Why Your Opinions of Universal Basic Income Don’t Matter

The world’s needs are being met with fewer and fewer workers. In the coming decades, the rapid rise of automation will permanently remove a growing number of people from the workforce necessary to support the global economy.

In short, most people will no longer need to work for us to maintain or grow our standards of living and quality of life.

Without work, an inevitable identity crisis will develop for millions of Americans, and billions worldwide. We covered those concerns in The Future of Work (and Your Identity). But what about the economic and social ramifications? What policies will become necessary to support this inevitable future?

The most serious proposal is also the most realistic: universal basic income.

It may not seem wise to immediately disregard the views of readers, but before discussing universal basic income itself, it’s important to know why your opinions (or mine) will have little impact on what policy measures are necessary to keep society running.

The basic premise of universal basic income—guaranteed, unconditional income for every citizen—is anathema to many. How do we motivate work and production if everyone’s needs are met? The short answer is: we won’t have to.

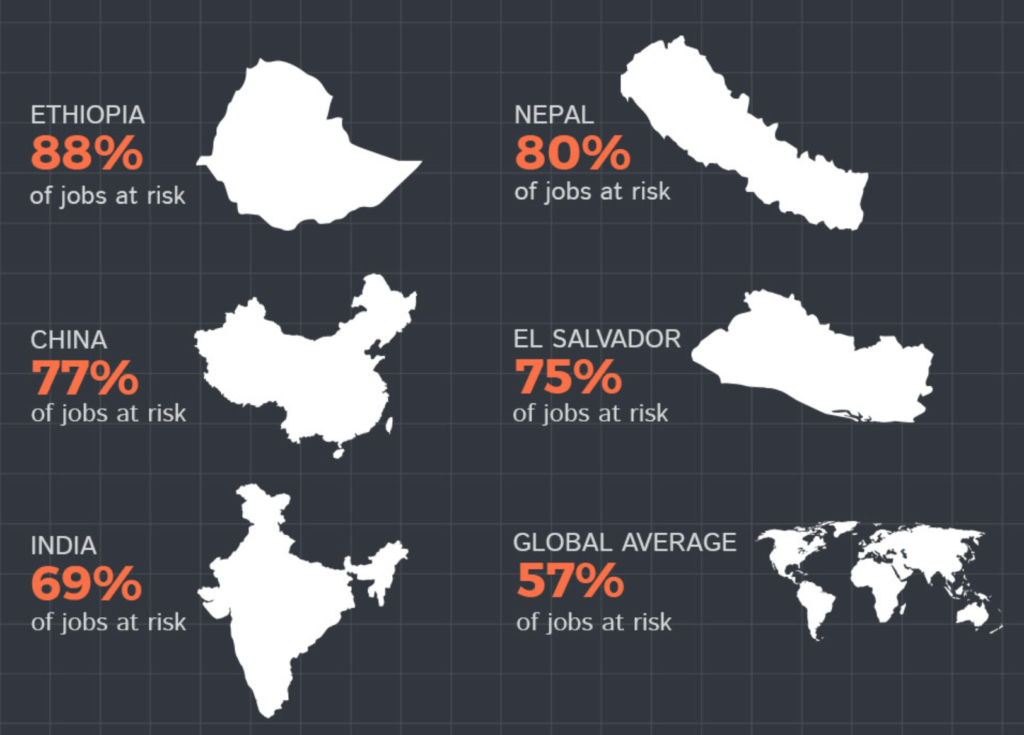

According to Citigroup, an investment bank, over half of global jobs will be eliminated due to automation based on current technologies alone. And these won’t be layoffs due to financial constraint; after these workers are eliminated from the workforce, the global economy will continue to produce as it did before.

Many countries will see nearly its entire human workforce rendered superfluous. China, which has over one-fifth of the world’s population, will see a 77 percent reduction in jobs. In the U.S., the University of Oxford estimates that future job eliminations due to automation range from 38 percent in Boston to 54 percent in Fresno.

Again, these estimates are based on current technologies. As robotic hardware and automation software improve over time, total job eliminations will likely be much higher.

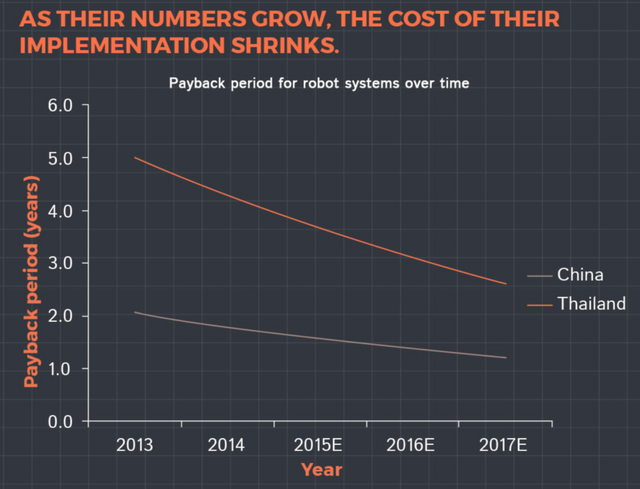

It’s also important to note that this change will be experienced with exponential speed. In 2013, it took the average Chinese business five years to recoup the cost of an industrial robot (mostly through wage savings by reducing employee headcount). Today, it takes less than three years for an industrial robot to pay for itself.

As the industry continues to scale, costs will fall further. Through 2019, the International Federation of Roboticspredicts the number of industrial robots to experience “continued growth averaging at least 13 percent per year.”

