How to Calculate your Basis in Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies

So it’s finally time. You got that last-long awaited W-2 and have compiled all of your crypto transactions into one gigantic spreadsheet, and it is time to follow that time-honored tradition of reporting your earnings and paying your taxes because we all like roads, parks, and military superiority, right?

The challenge of filing your return boils down to this: When is a gain reportable and what is the basis?

Depending on whether you are a day trader or a HODLer like me, the difficulty in making those determinations can vary widely.

Well, fear not because, as the title indicates, I am going to show you how to figure out what the heck you gained and what the heck you owe.

I considered adding a subtitle: “Why, oh why, did I choose to day trade? LIFO, FIFO, Long-Term, Short-Term - I’ll never figure all this mess this out. Oh, Roger Ver! Will you please hurry up and establish your Libertarian country so I can move there and be free of all this tax chaos?”

But then I realized I don’t want to live in such close proximity to Roger Ver, even if he did tone down his use of Bitcoin’s twitter account to pump Bitcoin Cash.

So let me start with an example to easily help you determine when you have a taxable gain. The accounting language we use is if the gain has been realized or remains unrealized, and it is actually quite simple.

If you bought a bitcoin in 2017 for $2,000 and still have it today, it is worth, $20,000, oh - $14,000, crap! - $8,900, relief - $10,500. Good grief, the market is volatile right now. For the sake of this example, let’s just say $10,000. Your Bitcoin being at $10,000 today is a true gain of $8,000 but because you haven’t “realized” that gain by selling your Bitcoin, you have not triggered a taxable event. Therefore, you have an unrealized gain and nothing to report to the IRS so life is good. On paper, you are $8,000 richer, but the IRS can’t charge you for that.

On the other hand, if you sold your Bitcoin for $10,000 on or before December 31, 2017, after buying it for $2,000 earlier in 2017, you have “realized” that gain of $8,000 and triggered a taxable event - specifically, a short-term capital gain. If you held it for longer than a year, it is a long-term gain. I won’t expand on that here since I have covered long-term and short-term gains sufficiently in What is The Cryptocurrency Tax Fairness Act of 2017 and how could it affect my Bitcoin transactions?

Now, we have been doing a little basic math here. $10,000 - $2,000 = $8,000. In that equation, the $10,000 represents the Fair Market Value, the $8,000 represents the gain and the $2,000 represents your basis, or cost. It really is just about that simple. Basis means cost. Or, more specifically, all costs incurred in the acquisition of the asset. That means you can add to your basis any fees or other charges associated with the acquisition.

For example, let’s say you used Coinbase to make your crypto purchase and paid a fee of $30 to buy that $2,000 of Bitcoin.

Side note -> Before I continue, I know someone is skipping to the end already to comment to me that I’d be an idiot to use Coinbase to buy anything when I can transfer everything for free to GDAX and pay no fees on a limit order. I can assure you, I and the 60,000 Youtube content creators claiming to have just “discovered” this tip on their own are aware of this. This is just an example to show how to treat a fee. Now go delete your comment and chill out.

So you paid a $30 fee to acquire that $2,000 Bitcoin. Because the fee was a cost of acquiring the Bitcoin, you add it to your basis which becomes, in fact, $2,030. That means your gain is actually only $7,970.00.

You can also deduct the cost of any fees associated with selling your Bitcoin so if it cost you another $30 to sell it, then you would report that as a deductible fee against the gain and reduce the capital gain to $7,940.00.

That, in a nutshell, is how you calculate your basis, your realized gain, and what you report to the IRS.

Like all things associated with the IRS, however, things tend to be much more complex.

For example, let’s assume you don’t have $2,000 to drop on Bitcoin at any given time so you have purchased $200 in Bitcoin per week since October effectively dollar cost averaging your purchase.

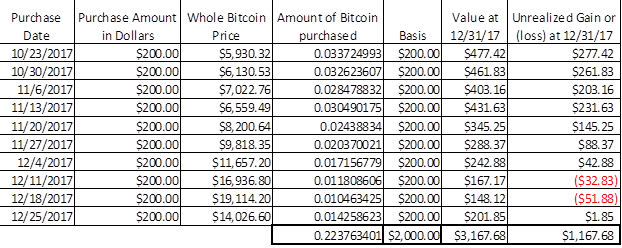

Using real, historical prices now, that means that, roughly, you made the following purchases.

