, rendering the data useless. Plus they cost about eight quid each, a lot of money in those days.

The Microdrive was the first strong indication that, perhaps, not everything Sinclair invented was going to be brilliant…

The Spectrum was followed up in 1984 by the Sinclair QL. It was aimed at the small business market and it missed its target by about half a light-year. Mostly this was because even though floppy drives were now readily available and getting cheaper all the time, the guys at Sinclair figured, “Hey, we spent a fortune inventing these Microdrives – let’s not let all that effort and money go to waste. Let’s build a couple into each QL! Yeah! Screw the industry standards – people’ll buy our stuff because we’re friggin’ GODS!” (I’m paraphrasing here, of course).

But even with the dreaded rattly little Microdrives built in, the QL might have been successful if Sinclair had made it compatible with the Spectrum. Not doing so was a huge, huge mistake. If it had been possible to run Spectrum programs on the QL, they’d have sold a hundred times as many units. Heck, if it had been even possible to convert Speccy programs for the QL, that would have been something (OK, it was possible, but not easy: completely different processors, operating systems and architecture meant that every program would have had to be redesigned from scratch – which wasn’t worth the trouble considering how few QLs had been sold).

And then came the Sinclair C5. You don’t want to know. Really, you don’t. Trust me.

Over time, Sinclair released other Spectrum models. The Spectrum+ came first. Internally it was identical to the 48KB model, but it had a new case with a slightly better keyboard. This was not overly popular with us established users because the new case meant that lots of the existing peripherals would no longer fit. Then came the 128KB model, which (Sinclair having learned from the QL debacle) was backwards-compatible with the 48KB model, and featured a few rather nice new enhancements.

Then Sinclair went bust, was taken over by Amstrad, and we were treated to a succession of new Spectrums: the +2, +2A, +2B and the +3. Not many people cared by that stage, because we’d all moved on to bigger machines like PC-compatibles, Amigas, or the Atari 520ST.

The golden years of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum were over, but those of us who were there, on the front-lines, spending night after night burning the midnight oil at both ends as we attempted to develop complex programming algorithms that would explain why we didn’t have social lives, those years were memorable.

So, yes, if you’re looking at the Speccy and thinking about how astonishingly primitive it is, you’re right. It’s primitive now. But it wasn’t primitive back then.

I bought mine in mid-1983, taught myself to program it, and a couple of years later was a proficient enough programmer to leave my job in the post office and move into the computer industry, where I remained for almost fourteen years and earned a heck of a lot of money. Which is not a bad return on a £99 investment.

(2018 should, if all goes well, see the release of the ZX Spectrum Next, an allegedly 100%-compatible computer that boasts a whole heap of up-to-date enhancements. I’m looking forward to that one... I might even dig out my old source code and finally finish that game I started working on in 1983.)

I enjoyed every bit of this article.And those early Sinclairs sell really well on auction! I have sold quite a few of those models, as well as games and accessories. As a young girl, I loved Atic Atac!!! But Manic Miner was my favourite. Thanks to you I have spent 20 minutes on YouTube watching those games.....!!!

You're welcome, onetree! Yes, Atic Atac was amazing: I loved that each of the three characters had different secret passages and different weapons - that gave the game so much more scope!

Beautiful article. Thank you very much for this moment of nostalgia.

Yes, I own a ZX Spectrum 48K. My first real programs were written in BASIC, pascal and assembler on Spectrum.

I remember I had to compile my longer Pascal programs from a cassette :)

I wrote my first computer game in Spectrum BASIC.

My best program so far was 800 bytes long. A ZX80 disassembler including command line interface and several really nice features :)

Yes, I was counting cycles and optimizing code all the time.

I was dreaming machine code.

Thanks again for this tear of beautiful memory in my eye!

I remember not being able to get to grips with Pascal at all: it completely baffled me! A few years later I got Turbo Pascal for the PC and it all clicked into place, but the Spectrum one defeated me. :(

I never wrote anything as sophisticated as a disassembler, but I did write a large, multi-function drawing program that piece-by-piece I gradually converted to machine code. Ah, that was fun!

I introduced Turbo Pascal to Optimal Software where I worked at the time (can't remember if that was before you joined up). Before that we were using a really crappy version of basic on the Husky Hunters. So did you discover Turbo Pascal before or after you joined O.S.?

After - I'd never even used a PC before I joined Optimal! I remember you teaching me the fundamentals of Pascal: before that, I'd never been able to grasp it - so I have you to thank!