The BBC is wrong to broadcast Enoch Powell’s speech – it’s not a historical artefact, it’s a living tradition

I’ve always been drawn to the Odyssean qualities of nostalgia; the union in Homeric Greek of “homecoming” and “pain”. And as BBC Radio 4 prepares to broadcast Enoch Powell’s infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech (voiced by an actor) for the first time in its entirety this weekend as part of its Archive on 4 programme, I’m struck by the sense that nostalgia – the agony and impossibility of returning home – is the right word to describe not only the BBC’s approach to programming, but the ongoing state of mourning and melancholia in Britain’s postcolonial condition.

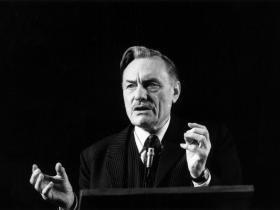

This April marks the 50th anniversary of Powell’s address to the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre, notionally to speak against the Labour government’s introduction of the Race Relations Act 1968. The remit of the legislation was to establish the Community Relations Commission and to outlaw discrimination on the grounds of race in the delivery of public services, housing and employment. However, the then Conservative shadow defence secretary used the speech to rail against what he called the “preventable evil” of migration from Commonwealth nations to the United Kingdom. In his words, the flow of people from those parts of the world that Britain had formerly colonised to the post-imperial motherland was “like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre”.

Enoch Powell, with his background in poetry and classics, painted a vivid picture of demographic catastrophe. It’s the allusion to Virgil’s Aeneid that most people remember: “As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood’.” But Powell’s most cunning rhetorical trick was to offer himself as a mere vessel for the vox populi. His most direct appeals to racist paranoia are purported quotations from his Wolverhampton South West constituents, including the famous prophecy that “in this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man” (an ordinary observation from an ordinary man, apparently “after a sentence or two about the weather”).

READ MORE

Fury as BBC says it will air Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers Of Blood’ speech

The wisdom of the crowd indeed. As Powell was roundly condemned by The Sunday Times for his “evil” “racialist” speech and sacked from the opposition front benches, he had no shortage of voices from below springing to his defence. A Gallup poll in 1968 found that 74 per cent of respondents agreed with the speech’s sentiments; 1,000 dockers from east London and 400 meat porters from Smithfield marched to protest the “victimisation” of Powell.

George L Bernstein has suggested that this outpouring of working-class support was because the MP had effectively conveyed the sense that he “was the first British politician who was actually listening to [the British people].” However, it is key to note that such mobilisations were covertly facilitated by fascist activists such as Dennis Harmston and the extreme right-wing group Moral Rearmament. The formal organisation of the far-right is often forgotten in even critical analyses of the speech’s social effects – our political culture chooses to remember these street actions as organic outbursts of grassroots populism.

Discontinued: 15 cars and trucks that automakers are dropping in 2018

USA Today

Trump og Kim møtes trolig i Singapore eller Mongolia

Bergens Tidende

Google’s CEO Could Be $380 Million Richer By the End of the Week

Time

by Taboola Sponsored Links

Stuart Hall, in his forensic analysis of authoritarian populism The Great Moving Right Show, argued that while “Mr Powell lost… Powellism won”. Margaret Thatcher (who had advised Edward Heath against sacking Powell after the speech) characterised her premiership with a hard tack to the right on matters of immigration, race and belonging. But the afterlife of Enoch Powell’s speech is more pervasive than the simple achievement of legislative goals. As Stuart Hall puts it, “Rivers of Blood” deftly wove “magical connections and short-circuits... between the themes of race and immigration control and the images of the nation, the British people and the destruction of ‘our culture, our way of life’.” And these images have been embedded in the national unconscious ever since.

Like one of Freud’s neurotics, British politics is racked by the compulsion to repeat. We see the ghost of Enoch Powell in Margaret Thatcher’s warning that the country would be “swamped” by Commonwealth migration and shades of Powellism in New Labour’s obsession with the asylum issue during Blair’s second term. Rachel Reeves’ prediction of race riots sweeping the “tinderbox” streets of Leeds has shades of the “throwing a match on to gunpowder” flourish in “Rivers of Blood”. And Nigel Farage’s “Breaking Point” posters are nothing but Funeral Pyre 2.0.

While the speech’s semicentennial will no doubt be marked by politicians of all stripes lining up to disavow Powell’s words, his rhetoric of racialised anxiety and demographic apocalypse continues to permeate every level of our culture, across the political spectrum. The steady rise of anti-immigrant xenophobia is perhaps testament to the idea that our parliament, with a handful of outliers, is stocked to the rafters with pound-shop Powells.

Why does such imagery continue to exert such a powerful force in politics? We must return to Enoch Powell’s speech for the answer – and in all that classicist bombast, listen closely for that which is unsaid. Powell took great care to stress that there is “nothing is more misleading than comparison between the Commonwealth immigrant in Britain and the American Negro” as the black population in the United States had been there “before the United States became a nation.” Commonwealth migrants are, by contrast, alien interlopers. The reasons for a person or a family wanting to travel halfway across the world remain strangely opaque; despite the Greco-Roman inflections to Enoch Powell’s oratory, the words “imperialism” and “empire” do not make an appearance once in the speech.

Here we see the double-voicedness of nostalgia. First, as the impossible longing for Britain as it never was – a homogeneously white sovereign entity, geographically and socially contained to a drizzly archipelago in the North Sea. And secondly, as the pain of homecoming – the trauma of immigration not as invasion, but of prodigal children returning. As Stuart Hall wrote of postwar, postcolonial migration: “We have been there for centuries. I was coming home. I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am the sweet tooth, the sugar plantations that rotted generations of English children’s teeth… That is the outside history that is inside the history of the English.”

The absence of empire in “Rivers of Blood” evades the troubling question that Britain, still smarting from the recent loss of its colonies, might owe a debt to its former subjects. Perhaps to take this idea of pain of homecoming further, we might understand migration not only as reparations, but as a reckoning. From Enoch Powell’s time to the present day, the existence of people of colour in this country is a constant reminder of Britain’s deepest trauma: in the words of Kerem Nisancioglu and Kojo Koram, that “through decolonisation… [Britain had] its arse handed to it by peoples it had imagined to be racially inferior”.

Political nostalgia is not the stuff of soft pastel shades or childhood summer days. It is a wound that refuses to heal over. It is the constant threat of invasion, not from migrants, but of our actual history puncturing the fiction of our idealised past. “Rivers of Blood” should not be memorialised like an artefact. Its rhetoric is a living tradition which shapes Britain to this very day. This is the pain of homecoming: the realisation that we are all the children of Enoch Powell.