Basquiat: The Long-Awaited Party That Cost Him His Life

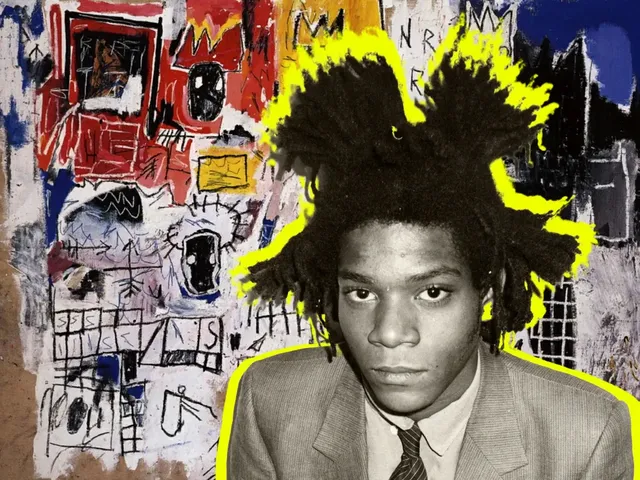

The Crown on His Head and Graffiti on the Walls

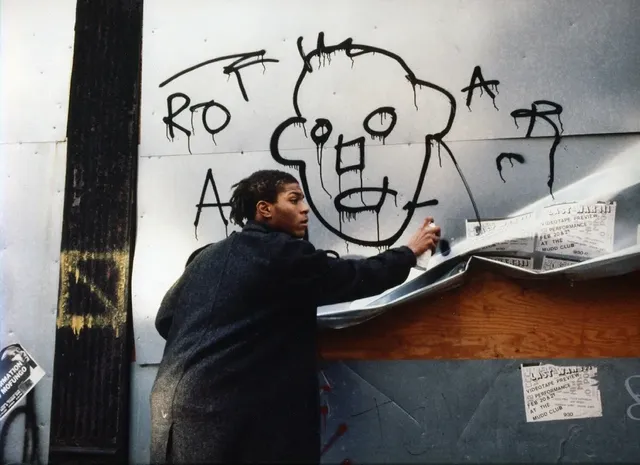

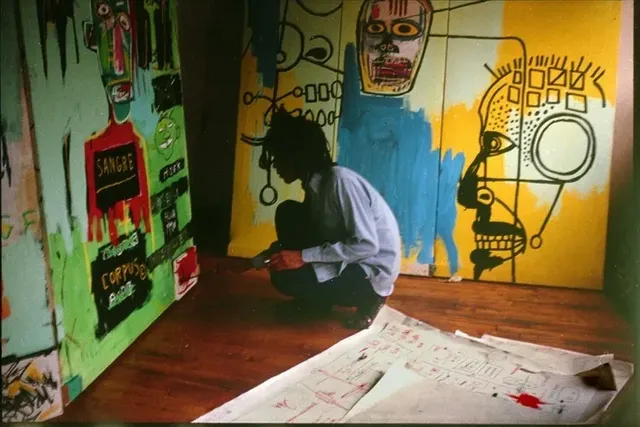

1980s New York resembled a spontaneous art performance: gritty, loud, and bursting with the vibrant colors of graffiti and the glow of neon signs. It was here, in the concrete jungle where everyone fought to shout their name into the crowd, that a teenager appeared with the idea that he was a king. Not as a joke, but in full seriousness — Jean-Michel Basquiat tagged walls with “SAMO” and sketched crowns.

The roots of his confidence lay in a childhood that was both brilliant and tragic. His parents — a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother — instilled in him a love of culture and languages. Jean-Michel spoke English, Spanish, and French, read books before he even started school, and could quote medical manuals (this is how he first learned about anatomy, which later became a key element in his art). But the fairy tale ended early: at seven, he was hit by a car and spent a month in the hospital. It was during this time that his mother gave him an anatomy atlas — a book he would never forget.

His mother, an artist herself, was the first to believe in his talent. However, she began to suffer from mental health issues, and Jean-Michel was left in the care of his father, a cold and strict accountant. At 15, he ran away from home and began roaming the streets, creating his first works on the city walls.

His crown was a challenge. It was for those who didn’t believe in fairy tales about princes as children and for those who didn’t expect salvation from the system. The crown on a grimy Brooklyn wall became a symbol of a street renaissance, where art didn’t reach museums but lived amidst trash and the wails of sirens.

