Working with Bitcoin HD wallets: Key derivation

This post was originally published on my blog.

If you are using Bitcoin regularly, you may have noticed that modern wallets let you

create multiple accounts with the same recovery seed and they create a new address

each time you create a payment request. This is important for privacy reasons

(if you were reusing the same address, your balance and your transaction

history would be publicly visible on the blockchain).

Key derivation has much more exciting applications though. You can have a cold

wallet stored securely, and you derive all your hot wallets from it. If a hot wallet

is compromised or lost, the rest of your wallets stay safe, and you can restore the funds

from the lost wallet using the cold wallet. Or imagine a large organisation, where

there is a top-level wallet managed by the CFO, and each department have there budgets

on their sub-wallets, having budget sub-wallets for different spending categories, and so on.

Public-key cryptography

As you might already know, Bitcoin is based on public-key, AKA asymmetric cryptography.

Every Bitcoin address is based on a public key. Knowing an address lets you send

transactions to that address, and see every transaction involving that address

(giving you the "balance").

What you cannot do, is to create new transactions from that address. You need the

private key for that. The public key can be generated from the private key, but not

the other way around. The private key should always stay secret, as it allows the owner

to spend the money from a given address.

The private key is a long sequence, not meant for human consumption. To store a private

key it can be encoded to a QR code and printed. Alternatively it can be deterministically

generated from a random seed, which can be represented by a set of natural language words

(mnemonics). These words are picked from a 2048-word list, defined by the BIP39 standard.

BIP39 seeds can optionally be salted with a passphrase. Both QR codes and mnemonics are relatively

resilient, making them suitable for long-term storage.

Child key derivation (CKD)

To have a lot of addresses and to be able to spend the funds arriving to those,

we need to keep track of the private key for each address. This is how old

wallets work: they generate new keys in batches, so the users have to make

regular backups of their wallets, to keep their set of keys up to date. If the wallet

is lost and the backup is not up to date, funds received by the new addresses

which are not backed up are lost forever.

Using key derivation, this is no longer necessary: with a predefined algorithm,

one can generate child keys based on a master key, use those child keys as master

keys to generate new children, and so on. Bitcoin's algorithm of choice is defined

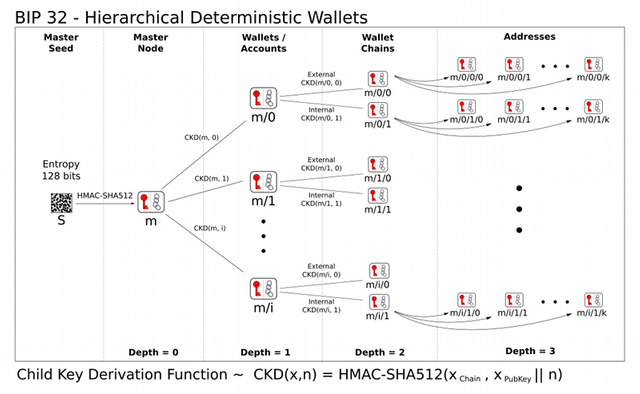

in the BIP32 standard.

The BIP32 CKD function has three parameters: The key itself, a so-called "chain code"

and an index. The combination of the key and the chain code is called an extended key.

The index is a 32-bit integer, allowing us to derive 232 child keys.

In case you were wondering, that's a lot of child keys.

HD wallets

As I mentioned already, a child key is also an extended key, so we can use it to generate

more child keys. That gives us a tree of keys - hence the name

hierarchical deterministic wallet (HD wallet for short). The list of indexes

used in each step gives us the derivation path of a key, like m/1/2/3, where m

denotes the initial key (AKA the master key).

Since there are endless possible variations of these paths, the BIP44 standard

specifies a limited set to use in HD wallets. If a user imports their private key to a

wallet application that implements BIP44 (such as Mycelium), it will automatically

keep generating addresses for the first account (m/44'/0'/0'/*/*), as long as it

finds transactions for them. If you add a second account, it will do the same.

To be continued! In the next part, we'll discover the mysteries of hardened derivation paths

and the use of extended public keys.