Falling costs incentivize businesses to install robot systems. And as more robot systems are installed, prices fall even further due to economies of scale, creating a self-reinforcing system. This momentum will persist for decades to come, as long as there are human wages to cut or eliminate.

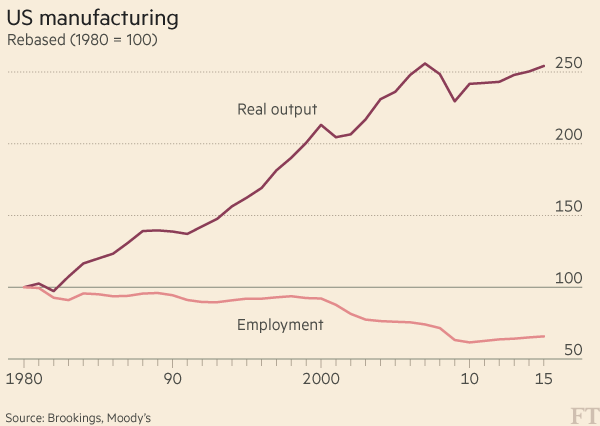

We’re already seeing automation permanently dislocate millions of people. Between 2000 and 2010, the U.S. lost roughly 5.6 million manufacturing jobs—a 30 percent decline. Manufacturing output, meanwhile, rose nearly 20 percent. This inverse relationship has existed for decades.

The Center for Business and Economic Research estimates that 85 percent of U.S. manufacturing job losses are attributable to technological change (automation). Businesses simply don’t need to hire anymore to grow.

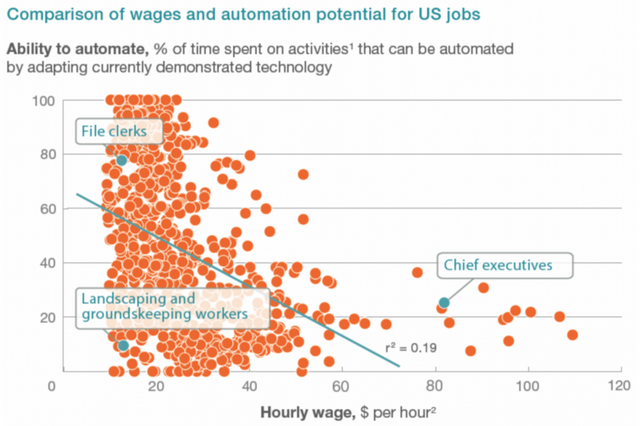

And these shifts aren’t just relegated to blue-collar jobs in the manufacturing sector. It’s easy to see how an assembly-line worker will be replaced by a robot. But what about a doctor? How will a robot completely replace your family physician? To put thousands of doctors out of the job, it won’t have to.

The biggest factor driving automation isn’t the complete replacement of jobs, but the elimination of certain processes. If you can automate 20 percent of a doctor’s tasks, you can effectively eliminate 20 percent of doctors without reducing the quality of care.

McKinsey & Company explains how automation will impact even the highest-paying jobs:

Our work to date suggests that a significant percentage of the activities performed by even those in the highest-paid occupations (for example, financial planners, physicians, and senior executives) can be automated by adapting current technology. For example, we estimate that activities consuming more than 20 percent of a CEO’s working time could be automated using current technologies. These include analyzing reports and data to inform operational decisions, preparing staff assignments, and reviewing status reports.

While jobs involving routine tasks will see the biggest declines—97 percent of fast food jobs are at risk—nearly everyone will see automation radicalize their industry of work.

Keep in mind that the numbers discussed here are huge. If the estimates of academics, investment banks, and global consulting firms are even close to correct, hundreds of millions (potentially billions) of humans will no longer need to work for the global economy to maintain production. With robots doing a significant amount of the work, we will all still enjoy the same material goods and services that we do today.

But who will be consuming these goods and services? And with what funds? In most Western economies, earnings have been tied to work. Without work, it would be tough for the average person to accrue enough wealth to participate in the formalized economy in any meaningful way.

That’s the primary issue of this paradigm shift: what will we do with the majority of people who will have no way to earn money or support themselves?

If you don’t think this will be a problem for you—perhaps you’re confident in your ability or willingness to continue working—think again.

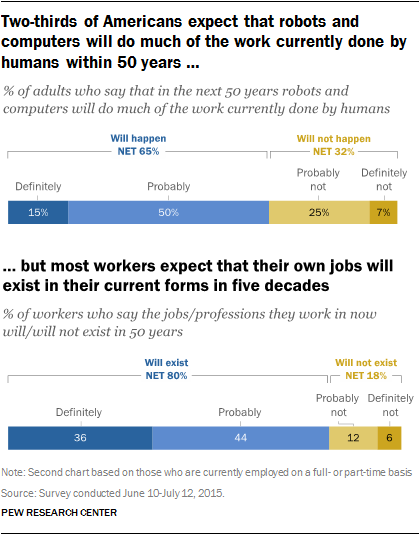

According to Pew Research Center, 65 percent of Americans agree that robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans within 50 years. So, most Americans agree that robots are coming. But should they worry about themselves? Incredibly, when asked what that meant for them, 80 percent of workers somehow expected that their own jobs will still exist in their current form in 50 years.

It’s time we admit to ourselves that the future global economy won’t need most workers to operate. More importantly, it likely won’t need you or me.

So what do we do about this? Our best option, in one form or another, is Universal Basic Income.