Critics wondered for a long time why this young man suddenly decided he was the new king of art. But Basquiat wasn’t asking anyone. He already knew: if you don’t claim the crown yourself, no one will hand it to you.

New York: Where There’s More Talent Than Jobs

1980s New York wasn’t just a city; it was a pack of the crazed and ambitious. Artists? They were everywhere, like autumn leaves blanketing the streets. Step into any café, and you’d find someone sketching with a pencil or hauling canvases on their back. Street galleries thrived where censorship was a nonexistent concept, and art was nothing more than a scream no gallerist could hear unless they made it through the night.

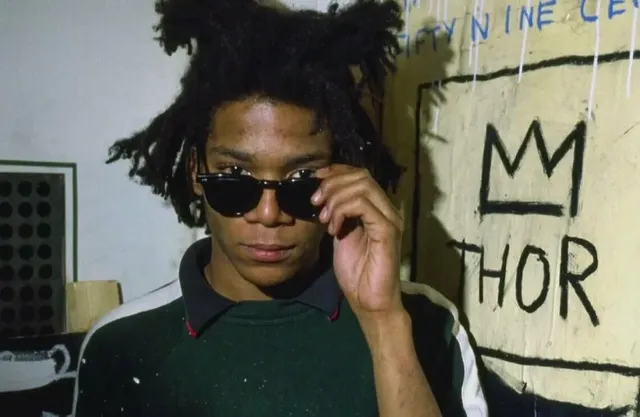

But Basquiat? He was a child of these streets. Elite exhibitions didn’t faze him; his canvas was the city, and his brush was a spray can, leaving marks wherever he went. “The most valuable thing I have to offer is my thoughts,” he said, and his works were direct punches to the face — an anti-glamorous response to the bourgeois gallery grind.

Here’s the paradox: in a city bursting with thousands of talents capable of moving mountains but destined to remain unknown, Basquiat broke through. Why? Because he was insane. And, damn it, that was cool. His paintings were pure chaos, devoid of any traditional aesthetics. In one of his most famous works, he wrote: “I never tried to be an artist. I just tried to depict what I saw.”

The problem wasn’t talent — New York had talent in spades. The challenge was being crazy enough for people to think, “He’s out of his mind, so he must be authentic.” Basquiat didn’t just create art; he created an epic. His works weren’t beautiful — they were raw, honest, and sometimes unbearably absurd. But every stroke screamed, “I’m here!” Impossible to ignore. You couldn’t miss him, and you couldn’t help but become a fan.

The other artists? Like addicts without a prescription. But Basquiat? He had no brakes. “I paint because I can’t not paint,” he said — and that was everything.

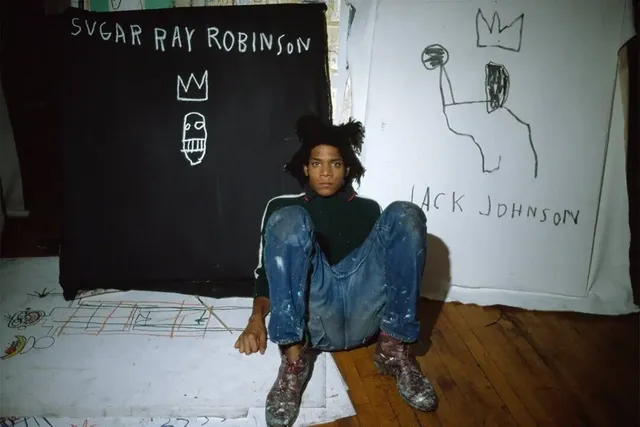

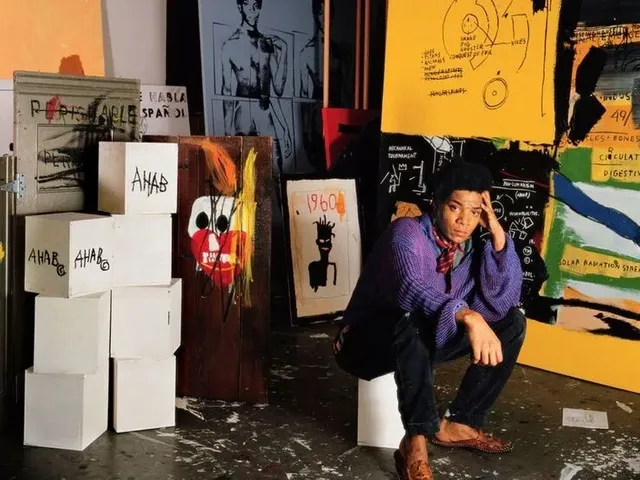

Skulls, Codes, and Kings: Decoding Basquiat

Basquiat didn’t paint for an audience; he painted for himself. Not to explain, but to encrypt. His works weren’t just paintings — they were like hard drives loaded with personal pain, ambition, and anger, difficult to decipher. He wasn’t trying to please anyone — not gallerists, not viewers, not even himself. He simply created worlds that absorbed everything: his emotions, the city, the country, and even the entirety of human history.

