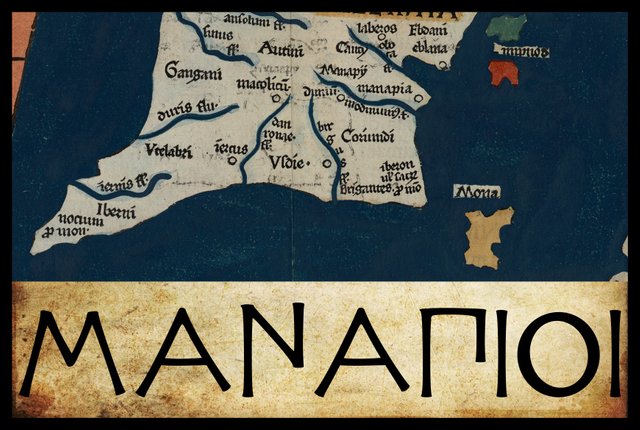

Μαναπιοι

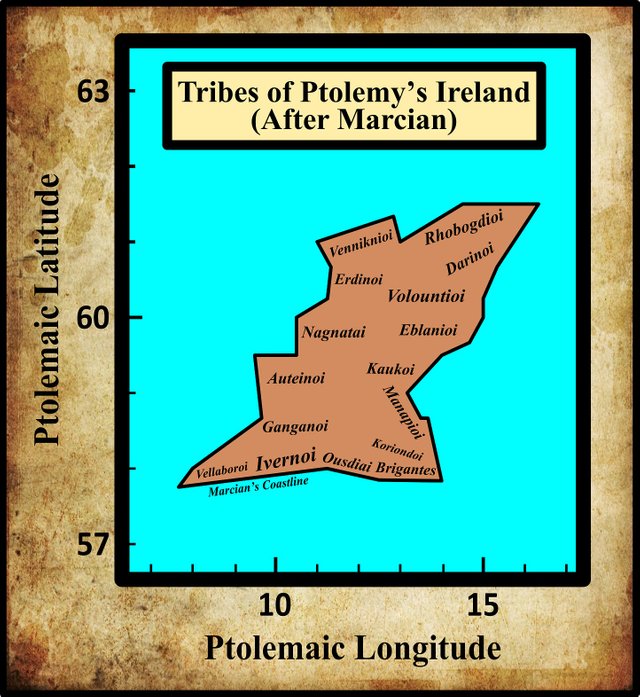

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen native tribes. Beginning, as before, in the southeast corner of the island and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction, the third of these are the Manapioi. These people are described as lying on the east coast, to the south of the Kaukoi and followed by the Koriondoi.

No variant readings of this ethnonym are noted by Karl Müller in his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, or by Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg in his 1838 edition.

Manapioi

That Ptolemy’s Irish Manapioi were related to the Gallic tribe known as the Menapioi (Latin: Menapii) has long been accepted by scholars. In his description of County Wexford, the British antiquary William Camden even referred to them by the same name:

... the County of Weisford or Wexford ... where the Menapii are plac’d by Ptolemy. That these Menapii were the offspring of the Menapii upon the Sea-coast of the Lower Germany, the name it self seems to intimate. But whether that Carausius who set up for Emperor in Britain against Dioclesian, as of this, or that Nation, I leave to the Enquiry of others. For Aurelius Victor calls him a Citizen of Menapia; and the City Menapia is plac’d by Geographers in Ireland, and not in the Low Countreys. (Camden 1359)

The Irish antiquary James Ware also misspelled the name of this people. Moreover, he stated:

MENAPII, a People: They inhabited the countries now called the Counties of Wexford and Waterford. (Ware & Harris 42)

He does not explain how he arrived at this conclusion. Ptolemy clearly places the Manapioi on the east coast, whereas County Waterford is on the south coast. Apparently this misplacement was due to the fact that several early scholars identified Manapia, the “capital city” of the Manapioi, with Waterford City.

In 1894, Goddard Orpen repeated much of what Camden had already claimed, but he also suggested a connection between the Manapioi and the Isle of Man:

The Manapii may have been an offshoot from the Menapii of Belgic Gaul, and professor Rhys has lately in this Journal [“Early Irish Conquests of Wales and Dumnonia”, Journal, R.S.A.I., 1890-1, pp. 651 et seq.] given some new grounds for thinking that Carausius, called “Menapiæ civis” by Eumenius, hailed from the Irish Menapia. The name Manapia may also be equated with one form of that of the Isle of Man, the form which has yielded the Welsh Manaw, and Pliny expressly calls the island Monapia ... there are many indications suggesting an early connection between Man and Ireland. Among these it must here suffice to allude to the common traditions concerning Manannan Mac Lir, to the fact that Ptolemy classes the island with Ireland; while Tigernach records that somewhat later, in A.D. 254, the Cruithne or Irish Picts, driven out from Ulster by Cormac Mac Art, fled to the Isle of Man; and in the fifth century Orosius (i. c. 2) speaks of it as aeque (with Hibernia) a Scotorum gentibus habitata [likewise inhabited by tribes of the Irish] (Orpen 124-125)

