The Roving Bandit vs. The Stationary Bandit: A Justification for the Existence of a Nation-State

Ludwig von Mises explains that the problem with socialism is a lack of economic calculation. Without a pricing system there is no way to determine who should produce what, how much of it should be produced, and what is the most successful way to produce it. If one says that government should be limited to police, military, and courts, who determines how many policemen and courts there are, and how big the military should be? Who decides how much taxes are necessary to supply necessaries and what incentive is there for government to eliminate waste or even be aware of it if it is not possible for them to be put out of business by a competitor who is less wasteful?

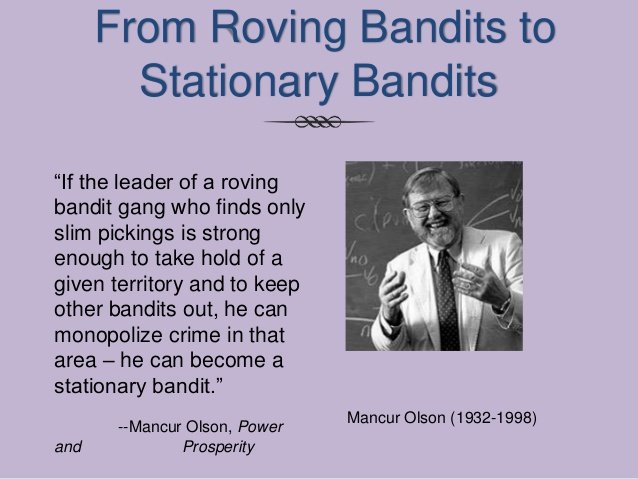

Holcombe argues that the government is not designed to provide goods and services but to redistribute wealth. The government is described as a stationary bandit that extracts income from people and in exchange removes the roving bandits who would be even more predatory (Holcombe 2004, 329). According to the stationary bandit model, law and order is a public good. Primitive societies where goods were held in common were able to protect themselves, but in agrarian, individualized societies where property was not held in common there was little incentive to produce public goods, such as law and order.

In a society of 1,000 people, a person only gets 1/1,000th of the protection from producing law and order, so it would not be worth it to produce the public good himself (Klitgaard & Tinggard 2003, 256). Since there would be no property protection, people were at the mercy of others who would rob and plunder them. A roving bandit, such as the Vikings from the 8th to the 11th century, would come along and rob a bunch of people in a village and then wander off. Since all of the gains would go to whoever was the strongest, it was worth it to engage in predation. In order to prevent such roving bandits from continually blundering people, the people would be willing to tolerate a stationary bandit instead.

The stationary bandit would tax people, often heavily, and enforce and protect property rights. A roving bandit has a high time preference since he does not care that his stealing reduces the incentives of the people he robs from to produce. On the other hand, a stationary bandit does not want to disincentivize the looted since he will also gain a share in the future produce the looted produces. A stationary bandit has an incentive to take property from someone, but not enough to discourage him from no longer producing. A stationary bandit also views roving bandits as competition and so has an incentive to prohibit roving bandits from pillaging his citizenry since that is his job.

A government is set up to act as a stationary bandit, which is less predatory than the roving bandit. A government prevents roving bandits from continually looting people and hence the people are better off under the stationary bandit than being under constant roving bandits that would take the whole produce instead of just a portion. According to Kintgaard and Tinngard, the state of medieval China has its origins as becoming a stationary bandit, which they say the people preferred (Klitgaard & Tinggard 2003, 256).

While Holcombe does not make the assumption that law and order is a public good the market won’t provide, he does make the claim that in the absence of the state the other alternative is to be at the mercy of an even worse predatory gang. The real choice is not between market or government provision of public goods but between a roving gang or a stationary gang. In the absence of a nation-state there would be a roving bandit who would be more predatory since he steals resources and moves along, without concern that doing so will cause his victims to produce less in the future. The government is like a shepherd who wants his animals to be nice and fat since they will sell more on the market that way. Having free-range humans allows humans to be more productive than they would be under constant expropriation and slavery.

The stationary bandit theory has an overly pessimistic view of anarchy and an overly optimistic view of government. The theory assumes it is in the self-interest of the bandit to loot people and that other people would be at his mercy. As Benson, Friedman, and others have pointed out, under societies that lacked a nation-state people would often join coalitions to come to their aid. Instead of one person defending himself against another, the coalition would come to help those who joined their group. The origins of Anglo-Saxton law had such a system.

Anglo-Saxton law can be traced back to Germanic customary law (Curott & Stringham 2010, 10). The Anglo-Saxtons came from Germanic tribes who invaded England during the 5th century and brought their Germanic customs with them. The Germanic customs has a legal code where people were part of tribes. Unlike a caste system, being in the tribes were voluntary. Each tribe consisted of a hundred men, called pagi (later to be known as “the hundred” in the 10th century), which was further divided into groups called vici who were responsible for policing (Curott & Stringham 2010, 10). The men who joined the tribes agreed to protect each other.

While such tribes came about through custom and kinship, such tribal arrangements were later adopted by the English common law system during the 10th century. The hundreds were also divided into other groups, sometimes as small as ten men in a system known as borh (Curott & Stringham 2010, 11). Since there was no standing army or nationalized police force, groups such as the hundred acted as a decentralized police force. People who decided to join the groups took what was known as a frankpledge, which was an oath where each group swore to both abide by the rules of the group and to protect the other members of the group when in need. In such a group, each member was responsible and looked out for the other members of the group. If one stole or committed other acts of aggression and failed to abide by the verdict he was declared an outlaw. In order to ensure cooperation and trust, many members of the tribes refused to engage in trade and exchange unless a person was a part of the surety system. If a person was unable to prove that he was a member of a coalition that could pledge on his behalf that conveyed a signal to people that such a person was untrustworthy and so had trouble joining another group for protection and engaging in trade and exchange (Liggio 1977, 273).

The Anglo-Saxon private legal system signaled trust to people by trading with them, intermarrying into other groups, giving gifts, and having people vouch on their behalf. One solution out of the Hobbesian jungle is not to have to fight a roving gang on one’s own but to join defense groups that would come to your aid, like what occurred in Anglo-Saxton England.

Ayn Rand has opined that having different policing groups enforce different laws within the same geographical area would lead to violent conflict when the different policing groups would interact with each other and disagree on who the guilty party is and what the law should be (Rand 1964, 117). Under the law of the marches and medieval Iceland peaceful resolutions were possible without government courts. There are today disputes between countries and disputes between people from different states. The solution to solve conflicts is not always an outbreak of violence, since such behavior is expensive and self-destructive.

[Except from my article, "Anarchy: The Lesser of Two Evils," which can be found here: https://works.bepress.com/daniel_rothschild/10/]