“Skulls mean death. And death, as we know, is the ultimate way to be free,” Basquiat explained his fascination with anatomy and skulls. In his works, they served as symbols — something like self-portraits, but devoid of pity or bitterness. Instead, they radiated a detached certainty that everything ends and begins with emptiness.

He wrote incessantly and everywhere. Anything he could find became his canvas. Yet within this chaos were delicate, seemingly accidental elements — intriguing codes and words that resisted immediate comprehension. It was as if every brushstroke was part of a cipher, and the painting itself a puzzle. One of the most notable aspects of his works was the interplay of text and imagery, where figures would randomly align with words, and these words became a kind of key: “The worst thing that can happen to you is not being understood.”

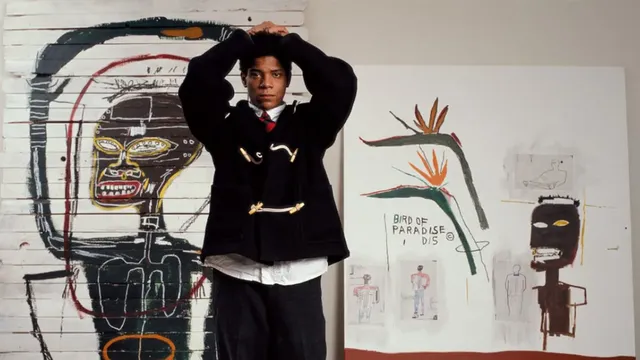

Basquiat painted kings, but he wasn’t one of them. He seemed to embody the crown without wearing it. His paintings lacked polish; they weren’t glamorous like Kate Moss on the cover of Vogue, nor did they aspire to be perfect. His crown symbolized torment and incredible strength. Every line was a blow, every stroke a reminder that no one is free from their roots, their past. He returned to crowns repeatedly because he felt like an outsider in the art world — a traitor to its traditions, claiming a place that wasn’t predestined but fought for.

His art wasn’t mere abstraction; it was his way of confronting reality — not by escaping it but by grabbing it by the throat. Basquiat was a master at decoding his own consciousness. And the harder we tried to understand him, the more complex his works became. But for him, it was simple: “I don’t paint anything I can’t say in words. I just say it with paint.”

Who Didn’t Sleep with Jean-Michel? Andy, Madonna, and Others

Basquiat could have been the star of any reality show, but fortunately, his life refused to follow a script. His relationships were more than just connections — they were eccentric, absurd, and sometimes as tragic as his entire journey in art.

Who didn’t cross paths with his gaze or feel the touch of his hand? Among the brightest figures was Andy Warhol, his mentor and possibly the only person in the world Basquiat saw as an equal. But theirs wasn’t the warmth usually attributed to mentor-student relationships. Warhol, the seasoned manipulator, kept Basquiat under his control, effectively turning him into a living experiment — how much could be extracted from a genius artist? Warhol pulled the strings, yet Basquiat continued to love him as a muse. Andy was both an inspiration and a trap. Basquiat often remarked, “He was too old to understand me, but too brilliant to let me go.”

Madonna? Oh, absolutely. They were together, but their relationship was more a game than anything serious. Basquiat could never be her ideal, and she wasn’t his. It was a clash of worlds: Madonna with her flamboyance and sugary glamour versus Basquiat’s chaos and sharp edges. At times, it seemed their relationship was a test of endurance, especially when Basquiat portrayed her in his work as an abstraction, reducing her image to a black square. It was his way of declaring, “You’re a star, but your shine doesn’t interest me.” Madonna called the piece a “joke” but could never forget the gesture. “He was the first to show me that glamour could be disarmed with a black square,” she later admitted.