The Irish historian Eoin MacNeill also connected the name of Ptolemy’s Manapioi with that of the Gallic tribe known as the Menapioi:

North of the Brigantes, on the Leinster coast, Ptolemy locates the Manapii. It can hardly be doubted that these were a Belgic people, a branch of the Menapii, whose territory on the Continent lay in parts of the countries now called Belgium and Holland. [Footnote: The syllables en and an are found interchangeable in many Celtic words, perhaps varying according to dialect.] (MacNeill 57)

Noting that no trace of the Manapioi are to be found in this part of the country in our native records, he then speculates that their descendants may have survived as a tribe found in historical times in Ulster:

It seems to me possible that the Manapii may be represented in later times by a scattered people called the Monaigh or Manaigh. Some of these dwelt in eastern Ulster, near Belfast. Another branch of them dwelt in the west of Ulster, and their name is preserved in that of the county Fermanagh. It is interesting to note that the Irish genealogists derive the origin of both from Leinster. The only trace known to me in Irish tradition of a people similarly named on the south-eastern seaboard is found in the name of Forgall Monach, the father of Emer who was wife of Cu Chulainn. (MacNeill 58)

T F O’Rahilly concurs:

The name of the MANAPII has long been recognized as a variant of that of the Menapii, a Gaulish tribe who were seated on the Meuse and on the Lower Rhine. Mac Neill was the first to suggest that the people who in Irish documents are called Monaig or Manaig may be representatives of Ptolemy’s Manapii. Monaig, which seems to be the older form in Irish, would go back to *Monakvī and thence to *Monapī ... Early in the historical period we find Monaig or Manaig surviving in two communities, one situated in Uí Echach Ulad in the west of Co. Down, and the other in the neighbourhood of Lough Erne. [Footnote: Later the name of these was altered to Fir Manach, which became a district name (‘Fermanagh’) ...] According to the Tripartite Life, the Manaig of Uí Chremthain [Footnote: ... the Manaig of Lough Erne.] and of Ulaid are branches of the Uí Bairrche. With this the genealogists are in agreement, for they tell us that both sections of the Monaig descend, like the Uí Bairrche, from Fiacc, son of Dáire Barrach, son of Cathaer Már. Evidently the tradition of the Monaig was that they had come from South Leinster, the home of the Uí Bairrche, with whom they claimed kinship. (O’Rahilly 30-32)

O’Rahilly concludes:

The practical identity of their names authorizes us to believe that the Monaig were ultimately an offshoot of the Menapii, who were one of the group of tribes collectively known as Belgae. Hence we may infer that the Monaig were Builg or Fir Bolg (*Bolgī, variant of *Belgae). With this inference agrees the fact that ‘the seven communities of the Monaig’, dwelling ‘in the land of the Ulaid’, are classed among the Fir Bolg. Similarly the descent of the Monaig from Dáire Barrach implies that they were Érainn (=Builg). Like the Builg in general, we may assume that the Monaig reached Ireland via Britain, and not direct from the Continent. If the Menapii or Monapi are not attested in Britain, it is a likely conjecture that they had been neighbours of the Brigantes in Britain (much as they were in Ireland), and that they later became merged with them. (O’Rahilly 33)

That the Manapioi of Ireland were a Celtic Belgic tribe cannot be seriously doubted, and it seems likely that the historical Monaig of Ulster were their descendants.

Territory of the Manapioi

It might be thought that Ptolemy’s disposition of the tribes along the east coast of Ireland would leave little room for speculation concerning the territory of the Manapioi. But Ptolemy also assigned a “city” to this tribe: Manapia. It stands to reason that Manapia lay in the territory of the Manapia—and therein lies the rub. Those who would locate Manapia in the vicinity of the modern town of Wexford—I am one of these—must then explain how the Koriondoi could have dwelt between the Manapioi and the Brigantes. It would certainly be easier to push the Manapioi further north into County Wicklow, leaving plenty of room for both the Koriondoi and the Brigantes—but now the problem is to find a suitable candidate for Manapia.

In the preceding article in this series, I quoted Orpen on this quandary and I suggested one possible solution:

The Κοριονδοί [Koriondoi] are placed by Ptolemy above the Brigantes who, as being mentioned both on the south and on the east coast, must, as already stated, be placed in the S.E. corner. But if Manapia was near the site of Wexford [Town], there would be little room for another tribe between the Manapii and the Brigantes. Therefore I should be inclined to place the Coriondi a little more inland, and perhaps we might regard Δοῠνον [Dunon] as representing their chief seat. This name probably represents the Celtic dun, a fort ... It might ... be the famous Dinn Righ on the Barrow below Leighlin Bridge. (Orpen 125)

Other scholars have similarly argued that the only way of accommodating the Koriondoi on the east coast, between the Brigantes and the Manapii is to move the Manapii further north into County Wicklow. This argument has been used to defend the claim that Manapia cannot after all have been in the vicinity of Wexford Town, but must have been much further north. Even Goddard Orpen eventually came to adopt this opinion.