Following that methodology, on December 31, 2017, you own just over 0.22 Bitcoin with an overall basis of $2,000. On December 31, the price of Bitcoin closed at $14,156.40, so the value of your investment at 12/31/17 is $3,167.68, giving you an unrealized gain of $1,167.68. Not bad. Would have been a lot better if you could have picked up a whole Bitcoin at $2,000 back in July but you missed the early train same as me. Talk about a validation for FOMO.

Now, the fun part. Let’s pretend that on December 31st, you needed to sell some Bitcoin to cover the cost of the new mining rig Santa brought you. So how do you account for which Satoshis you sold and what your basis was in those specific trades?

First, I need to make a correction. See two paragraphs ago where I said you have an overall basis of $2,000? Well, smack my hand because you can’t think of an “overall basis” in terms of your taxable gains and losses. You have to identify each transaction individually to determine the basis and subsequent realized gain or loss on what you sell.

Two common methods of identification are First-In-First-Out (FIFO) and Last-In-First-Out (LIFO). They mean exactly what they say. FIFO means you sell the oldest (or “first in”) asset in your holdings. LIFO means you sell the most recently purchased (or “last in”).

Generally speaking, in times of rising prices, it is most tax beneficial to utilize LIFO.

Think about that. Prices generally rose from October to December. Would you rather sell your First-In Bitcoin purchased October 23rd, realizing a gain of $277.42, or would you rather sell the Last-In Bitcoin purchased on December 25th and realize a gain of $1.85? I’d much rather pay tax on $1.85 than $277.

Likewise, in times of falling prices, it is frequently more tax beneficial to utilize FIFO which will create the bigger loss. Of course, you can only take the capital loss to offset against existing capital gains but you can carry the loss forward into future tax years if you can’t use it all in this year. This is the part where I again remind you to read my previous columns and, more importantly, consult with your tax professional.

Also, you should know that the default assumption by the IRS is that you are selling everything FIFO - of course, because that most often creates the largest gain and the biggest tax revenue for them. The burden is on you to document if you use a method other than FIFO and ensure that you track everything very carefully.

Another method I haven’t mentioned yet is Specific Identification. This is more challenging in that it requires a more detailed level of tracking but it can be the most beneficial because you can take advantage of the benefits of both LIFO and FIFO, depending upon the current environment, by handpicking which portions of your Bitcoin you will sell specifically.

So, for example, let’s say you need about $800 to cover that mining rig. You could sell the Bitcoin acquired on November 27th, and December 11th, 18th, and 25th, but not that purchased on December 4th. That would put $805.51 in your pocket and result in a realized net capital gain of only $5.51, and you are not left with any Loss Carryforward like you would be by selecting December 4th instead of November 27th.

I feel like I need to touch again briefly on a topic I have addressed more specifically in Will we finally get some relief from taxes on our Crypto? (U.S. Tax Code). That is trading cryptocurrency for cryptocurrency. If you exchange Bitcoin for Stellar Lumens for example, you are deemed to have sold your Bitcoin for fiat currency at its market price at that moment and purchased Stellar Lumens for their value in Fiat currency at that moment as well. Although we all know it is a trade, it is deemed to be a separated sale and subsequent purchase thereby creating a taxable gain or loss on the Bitcoin and establishing a new basis for the Stellar Lumens.

Yep, this stuff is complex. And, honestly, even though you are smart enough to figure out investing in crypto, you cannot get what you need to prepare a tax return from a column like this. What you can get from a blog like mine is a strong general knowledge that enables you to speak the same language, ask the right questions, and compile and provide the necessary data when meeting with your personal tax professional.

Even if they are new to the crypto space, they have spent a ton of time educating themselves on how to best handle every single scenario they might face and how to thoroughly research new ones like crypto. And since the tax code has sweeping changes for 2018, they get to do all the research and study again to figure out what best suits your tax situation next year. But the bottom line is, doing your part by reading columns like this saves your tax professional from spending time educating you on the basics, and saving their time means you get to keep more of your crypto gains for yourself.

As usual, feel free to subscribe for future updates, and when your tax professional marvels at your foundational knowledge and intellect, please consider making a small donation so my wife will quit griping about how much time I waste “goofing around with crypto.” Support The Crypto Tax Center

© Michael L. Collins

Congratulations @unimp-topics! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Congratulations @unimp-topics! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!