But Basquiat wasn’t just a master of romantic manipulation; he was often the victim too. One of his significant connections was with artist Cathleen Cahill, a woman he lived with in Brooklyn during a turbulent period. Cathleen was more than a lover — she was an artist sharing his creative torment. Yet their relationship had a dark undercurrent. Basquiat introduced her to the world of drugs, and as his career skyrocketed, her envy deepened. Talented though she was, her success couldn’t match his. Eventually, Basquiat left her, leaving Cathleen to wonder why things fell apart. “He was my greatest inspiration and my worst nightmare. He broke me, but he didn’t stay,” she once reflected. Her jealousy of his achievements festered in her work, further solidifying the rift between them.

Jean-Michel could have been the subject of countless songs, books, and films, but his life wasn’t a cascade of romantic escapades. It was a chilling glimpse into what happens when genius collides with reality.

How to Sell Your Soul Without Even Noticing

Time — your greatest enemy. You think your art is pure and beautiful, a reflection of your untainted soul. But then capitalism barges in like an uninvited guest at a party, devouring all the hors d’oeuvres and walking off with your last glass of champagne. You don’t even notice how they’re wiping their feet on your soul. You keep laughing, signing contracts, because recognition feels so damn good. Yet with every contract, you become less of a person and more of a brand. Suddenly, you’re not selling paintings; you’re selling yourself. But did anyone even notice when you turned into a commodity? Not you — because status and money are what matter, right?

All those galleries, exhibitions, auctions — they’re not business, they’re art! Or so you told yourself. Did you actually believe your name was just the product of your talent, untouched by the system that turns everything into mass-market goods?

When your paintings start pulling in millions, and you’re still hanging out on the streets, bottle in hand and high as a kite, you’ve already crossed over. You’re no longer an artist — you’re capital. And there you are, on a pedestal, looking down at it all and thinking, “How the hell did I get here?” Recognition is like an expensive drug: intoxicating until it overdoses you. You revel in it, unaware that the high costs your freedom. Becoming a symbol? That’s just a new form of slavery. You’re no longer human — you’re a brand.

And then, in a drunken haze, psychedelics coursing through your veins, you see thugs hacking away at the walls where your graffiti once lived. You stumble toward them with a bottle in hand, thinking you’ll show them your genius. You’ll create something truly monumental. Instead of painting your name across their faces — “Basquiat’s Graffiti” — you get knocked down. Of course. Why not? You’re an artist, but why would anyone treat you like a regular person? Listening to artists isn’t necessary when you can simply punch them in the face. You didn’t even notice when you became part of this cruel spectacle where your work sells for millions at auctions while you… well, you’re just the walking ad for it.

On the outside, you’re a “genius.” On the inside? Hollow.

Gallery owners, managers, publicists — all those people who shake your hand with beaming smiles, saying, “You’re incredible!” — they’re just holding onto your leash. You’ll never notice how they’re already guiding you into a cage. Did you sell your soul? Oh no. You just didn’t notice when it happened. All those millions — they’re not yours. They belong to the system. And you? You’re just a cog in its wheel, spinning endlessly in search of recognition, only to realize too late that it’s become your prison.

The Genius Who Wasn’t Understood (Or Simply Ignored?)

Basquiat was a comet tearing through New York’s art scene, only to burn out, leaving nothing but ashes in his wake. The question remains: was he truly a misunderstood genius, or is that just a convenient excuse for those who embraced the system and chose to look away from the man and his art?

Here’s the reality: his work — a volatile cocktail of street poetry, primitive abstraction, and brutal symbolism — wasn’t misunderstood; it was too sharp for an audience accustomed to tidy labels and classical aesthetics. Like all “misunderstood geniuses,” Basquiat became a victim of the very world that exploited him. He wasn’t allowed sincerity — instead, he was priced, tagged, and sold as a product. His “genius” was reduced to auction fodder, where meaning was drowned out by the deafening roar of bidding wars.

Or maybe they just didn’t want to understand him. After all, who really wants to engage with an artist painting skulls, scrawling graffiti, and coding cryptic messages into his canvases? People preferred to see him as something convenient — something that could hang on a wall and be forgotten, like last season’s trend. Basquiat became the living embodiment of postmodernism: “I am not an artist, I am an event.” But his “event” didn’t fit neatly into the frameworks of art that someone needed to monetize.

So, what did he become? A genius who was misunderstood? Or just a convenient mask for a beautiful myth that could be exploited? It’s unclear. But one thing is certain: Basquiat’s genius lay in his raw sincerity, a quality too pure for a world incapable of digesting it. When his career became a machine turning art into commodity, he became his greatest fear — a picture on a wall, stripped of meaning, existing only for shallow consumption.

So, who didn’t understand him? Himself? Or the people who branded him, leaving him alone in a gallery of empty frames?