I, however, would still like to identify Manapia with a trading emporium somewhere in the vicinity of Wexford Town, so the problem of squeezing the Koriondoi between the Brigantes and the Manapii is one which I too must face. Perhaps the solution is to take a leaf out of O’Rahilly’s book and identify the Koriondoi as the ancestors of the Benntraige and place them in an area roughly corresponding to the barony of Bantry [shaded on the map below]. This would leave room for the Brigantes to the south and for the Manapii to the east (with, perhaps, the River Slaney as the boundary between the two tribes). And if the Koriondoi’s territory stretched all the way to the mouth of the Slaney, they would qualify as a coastal tribe. Problem solved?

One of the advantages of this arrangement is that it keeps the Manapioi close to the Brigantes. Both Orpen and O’Rahilly speculated that the Manapii of Britain were neighbours of the Brigantes, and possibly even their subjects:

The name Manaw or Manann was not confined to the Isle of Man. It also survives in Clackmannan, and Slamannan in the neighbourhood of the Firth of Forth, where Ptolemy places the Otadini. The district south of the Forth was the Manaw of the Gododin of Welsh literature; and it is worth noting that this Manaw, like the district of the Irish Manapii, was coterminous with the territory of the Brigantes and probably subject to their rule. (Orpen 125)

If the Menapioi were a tributary tribe of the Brigantes, then it would make sense to find them settled next to the Brigantes in Ireland.

An Alternative Etymology

The contributors to the website Roman Era Names have also speculated on the etymology of the ethnonym Manapioi, but they have not accepted the scholarly consensus:

Μαναπια πολις (Manapia 2,2,8) was a settlement at Wexford of the Μαναπιοι, who were probably wetland people (as explained under Manavi) rather than part of a travelling *Menapii tribe. (Roman Era Names)

Following up that link to Manavi, we read:

The natural meaning of Manavi is something like ‘wetland people’, compounded from PIE *man- ‘man’ plus *ap- or *akwa- ‘water’. The water part is uncontroversial, especially with a river Avon running through this area, but Celticists are reluctant to interpret Man- as ‘man’, preferring ‘outstanding, prominent, high’ (James, 2014:2,268). Presumably this is because man/men developed particularly in Germanic languages (e.g. tribes such as Marcomanni) not in Welsh, and because bogtrotter became an unkind term for poor Irishmen. Perhaps the ‘prominent’ idea can be salvaged by arguing that raised mires naturally get higher over the centuries or that people in wet areas live on the high spots. On the other hand, the Man- part might mean ‘mean, common, shared’, from PIE *mei- ‘to trade’, focussing on lifestyle more than terrain. (Roman Era Names)

Nevertheless, they do concede a possible connection—albeit a purely semantic one—between the Irish Manapioi and the Belgic Menapii:

Related names appear to include the Menapii tribes around the mouth of the Rhine, the Μαναπιοι (Ptolemy 2,2,9) and Μαναπια (Ptolemy 2,2,8, at Wexford) in Ireland, and Monapia, the Isle of Man. Later survivals include Fermanagh and parts of Pembrokeshire (former Menevia and possibly Carn Menyn). All these areas had flourishing prehistoric populations and extensive bogs, which can be hard to see nowadays after centuries of drainage, peat cutting, and land “improvement”. It is unlikely that there was a single Menapian people who migrated en masse to all these areas. More likely, Ptolemy and others used a similar name for peoples with similar lifestyles and environments, but no close political or genetic relationships. (Roman Era Names)

Conclusion

Tentatively, I will continue to identify Manapia as a trading emporium somewhere near the mouth of the River Slaney in County Wexford—perhaps even on the site of the modern town of Wexford, although this lies on the right bank of the river. The local populace, Ptolemy’s Manapioi, probably occupied the territory on the left (eastern) bank of the river, with the Koriondoi on the opposite bank, and the Brigantes to the south of Wexford Harbour.

References

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Eoin MacNeill, Phases of Irish History, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1920)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, R P Pryne, Toronto (2015)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- John Rhys, The Early Irish Conquests of Wales and Dumnonia, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Volume 1, Number 8 (4th Quarter 1891), pp 642-657, RSAI, Dublin (1891)

- Whitley Stokes (editor & translator, The Tripartite Life of Patrick, Part 1, The Stationery Office, London (1887)

- Tigernach, Whitley Stokes (editor & translator), The Annals of Tigernach, in Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville (editor), Revue Celtique, Volume 16, Number 4 (October 1895), Émile Bouillon, Paris (1895)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- G H Orpen: © Royal Society of Antiquaries Ireland, Fair Use

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Possible Territories of the Brigantes, the Koriondoi and the Manapioi: Map Data © OpenStreetMap, Open Data Commons Open Database License

Excellent history and very nice article. Thank you For sharing with us...

Posted using Partiko Android

very nice historical post dear..love you so much...