27 Years Old — The Perfect Age for Myths

“27 Years Old — The Perfect Age for Myths”

Ah, 27 — a number not just of years but an exclusive club, fleeting and enigmatic, leaving behind murky memories and a heap of amusing theories. Myths are born from this age. After all, who better to embody the duality of genius and tragedy, prophet and victim, the living spirit of art and its most pitiful echo, than a 27-year-old?

Basquiat left this world at that age — prime time for mythmaking. Because, as we all know, to become a legend, all you really need to do is die young. At 27, you transcend humanity to become a concept, a symbol of all you could have been but never lived to see. Facts don’t matter anymore — the myth overpowers reality.

Basquiat was a genius. But couldn’t one argue that he was just a victim of circumstance? A pawn in a cruel game? But who would want to believe that? We need heroes, and a hero who dies too soon is tailor-made for myth. Basquiat joined the ranks of other “27-year-olds,” where drugs, alcohol, and creative energy swirl into the perfect cocktail of mythologized tragedy.

This club is crowded with “greats.” Kurt Cobain, whose voice defined a generation, left us at 27 — forever a symbol of his time, despite being, in reality, just another flawed human like the rest of us. Jim Morrison, the 1960s idol with his eternal poetry and punk spirit, is another cornerstone of this legend. And Cobain? What’s his myth without that final Rolling Stone interview where he said, “I don’t want to be an idol anymore. I don’t want to make music for people who don’t understand me.”

“That hollow feeling — being famous but never connected to anyone,” Cobain lamented. Jim and Kurt — both joined this myth: young, brilliant, yet so misunderstood. They were perfect victims of their fame. Their deaths weren’t just personal tragedies; they became untouchable legends. Because a “genius” at 27 is simply too good for this world. Had they lived, the industry would have chewed them up and spit them out.

And then there’s Basquiat. “I’m not an artist; I’m a legend,” he declared, perhaps not knowing that at 27, he’d already be gone. At some point, death became part of his art. This age — 27 — became the perfect moment to seal his myth, one we now carry like gospel in our collective minds.

He Died, But He Didn’t Go Silent

Basquiat left at 27 — prime myth-making age — and immediately became a brand, almost as if he knew: if you don’t fully sell your soul while alive, you’ll at least get compensation posthumously through auctions. There’s much to say about his legacy, but let’s start with the numbers: his works today sell for millions, snapped up as eagerly as cheap drinks at a party — with the same greed and the belief that they’ll surely pay off. In 2024, one of his paintings sold for $110 million. Yes, $110 million. A skull rendered in brutal strokes, chaotic lines, and raw energy. The irony! We all adore chaos when it’s profitable.

And those collectors, sitting united with glasses in hand at auctions — they’re not art enthusiasts. They’re just people who’ve figured out how to make money from it.

Let’s talk about a few pieces that have become greed’s ultimate trophies, coveted by collectors:

“Untitled” (1981) — A skull, aggressive and alive, embodying the relentless energy of the artist. This piece sold for $110.5 million at Sotheby’s in 2017, setting a record for Basquiat.

Quote: “This work doesn’t just symbolize his art; it embodies how unique Basquiat was as an artist.” — Larry Gagosian, renowned gallerist.

“Untitled” (1982) — A vivid face, rendered in bold colors and ferocious strokes, sold for $57.3 million at Christie’s in 2016.

Quote: “This isn’t just a painting; it’s a cultural artifact, one that transcends us and our perception of the world.” — Adam Lindemann, collector.

“The Irony of Negro Policeman” (1981) — A bright, sinister work loaded with social critique, sold for $22.5 million.

Quote: “Basquiat managed to articulate everything that couldn’t be said in words. His art wasn’t just about colors; it was about meaning, embedded in every line.” — Toby Devan Lewis, collector.

Here’s the real kicker: while Basquiat was alive, none of these paintings fetched such astronomical sums. He didn’t know his imagery would become “investments.” Or perhaps he did, but was too exhausted to care.

Now, decades later, with him gone, we can all smirk at how his works have become such high-value commodities in the art market. But let’s not forget: when he was alive, they weren’t. And maybe he knew it. Or maybe he was too tired to think about it.

So yes, Basquiat died, but he didn’t go silent. Like many greats, he proved far more valuable to the world after death than during his life. His genius became the perfect fuel for myths, and those myths — the ideal currency for those skilled at profiting off the truth.

Who’s to blame? Everyone. All of us.